Ambikapur, Faridpur, Bangladesh. 31 March 2008. Jainuddin Boyati and team

Shahidnamar Jari

We had this session in the courtyard of our late friend, Sadek Ali’s house in Ambikapur bazar, Faridpur. The evening before we had had another session inside his house. Like his mentor, the poet Jasimuddin, Sadek Ali bhai was a true lover of music, which is why he could open his doors to anyone who came to him, for or with music, anytime of the day or night.

Our first experience of jari, a form of narrative folk song of Bengal based mainly on stories of the Battle of Karbala, was in 2006. Looking back now, however, I feel that at that time the significance of the form, its content and history, and its beauty, had passed us by. Jari is derived from Iranian azadari , the ritual of lamentation (from the Arabic aza and Persian dari). The day we had gone on a boat to record music on the Kumar river, Sadek Ali had sung an abridged version of the Hanifar jari, also known as the Khatnamar jari, or Chacha-Bhatijar jari. It is the story of Hussain’s son Joynal (Zainul Abedin) sending a letter to his chacha (uncle) to save him from the tyranny of Ejid (Yazid) after the death of his father in the Battle of Karbala. The previous day we had had a recording session in Sadek Ali’s house, and Nuru Pagla had sung another version of this same jari, although Nuru had mistakenly called it the Shohidnamar jari. But none of this had struck us then. It is only with repeated visits and replays of the recordings from those sessions, that we have been able to go beyond Ibrahim Boyati’s bichchhed or Idris Majhi’s bhatiyali, which had seemed like the main gifts of those 2006 sessions. It took several years to realize that that trip had opened up for us the possibility of new journeys into yet uncharted songlands.

As in many other cultures, in Bengal too it is common to sing long and short narratives or to tell stories through songs. Jari, kobigaan, palla gaan, kirtan, agomoni, panchali, punthi, goshtho are all different forms of narrative song, based mostly on Hindu or Islamic mythologies. In some of these forms, the way of telling the story is through a chronological ordering of events with plot and subplot and moral preaching. In some the storytelling is more argumentative. These are communal songs; that is to say, they are songs of the community. The audience and performer are bound together in the telling—rather, re-telling —of tales that they both know. Thus, between the listener and the storyteller/singer, a kind of re-enactment of the rituals of performance takes place; the audience also becomes the performer, often clapping the rhythm and singing the refrain and responding with various gestures and sounds of exclamation, appreciation and lamentation, as the story and its form demand.

Jainuddin Boyati and team

In her book Jarigan: Muslim Epic Songs of Bangladesh, Mary Frances Dunham writes about how the jari provides entertainment, as well as educates. Dunham, an American, worked with the folk poet Jasimuddin on his Jarigan anthology in the late 1960s when she was staying in Bangladesh. She came back after about twenty years to independently follow up on her work and create a book and audio collection of field recordings out of her research. Her recordings and papers from that time are being archived at Columbia University.

http://findingaids.cul.columbia.edu/ead/nnc-rb/ldpd_10666979/summary.

The jari and other narrative songs return us to our mythologies while reinforcing the place of these stories in our lives. Some myths are interpreted to have local and personal meaning, such as we see at the time of the Durga puja in Bengal, when Durga is invoked both as the slayer of evil as well as the daughter visiting her natal home, soon to return to her husband. Some myths such as the Manasamangal or Bonbibir Pala have immediate relevance for people who live in close proximity with nature; they are thus infused with local ecological and anthropological meaning. Some myths have wider political purpose, such as consolidating communities through the singing of the story of Karbala. Every year Hussain and his clan must die in the Battle of Karbala in order for the community to come together. However, this is only part of the story. Why we need our myths, why we need our occasions to come together in celebration or lamentation cannot be explained with one reason. Just as Durga’s homecoming has political, economic and commercial meanings too, similarly when in jarigan the grief of Fatema is sung, it becomes the grief of every mother; Joynal’s fear is the fear of any child.

Within living traditions, familiarity is a pre-condition for appreciation. And familiarity here means not only knowing the story, but also knowing the form and the protocol of performance. Even as audience you should know when and where you can come in. How to acquire such familiarity? Not just for jari, the question comes up when we are working with other forms too; say with Amulya Kumar’s jhumur which demands a detailed foreknowledge of the Mahabharata. Or baulgan, where you are expected to understand all the play of words and cosmogonic riddles. Here we are talking about the familiarity of the insider in any community, of belonging to a tradition. Standing on the edge of communities and traditions, we often find ourselves asking the question: what is our tradition then?

