Naogaon 4. October 2019

On 9 October 2019, I set out for Rajshahi again, this time with the intention of finally reaching the village named in Arnold Bake’s note for his Naogaon recordings: ‘Kunij gram; p. o. Kampur or Darilpur. Naogaon subdivision p.o. Soregachi’. I went by train from Sealdah to the Gede border, crossed to the other side, took a van rickshaw to the bus stand where a friend from Faridpur, Sanjay, whom I had met for the first time all the way back in 2006 said he would come and meet me. And then we took a bus to Kushtia. (You will find Sanjay’s mention here, even though he was with us on our trip to Fulsuti and Baotipara in Faridpur earlier that year)

Over the years, from my home, house no. 26H, to the border, be it Benapole or Gede, has become an easy train ride. Sometimes, though rarely, I have also hired a car. But this one was by train. I watched and listened to the fields and faces with both my eyes and ears as well as with the camera on my phone.

Once on the other side, I feel such a sense of homecoming that I must take it all in to my fill. It starts with the sky.

Then, cake and tea, and shop signs and street sellers open up a world that speaks to me in many time signatures. Sadhana Ayurvedics or what remains of that hundred-year-old pharmaceutical company ; the medicine seller on the street who makes me think of our favourite singer Ibrahim Boyati and how he had started life in music as a ‘canvasser’ or one who gathers buyers by the power of his voice and songs.

I met Nazrul Fakir in Kushtia. Nazrul, whom we have known for a long time, a very gentle creature, of whom Salamot Bhai, my dear departed friend and teacher in Faridpur, had said that he had the makings of a true fakir. I suppose it is because I was searching for some elusive fakirs with unfixed homes, that it felt as if there were footsteps of past walkers and seekers in every corner of this land–in Kushtia, Joshor, Naogaon, Mahasthangarh and everywhere I went. Nazrul took me to Lalon Sai’s mazaar, and there was singing going on there. Just regular singing, everyday things, and you knew how this was all part of the same world of sound. The sound from which Khoda Baksha Sai came and the sound of Nazrul too; something of that sound was in the recordings of Arnold Bake. These travelling musicians he recorded might have sung here in Kushtia, they might have come to Lalon’s urs.

I had my recorder open and was just walking through the place, and it was listening and recording, like I was doing with my ears and my mind. I don’t know who was singing, I did not try to know the name.

Nazrul Fakir, 9 October 2019.

From Kushtia I would have to go to Amdanga and then take a train to Rajshahi. But before that, outside the shrine of Lalon Fakir in Kushtia, there was a man selling a balm for every kind of bodily pain. And he was most concerned for the downtrodden, the ones who worked in the field and in factories, for the krishak and sramik bhai. For the hapless proletariat, Shanti Natural Pain Out!

There was still light in the sky when we reached Amdanga. Sanjay would go in the opposite direction, back to Faridpur. My train chugged along, it went over the Paksey Bridge and then someone mentioned the nuclear power plant in Rooppur and I pricked my ears. By now it was dark and the lights of ‘development’ shone in the passing landscape.

On 10 October 2019, with my usual companion on my Naogaon trips. folklorist Uday Shanker Biswas of Rajshahi University, and his friend and colleague in the Bangla department, Shoikat Arefin, who was with us last year too, we took the same rail route from Rajshahi, via Abdulpur, going along the Chalan Beel, to reach Kunuj, written as Kunij gram in Arnold Bake’s notes for the Naogaon singers. Diljan Fakir was supposed to have come from here.

Chalan Beel 2019

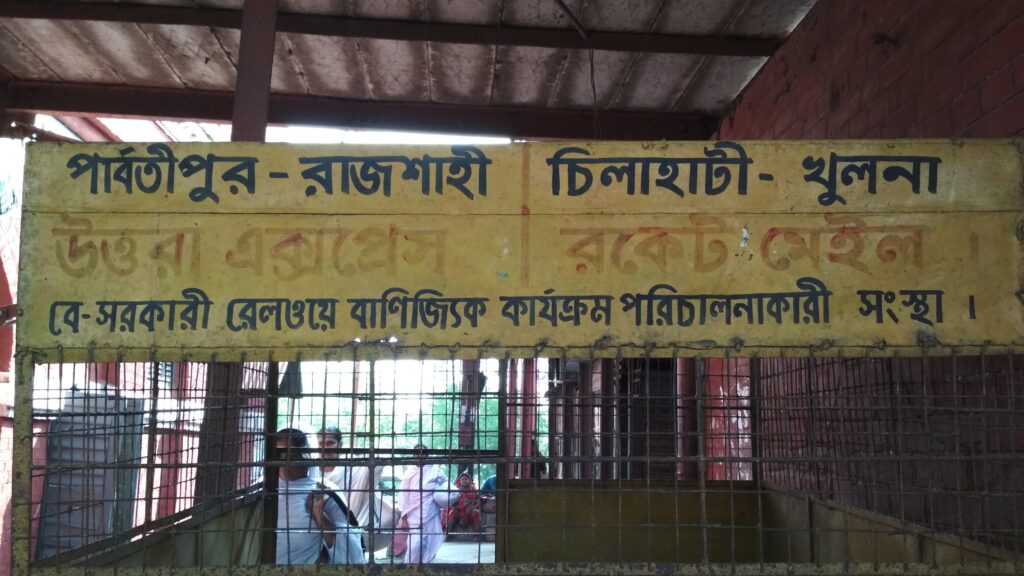

On the last trip the previous year, we had gone as far as Shailagachi—Soregachi in Bake’s notes—and learned that Kunuj and Dariapur (not Darilpur, as Bake wrote) were more or less adjacent villages. This time we got off at Santahar station and took a CNG (three-wheeler) to Kunuj. Uday, who knows these parts like the palm of his hand was showing me things at the station that were also signs of a simultaneously erased, memorialised, forgotten and excavated history.

