Stories as Songs: Oral Traditions in the Khasi Hills

Renee Lulam

Renee Lulam lives in Shillong, a beautiful hill town in the northeast of India. She read comparative literature and has been collecting stories and narratives as an independent researcher and writer since about 2004. Renee is interested in how stories and narratives are used to connect with people and for healing, especially among small communities in the northeast of India. With Julius Basaiawmoit, Renee won a fellowship from Sarai-CSDS in 2007 to research and document the changing face of democratic spaces in urban cosmopolitan Shillong. Before that she was a Majlis Cultural Fellow, researching and collecting narratives of women from her region. Renee occasionally presents talks on the North Eastern Services of All India Radio.

renee75@gmail.com

STORIES AS SONGS: ORAL TRADITIONS IN THE KHASI HILLS

The year was 2008. I was collecting stories and narratives around the Khasi practice of erecting monoliths as markers to commemorate events, researching how these are an archive of memories for the community. The research was to turn into a documentary based on the stones around Mawrong and Raid Narlein in Ri Bhoi District of Meghalaya. I was co-director to Julius Basaiawmoit, who was also Sound Recordist and Sound Designer for the film. In the post production stages of the film, Chosterfield Khongwir agreed to join us as Music Director. Referred to as Babu Chos, an appellation of reverence, I was told to call him ‘Ma’, a more familiar term of respect reserved for closer associations.

Shillong, a beautiful hill town in the northeast of India

Shillong, a beautiful hill town in the northeast of India

Having grown up in Shillong, where for the longest time, All India Radio was the only source of music to many in this small hill town, Ma Chos’s name was not particularly new to me. AIR was where local artists aspired to perform, and where we listened to them. AIR’s mixed bag of artists included other local folk artists like Beriwell Kyndiah, Skendrowell Syiemlieh, Brektis Wanswett, Helen Giri, Lumtimai Syiemlieh on one side; and names like Headingson Ryntathiang, Phom Lyttan, The Fentones, Therisia War, The Vanguards and others who wrote, performed and sang in popular Western music genres on the other.

Chosterfield Khongwir is a noted composer, musician and ethnomusicologist; he was also a senior lecturer with the Khasi Department in St. Edmund’s College, a premier institute in Shillong from where he retired. He grew up in Umsning, Ri Bhoi district, forty-five minutes from Shillong, ‘A melting pot of Khasi culture . . . Khasis from everywhere, all districts live there.’ As we discussed narratives the stones yielded, Ma Chos would break in, sometimes to explain a reference or to clear some confusion, but mostly to hum a tune that traditionally would accompany a particular narrative. ‘You see, in Raid Narlein this song is sung this way,’ he said, breaking into a little tune. ‘Five kilometers from there, they sing the same song like this,’ and inserted a subtle slur to the tune that my untrained ear would have missed had he not pointed it out.

‘These slurs are only learnt by the ear,’ Meban had told me some weeks ago, on a hot spring afternoon in 2014, in Martin Luther Christian University’s Department of Music. Mebanlamphang Lyngdoh is another practitioner, a composer who also plays a variety of indigenous musical instruments. ‘These aspects of Khasi music cannot be put into staff notation; they have to be learnt by ear, transmitted orally.’ What about Tonic Sol-fa? ‘The Khasi music scale cannot be adequately rendered into tonic sol-fa either.’ In his thirties, he has been involved with several cultural organizations, and teaches in MLCU. Before this, he taught in the Music Department of St. Anthony’s College. Both institutes are in Shillong. He invited me to a programme at St. Mary’s School, ‘The HTCWO will hold a programme there. It is a part of the organisation’s efforts to sow an interest in traditional music in young minds.’ I wanted to know how they did that. ‘We carry instruments; we play them, we sing songs and tell stories about the songs, about the instruments. You can also meet Bah (another term of respect for men) Teibor, the president.’