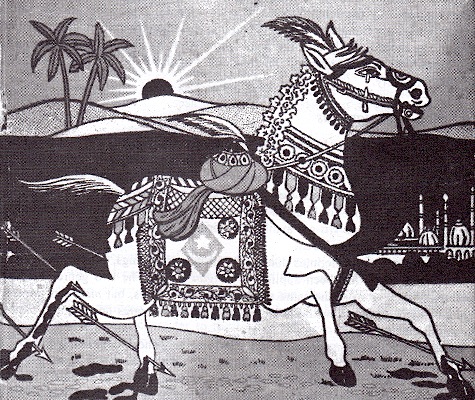

Duldul on the cover of Mir Mosharraf Hosein’s Bishad Sindhu. Image taken from Mary Frances Dunham’s book

Arnold Bake had recorded a group of jari singers from Mymensingh (Maimensingh, according to Bake’s notes) in the east of what is now Bangladesh, at an annual event called Suri mela in Birbhum in the west, on 23 February 1932. This troupe had been brought to perform in Kolkata and Birbhum by the song collector and district adminitrator, Gurusaday Dutta. Jasimuddin, also writes about this performance of the Mymensingh jari singers in Kolkata in the introduction to his anthology of jarigan. According to Jasimuddin, Dutta had also filmed the performance; but where that film might be now, is not known. Could it be that Jasimuddin was referring to Arnold Bake’ footage, because Bake did have a camera with him on that visit and there were films from Kenduli and elsewhere, which can be seen at the British Library and ARCE? So far in our research we have not spotted any Jari film in the Bake collection, however. Jasimuddin’s own collection becomes for us a very useful guide book, allowing us to enter this world of the narrative song through his written text. We need our written records of orality in order to access the world of the oral.

Our location as the outsider-listener has its advantages tool. Questions come to our minds precisely because we do not belong. In our work, through our act of recording we have been trying to understand the social and historical processes that lead to the birth and death of traditions. Why is it that the jari is no longer sung as a living tradition in parts of Bengal like it used to be in the time of Jasumuddin? The jari utsab in Gafforgonj in Mymensing—is that a continuation of the old tradition that Gurusaday Dutta and Arnold Bake had recorded or is it the ‘festivalisation’ of an otherwise ended tradition? The marsiya that the mostly non-Bengali Shia community of Bengal sings in the month of Muharram—does it have any connection with the jari of Bengal?

Writer, teacher and gender studies scholar Epsita Halder has been researching the marsiya tradition of Bengal for some years. She makes her own observation about the differences between jari and marsiya: ‘While ritualistic mourning over the death of Imam Husayn, the grandson of Prophet Muhammad, and his companions in the battle of Karbala entered the domain of folk repertoire in the form of the Jari, it also remained an integral part of the Muharram ritualistic tradition. The performative aspects of Jari include a fluid and undesignated audience, whereas majlis associated with the marsiya tradition is performed in the exclusive and sacred realm of the ritual, to commemorate the martyrs of Karbala in the month of Muharram. The space of ritualistic-performance and the sacred time of performance at the majlises are ritualistically fixed under the parameters of Shi’i religiosity.’ (Private communication with The Traveling Archive. See also Epsita’s essay in Baul Fakir Utsav journal 2013 )

Epsita’s noha video. Shot in Kolkata

The ‘fluidity’ that marks the jari performance can transform the courtyard of Sadek Ali’s house in Uttar Shobharampur into the battlefield of Karbala. Nuru Pagla runs around wildly making up his version of the Hanifar jari. Joynal Joynal, he cries, lamenting the helplessness of the child whose father has died in the Battle of Karbala. Sadek Ali, the well-off trader of Faridpur, is a warm and generous host and householder. His college-going girls, one married daughter, little grandchild and his equally generous wife all sit around the performers on this day of singing in January 2006. But deep inside, Sadek Ali and his wife are crying for their lost son, who lies in his grave in the garden of their house, to our right, shaded by the pomegranate tree. Who is the Joynal in Sadek Ali’s story? Sadek Ali himself, or his son? Who is more helpless? The next day on the Kumar, Sadek Ali sang this same song: একটা পুত্র দে রে আল্লা, একটা পুত্র দে/কামাই খাইবার সাধ নাই, মইলে মাটি দিবে কে? Give a son, Allah, give me my son/ I don’t care for riches in life, but who will bury me when I die? The chorus of listener-performers joined him in lament.

