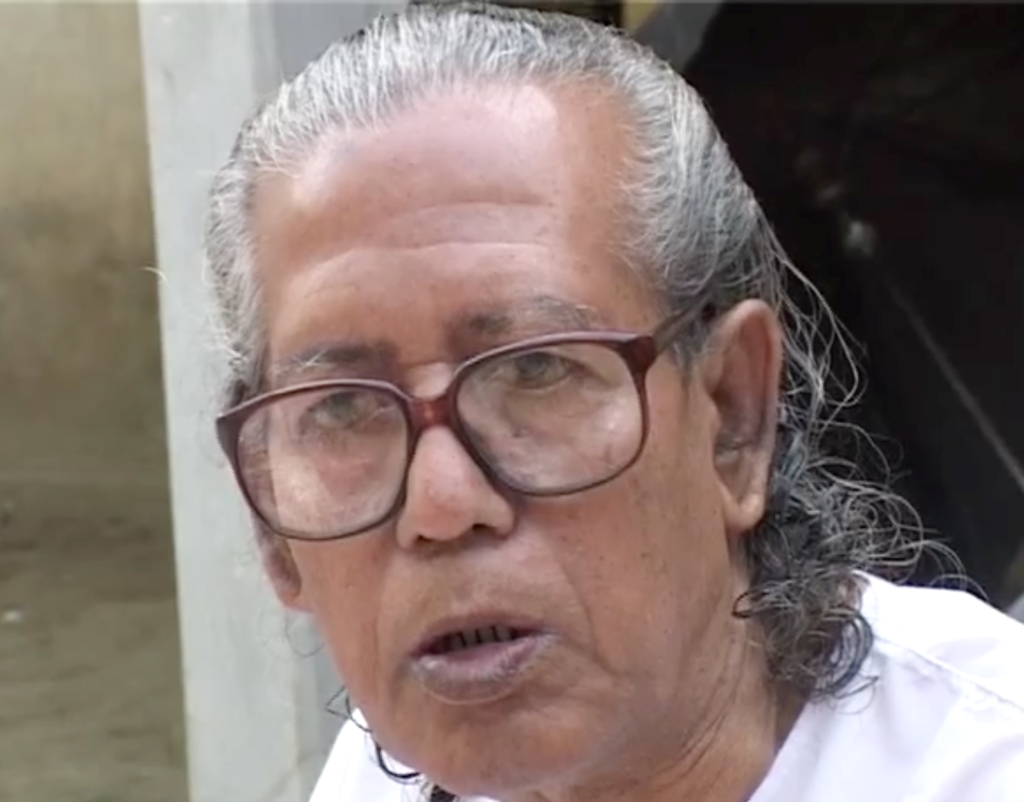

Listening through Haresuzzaman Hares

In 2019, I went to meet Haresuzzaman Hares, folk song and folk art and craft collector from Kishoreganj, whose father was the famous collector Mohammad Saidur, (1940-2007), to talk about jarigan and puthi-path of the Mymensingh-Kishoreganj-Netrokona area. These are places from where the prisoners of war of our story and our sailors and our jarigan singers all came, those recorded by Bake or even earlier by Wilhelm Doegen, between 1917/18 and 1934.We met at the Liberation War Museum in Dhaka, where Haresbhai worked. He has promised to take me to record the women who sing the Ramayan in his region.

Mohammad Saidur (1940-2007), collector of punthi, kantha, scrolls, clay things, as well as songs and stories, who also worked with Henry Glassie.

I stayed in touch with him and the next year, in the middle of the pandemic and at the close of my doctoral research, I called him several times to talk about this and that. We did not get very far in our search through these conversations, but the quality of these recordings reveals something unique about this research and I want to keep records of our conversation, because of that special touch that Haresbhai brought to it. A research is not always about results. If we are going round and round in circles, then we should talk about that too. These conversations show something about that process of this research.