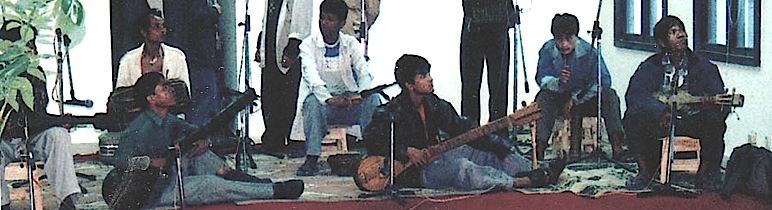

Introductions. Pynter Orchestra

Introductions. Pynter Orchestra

The first time I encountered HTCWO (Hynniew Trep Cultural Welfare Organisation) was at the one-off 1st North-East Documentary Film Festival, way back in 2005. As a side show, festival organizers (the now defunct Institute of Environmental Management and Social Development) arranged for an orchestra to play local tunes on folk instruments to entertain the guests at lunch. Pynter Orchestra from Pynnursla, a little over an hour’s drive further uphill from Shillong, was associated with HTCWO. The orchestra has come a long way since, and remains connected with HTCWO.

I was late and the programme had already begun when I got to St. Mary’s School. Performers onstage were dressed in a combination of traditional clothing and casual wear. Meban was on the duitara, a stringed instrument, while Melinda Kharsati was at the mic. Around them were other musicians on their instruments – another duitara, the bom (a kind of floor drum with a bassish timbre), two or three ksing(drums), and more percussion instruments. In the corner lay more instruments, more strings and some wind.

Pynter Orchestra. The instrument is called Maryngud

I understood better what Meban meant by telling stories. Their interaction with the students had a certain story-telling aspect to it, as suggestions and information imparted were turned into narratives. I couldn’t tell if this was deliberate, a conscious effort; if there was a specific methodology behind it. I had only witnessed such levels of interaction before in more informal settings and smaller groups. When I asked Meban about it later, he gave me a look both befuddled and pleased. I realized it was not contrived, that it was a practice they were not even conscious of. I found that immensely pleasing too.

Segueing easily from Khasi to English and back to Khasi, the afternoon’s programme consisted much of songs, old and new. Songs I grew up hearing on the radio, and songs from contemporary practitioners; stories behind the songs, and always an acknowledgement of the song’s composer. The song that Melinda performed as I arrived was a Meban composition. A green banner above the stage announced the organisation’s motto: Lada ia ki rukom bad dustur la jong ia klet bad jah, ning ap sa tang ia ka por ban jah ka jaidbynriew. (If tradition and culture are forgotten and lost, it will only be a question of time that a race or nation will disappear.)

Bah Teibor was a small dignified man, with neat salt and pepper hair and sharp-eyes. ‘We need to reawaken in our youth an interest in our own art and culture. It is only when we are rooted and understand our own that we can appreciate and respect other cultures.’ He said. ‘We do not discourage them from practicing certain things from other cultures. But even if they do, if they are clear about their own, they will never be shaken. We will not lose who we are.’ Onstage, Timmy Kharhujon brought out his guitar to sing a song he composed about forgotten values, fatherless children and environmental degradation. Bah Teibor explained, ‘The first thing for Khasis is nature. It is God’s gift. We are all created by God to live together. Without Mother Nature, we will not survive.’

Survival, the anxiety of being swamped out, is a constant subtext in any conversation on Khasi culture. I asked him if he believed that the Khasi culture of fifty years ago was the same as that of a hundred years ago. ‘No, of course not. We adapted to the changes, but we knew who we were.’

It is likely that this anxiety stemmed from the time of the missionaries. Those who converted were encouraged to renounce their ‘old ways’ which were disregarded as ‘pagan customs’ that were ‘backward’, and for the longest time, Khasi traditional music was rendered almost invisible. During the two World Wars, these hills were recuperation centers for hundreds of soldiers fighting on the Eastern Front. During the Second World War, Shillong became an R&R Camp for British and American troops fighting in the Burmese War. With rest and relaxation came entertainment, and Western music was naturally the main scene. There were parties, sing-a-longs, stage performances; western music was central to all these. A whole generation grew up on this culture where Khasi music took a back seat. Today, it isn’t just ‘Western culture’ that they are anxious about, but Bollywood culture as well. ‘Now, things are different because the kind of mixing that goes on now is different from the kind before.’ Bah Teibor continues. ‘Now also we must adapt. But we must be clear about our own so that we do not lose ourselves.’