Some day I hope that we will also be able to join this singer-listener community. It must be comforting to have a place or a song to call one’s own.

Sadek Ali had moved to his other house in Ambikapur in 2008, when we went for this recording session. We asked him and our friend Salamot bhai if it would be possible to record a fuller session of jari. They said it was not easy to find jari singers anymore, because jari as a form was slowly fading out from their region. Jarigan flourished during a time of leisure, with feudal patronage. Now the times are changed. However, despite the changing times, a team could still be gathered. Salamot bhai went to the house of Jainuddin Boyati in the Lokkhipur neighbourhood of Faridpur and Jainuddin Boyati in turn got together his brothers Halim, Mofajjal and Alim; Adom was another relative. Mofajjal, who had a piercing voice, also played the dhol. Adom and Samir Kumar Saha played the flute, Mukul Kumar Shil played the harmonium. They sang almost the whole of the Shahidnamar jari. You could hear strains of other musics in their song, suggesting musical journeys and interweave of forms—of the panchali, kirtan and bhatiyali. It was getting late in Sadek Ali’s courtyard. When they finished they said, now only Yazid remains to die. বাকি রইল এজিদের মৃত্যু।

Written in May, 2014

Related links:

Jarigan in Sunamganj. Note similarity with Manasar gaan.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Q-gQ6u0ceWY#t=100

Jasim criticism of Abbasuddin

https://web.archive.org/web/20150317233959/http://banglamusic.com/reviews/jasimuddins-criticism-of-abbasuddin-3.html

Jasimuddin and Alan Lomax

http://sos-arsenic.net/lovingbengal/news.html#30

The ‘western’ tradition of singing Marsiya, very different from the tradition of jari

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Zcm-QB922aE

- Saptiguri, North Bengal. 27 November 2003. Nirmala Roy

- Bolpur, Birbhum. 25 November 2003. Nimai Chand Baul

- Kolkata. 4 September 2019. Purnadas on Nabani Das Baul

- Surma News Office, Quaker Street, East London. 27 February 2007. Ahmed Moyez

- Ambikapur, Faridpur, Bangladesh. 29 April 2006. Hajera Bibi

- Sylhet, Bangladesh. 22 April 2006. Chandrabati Roy Barman and Sushoma Das

- Sylhet, Bangladesh. 21 April 2006. Arkum Shah Mazar

- Sylhet, Bangladesh. 20-21 April 2006. Ruhi Thakur and others

- Jahajpur, Purulia. 27 February 2006. Naren Hansda and others

- Faridpur, Bangladesh. 24 January 2006. Binoy Nath

- Uttar Shobharampur, Faridpur, Bangladesh. 22 January 2006. Ibrahim Boyati

- Baotipara, Faridpur, Bangladesh. 21 January 2006. Kusumbala Mondal and others

- Kumar Nodi, Faridpur, Bangladesh. 21 January 2006. Idris Majhi and Sadek Ali

- Debicharan, Rangpur, Bangladesh 18 January 2006 Anurupa Roy & Mini Roy, Shopon Das

- Mahiganj, Rangpur, Bangladesh. 17 January 2006. Biswanath Mahanta & Digen Roy

- Chitarpur, Kotshila, Purulia. 28 November 2005. Musurabala

- Krishnai, Goalpara, Assam. 30 August 2005. Rahima Kolita

- Chandrapur,Cachar. 28 August 2005. Janmashtami

- Silchar, 25 August 2005, Barindra Das

- Kenduli,Birbhum. 14 January 2005. Fulmala Dasi

- Kenduli, Birbhum. 13 January 2005. Ashalata Mandal

- Shaspur, Birbhum. 8 January 2005. Golam Shah and sons Salam and Jamir

- Bhaddi, Purulia. 6 January 2005. Amulya Kumar, Hari Kumar

- Srimangal, Sylhet. 27 December 2004. Tea garden singers

- Sylhet, Bangladesh. 26 December 2004. Abdul Hamid

- Dhaka, Bangladesh. 24 December 2004. Ali Akbar

- Dhaka, Bangladesh. 23 December 2004. Monjila

- Changrabandha, Coochbehar. 16 December 2004. Abhay Roy

- Santiniketan, Birbhum 27 Nov 2004 Debdas Baul, Nandarani

- Tarapith, Birbhum. 14 October 2004. Kanai Das Baul