In 2019 we had talked about going in search of Imam Bux Boyati’s descendants and finding old recordings of Imam Bux’s voice . Haresbhai had said that day that his father might have also made some recordings and they might be with Bangla Academy, Dhaka. He was not sure. I have this above recording on the Imam Bux sub-chapter of Santiniketan and Others, but I am keeping it here again, to show how a continuity built up in our communication.

When it came to working on Keramat Ali’s voice. I called Haresbhai from my home in Kolkata. Here are recordings of four pieces of telephonic conversations we had between July and September 2020. Being the son of Mohammed Saidur, Haresbhai has grown up in a tradition of listening, collecting and recording. I gave him the words of the puthi, as transcribed by Ali Ahsan, and he took them to many puthikars and boyatis (folk musicians) of the Mymensingh-Kishoreganj region, but they have not yet been able to identify the text.

‘I have talked with many of them, they have different opinions [bhinno mot]. Rahamat Ali Boyati of Hossainpur (80), said it might be Shahi Modina, an old puthi, but I have not heard of such a book. Then Lal Mahmud had said it could be the Taale Modina, but I don’t know that one either. We have to find the original book. They are illiterate poets [nirokkhor kobi], you see, but they have the song in them [shur ase] and will sing out the words, but they can’t read and that is the problem’.

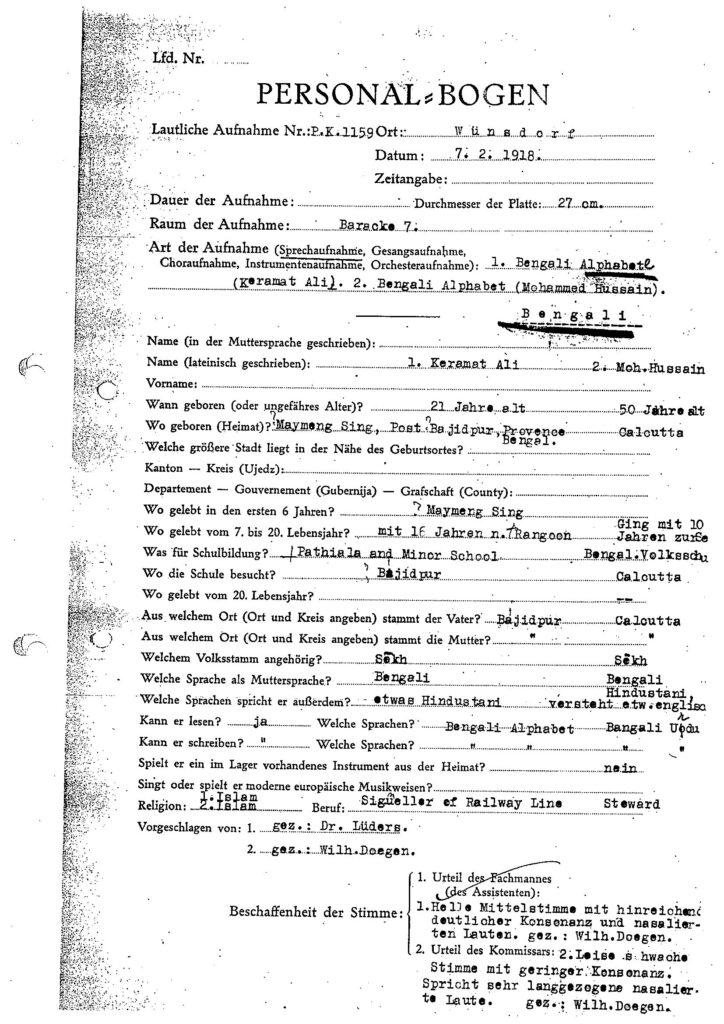

This is the personal information sheet for Keramat Ali Image courtesy Britta Lange

Haresuzzaman Hares told me that the main problem was that these singers were nirokkhor kobi, they were unlettered poets. But, Keramat Ali wasn’t nirokkhor, he could read and write, he went to pathshala and minor school. We know this from his Personal-Bogen.