Timmy is the vocalist of Snow White, a folk-influenced rock band which draws on local mythology in their lyrics, and sings in Khasi. Rangdajied – which can be literally translated to mean ‘the chosen one’, though it means much more in context, and highly symbolic in Khasi culture and mythology – was the title of their first album released around 2005, which in many ways remains seminal to this day. Recently, they discovered that a local commercial concern used one of the numbers in the album as a theme-song for one of their businesses without informing the band. ‘Talent and hard work are still not respected, what can I say?’ Timmy lamented. ‘We put so much into that album, that song. Especially Don (Lead-guitarist of the band and composer of the song). With just one click of a button, all that hard work is used for commercial gain. We would have preferred if it was a band performing the song without asking us.’ I remembered Pynter Orchestra at the film festival. There was little I could say; such undervaluing of artists and practitioners was discouraging. I had hoped things had improved.

Folk musicians still struggle for acknowledgement in the mainstream, but practitioners like Bah Kerios Wahlang have made headway after years of struggle, garnering modest recognition for his music. An accomplished musician and artisan from Mawngap village, he is an extraordinary presence at folk festivals across the country. Another presence is the much younger and lesser known Kong Battimai Kurkalang of Laitkyrhong village who took her music to the World Social Forum in Mumbai in 2004.

After the programme Meban was to head towards Lakreh School, where the Jeebon Roy Academy of Creative Arts conducted music classes in the evenings. ‘There are many institutes that teach our music,’ he said. ‘And there are also many who are learning. Even non-Khasis. Times have changed.’ Change was slow, not always visible, but it was there. ‘Previously, when you said Khasi folk music, people thought it was music practiced only by those of the indigenous religion. But now that has changed – anyone can be interested in folk music,’ Ma Chos had said years ago.

The orchestra preparing for a performance. The instruments that resemble the sitar are called the Marynthing.

The orchestra preparing for a performance. The instruments that resemble the sitar are called the Marynthing.

Schools like KJP Synod and Pearly Dew include folk music as an important extra-curricular activity. Pearly Dew Secondary School is situated in the middle of an otherwise residential locality of Jaiaw Laitdom. The school’s founder and Principal Ibarilin Kharsati started the school as a response to rising poverty and number of drop-outs in the community. The school has successively yielded better results at the State Board examinations. The Headmaster’s office is housed in an old Assam-type construction. It is large and airy with clean white-washed walls and black wooden panels. Musical instruments like the ksing, the duitara, and some guitars lie in various corners and on shelves. On informing the office-staff, students are allowed to take any of the instruments out of the office, to be returned before the school-day ends. Various members of Summersalt, a gospel-influenced band, who include traditional instruments in their music, went to this school. The band features a number of innovations in their repertoire, experimenting with common items found around a Khasi household, like brooms and baskets as instruments.

One street down from Pearly Dew School is the home of Lumtimai Syiemlieh. Kong Lum (‘Kong’ is a term of respect reserved for women) has been an All India Radio artist since her youth, and the youngest daughter of Kong Listrimai Syiemlieh, arguably one of the most prolific of Khasi composers, and foremost among the women. I had gone to meet her in the summer of 2007. She lived in one of those old Shillong houses: small, neat Assam-type with a corrugated tin roof and rain gutters. The garden in her front yard was a burst of cheerful colours.

A young Kong Lum performing.

A young Kong Lum performing.

Kong Lum comes bustling to the door. She has a ready smile and a girlish giggle. Everything about her draws one in. In Khasi matrilineal practice, being the youngest daughter makes Kong Lum primary custodian of the family’s heritage. She takes this seriously. ‘We are five brothers and three sisters, and most of us used to sing. Four of my brothers have passed on. My mother composed songs and arranged them. She taught us about singing and music,’ she said, offering me some kwai (areca-nut with betel leaf and a dab of lime) from the shang kwai – a basket where the makings of kwai are kept. Usually, each Khasi household has one of these. ‘My children are also blessed to have spent their formative years under her guidance. They were both already performing at All India Radio at three, four years of age. After she passed away, I continued to teach them music. They should know how to sing their grandmother’s compositions.’ Kong Listrimai composed songs about Khasi life, Khasi values, the Khasi worldview. ‘But my favourite are the ones about the love of a mother, a mother’s heart,’ she continued, ‘a mother’s love is the hearth of the family ‘rympei’; it is the source of life, warmth, and wealth of a family. I don’t mean “money” wealth.’

This symbolism of the hearth as a mother’s heart is aptly illustrated in the lyrics of ‘Rympei Baieit i Mei’, roughly translated to mean ‘Beloved Hearth of Mother’. The hearth represents nurture, value, instruction and wise counsel. ‘Even courtships took place around the hearth, under the watchful eye of the mother,’ Kong Lum explained. The song’s opening lines Rympei baieit i mei/Ba sngewhun ha ka pyrthei/ La duk la thngan te lei/Ba don ha jan i mei/tang jynhaw jong i la biang, talk about the power of a mother’s love to bring contentment to her children’s world, poverty has no place close to a mother’s hearth. The mere sound of her voice is enough reminder of one’s wealth. Another verse goes Rympei baieit i mei/ba sngewshain ha ka pyrthei/khyllait na ieing I mei/ngan iaid sawdong pyrthei/tip kan long kumno ia nga?, declares it is at the mother’s hearth that faith in one’s self is formed. One could leave the home and travel the world, but the question is what would happen without the hearth – the faith in one’s self to leave the home and travel the world would not be, if not for the hearth. It also is a call to never forget all that was imparted at the hearth.

Kong Lum testing the acoustics of a studio!

‘My favourite are the songs where she talks about love between a man and a woman. Romantic love,’ Kong Cass pitched in. Kong Cassandra Syiemlieh is Kong Listrimai’s second daughter and Komg Lum’s elder sister, who dropped in earlier to visit her sister. ‘You see, in our matrilineal system, it is very important to understand this relationship. If we don’t understand it, we will not understand the responsibility of men. These days, only few men grasp the importance of their position in our society. Many young boys don’t even know,’ she said. Kong Cass retired as Senior Lecturer of English from St. Edmund’s College. She did her MPhil research on Bob Dylan. Their eldest sister who also used to sing, Kong Loissimai Syiemlieh, was out of town, visiting relatives in Mairang, West Khasi Hills district, where Kong Listrimai was originally from.

Kong Lum’s sons both sing and play various instruments. ‘But Arbanjop, my younger son prefers playing instruments to singing. He opted to study for a Bachelor of Music degree. He also paints. Lamphang, the older one loves singing. I have trained him in traditional Khasi and folk; he has also learnt jazz from Pauline (Warjri – voice artist, musician and director of Aroha Choir), and now he sings both,’ she said with pride when I met her at a concert early last year.

Indeed, Lamphang Syiemlieh has made something of a name for himself as a growing artist whose range and style are inimitable. When I met him this February, Lamphang himself said, ‘I love jazz and I will continue to sing it, but I will always sing Khasi traditional. Especially my grandmother’s songs. How can I forget what she and my mother taught me? That’s my heritage.’ Like Meban had said, there are some things about traditional music that can only be transmitted and taught orally.

What advantage do the music schools offer, then? Schools like Dr. Helen Giri’s La Riti Academy, Snap Paka Institute and others enroll a number of students, but how does formal learning benefit them the way oral learning does not? ‘A theoretical learning of music; they learn how to read notes, and once they understand theory, they have a strong foundation in their art,’ said Meban, as he and the others packed-up their instruments at the end of the programme. Doesn’t rendering folk songs into notes interfere with the innovative spirit of folk traditions, I asked. ‘What they are taught is to read music and the basic tune of a song. We encourage all our students to express themselves through the songs, to be creative with them. They are encouraged to innovate. And as I already said, there are still things that can only be learnt by the ear.’

I could understand that. Community life isn’t what it used to be, and these arts that were once taken for granted can no longer be; oral practices also have to adapt. ‘One thing you must not forget, culture is dynamic.’ Ma Chos had said, ‘it has to be dynamic for us to grow and survive; if culture is no more dynamic, we cannot adapt. That is very dangerous for our survival.’

Lamphang Syiemlieh

‘We have to innovate even with our instruments,’ Meban continued on the topic. ‘With the duitara, while you see wooden pegs in front, we use tuning keys from the guitar behind. We have to; with wood, it soon becomes useless – wood shrinks when it dries, and that loosens it.’ I wondered aloud how that was avoided in olden times. ‘I think it is because in olden days, the duitara was used only in one place, around the hearth. They would leave it near the hearth, and they played it near the hearth – maybe two, three songs. See, performance itself has changed and evolved. Now we have to play ten songs before a large audience in a hall. The instruments also have to be made to last through these rigours,’ he responded.

‘Performance taken out of the home and communities has helped us to understand our music better. The same song will sound different sung by someone from West Khasi Hills than from East Khasi Hills or Ri Bhoi. The tune would be the same, but it will sound different. You know, we wouldn’t have understood these things if performance hadn’t been taken out of the home to large audiences,’ Kong Lum said recently, as we chatted over red tea in her little kitchen. As she said this, I realized how similar yet vastly different Kerios Wahlang and Chosterfield Khongwir’s styles are. While roughly of the same generation, both singing in Khasi folk genres, to me the music of Ma Chos evokes an undulating landscape, gentle green slopes, and low-lying paddy fields, while Bah Kerios conjures a slightly more rugged landscape, waterfalls, vegetable plantations on hillsides, and cold mornings.

The programme wrapped up, Meban and I walked towards his car. He was already late for his next class, and I didn’t want to delay him further. He had been patient and gracious with my questions, as had Bah Teibor. It had been a lovely afternoon, and I learned much. I thanked them as they got into the car. They would have to drive downhill on Bomfyle Road, then up past the Governor’s House, and cut across the always crowded Police Bazaar before they reached Umsohsun, where Lakreh School was.

As I crossed Laitumkhrah’s busy traffic laden Main Road on foot, heading downhill towards the more residential part of the locality, where I live, I suddenly longed to hear Ma Chos’ voice. It had been far too long. I dialed his number from my cell-phone. He told me how occupied he was, that after retirement he was even busier. He sounded content. ‘I have also started a music school in Umsning. It’s good that you called and now we are reconnected. We’ll meet; I will call you when I come to Laitumkhrah. I must go now,’ he ended.

I smiled, happy to hear he was even more immersed in music in retirement. I look forward to the call.

Renee Lulam

Shillong

27th April 2014

Here are two songs by Chosterfield Khongwir. Both songs were recorded and mixed by Julius Basaiawmoit for Renee and Julius’ film Ki Sakhi Ka Mynnor.

Related Links

Lamphang singing a song composed by his grandmother : https://soundcloud.com/lamphang-syiemlieh/iam-meikha-from-the-album

Aroha at the Healing Histories conference, Caux, Switzerland: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0_VmFlnLrkk

- Travelling alone, but not quite

- Moving with the Song: Loss and Longing in the Migrations of Bengal

- Songs from a Tide-Swept Land

- Sonic Symphony

- Art East: Eastern India’s stories of Partition

- শ্রবণ

- মনসামঙ্গল ও একটি এটলাস ছাতার গল্প

- Man with a Recording Machine: Arnold Bake in Bengal

- Images of Listening

- Madly in Love: On a Trail of Songs of Separation

- শাহ আবদুল করিমের ভাব ও অভাবের গান

- I Hear the Drums Roll: Lessons in the Art of Listening

- In Search of Meaning: Reflections on Folklore

- BF Shelton and Oh Molly Dear

- ‘Accuse’ কাকে করবো?

- দ্য ট্র্যাভেলিং আর্কাইভ: শ্রবণ, স্মৃতি আর সময়ের গল্প