Following the same rituals like last time. Same route, same people, same food, same seeing, same listening. I think rituals (sometimes invented) and repetitions have been a trope in my work.

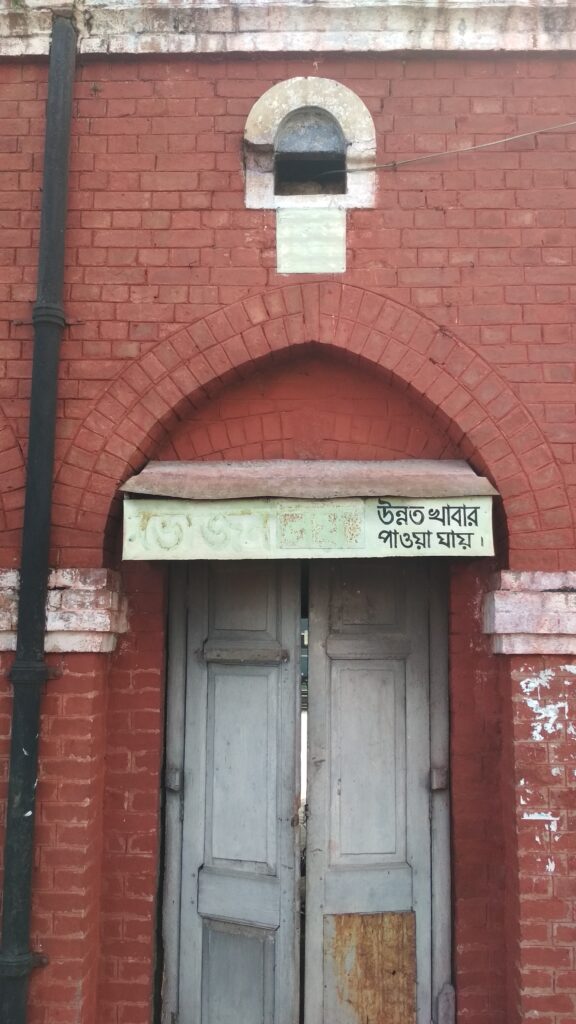

Santahar station is old and has its own history, and it wears that nineteenth century look in part. Interestingly, there used to be two separate canteens, one for Musalmans and one for Hindus. The sign Hindu Bhojanalay has been whitewashed now since the times have changed, the demography has changed, gradually since Partition in 1947.

Anyway, finally we reached Kunuj, under Raninagar police station. Raninagar is where we had gone on our very first Naogaon trip, with friend Tapas Majumdar, a banker in Rajshahi. Sukanta Majumdar was part of that journey. Then we had gone to a tea stall by the station in Raninagar, because those are places where you get to meet people. No one appeared to know then about where we could find the fakirs, or the songs. From that trip to now, we had come some way.

Photos: The Travelling Archive, 2015

Since the name Kunij gram was written on Bake’s notes against the name of Diljan Fakir, we specifically asked about him at the grocer’s after reaching Kunuj. Do you know of a man named Diljan Fakir who lived here a long time ago? A crowd gathered. A man by the name of Abdur sat with us in an empty shack opposite the grocer’s, listening to our story. He then said that Diljan (I am not sure if he said Diljan or Dilchan) Fakir was his father, who had died an old man in the 1990s. That kind of matched the time we were looking for. He said that there were many singers in this entire area. It was a strange moment of revelation, yet there was also a level of disinterestedness on Abdur’s part. He did not want to listen to the song of his father; he was more worried for the fish in his basket, which he would have to sell before it got late. He promised to come and meet us later, but I somehow knew he couldn’t come and I was right.

With Diljan Fakir’s son, Abdur, in Kunuj. 2019.

All these recordings and images are made with my camera and Zoom H2N recorder

Other people had gathered around us, including a very lively woman. Her name was Aklima and she was also a singer, she said. They heard the names on my Naogaon list and told us we should go to Dariapur, the next village, and meet Mukunda Fakir’s grandson, Mohammad Shamser Fakir. Mukunda Fakir was on Bake Cylinder No. 85, Diljan is 87. Suddenly things were happening so fast that it felt unreal. Meanwhile Abdur, who had identified Diljan Fakir as his father, had left and Aklima led the way to Dariapur, to Mohammad Shamser Fakir’s house. The man looked like a fakir, with his long wavy hair and a calm face. People had already gathered in his room. Uday, Shaikot, and I took turns to tell them the story of Bake’s Naogaon recordings. This is a village of singers, Shamser Fakir said. It’s traditionally been this way. He recognised almost all the names on Bake’s list. Not the ganja workmen; they might have been just labourers who worked in the ganja plantation, not fakirs. As a boy Shamser Fakir used to hang around with Basiruddin Fakir, of Cylinder No. 86. Nasiruddin was his brother — the name won’t be Masiruddin, he corrected me. Nasir, Basir, Tasir — they were brothers. Then Diljan (chand?), Tiljan …

Now everything was becoming absolutely clear to me. When Bake had asked where they were from, they must have said something like, ‘Kunuj, Shailagachi, Dariapur—but it’s all the same. We are all from the same place.’ The description for Masiruddin Fakir on the Berlin archive’s Naogaon list was ‘Sänger einer religiösen Bruderschaft,’ singer of a religious brotherhood. This then was that brotherhood — they were all part of it! ‘Fakirer daria’, Shamser Fakir said. ‘We have many fakirs here, almost like a daria, a flowing river; which is why the place is called Dariapur’.

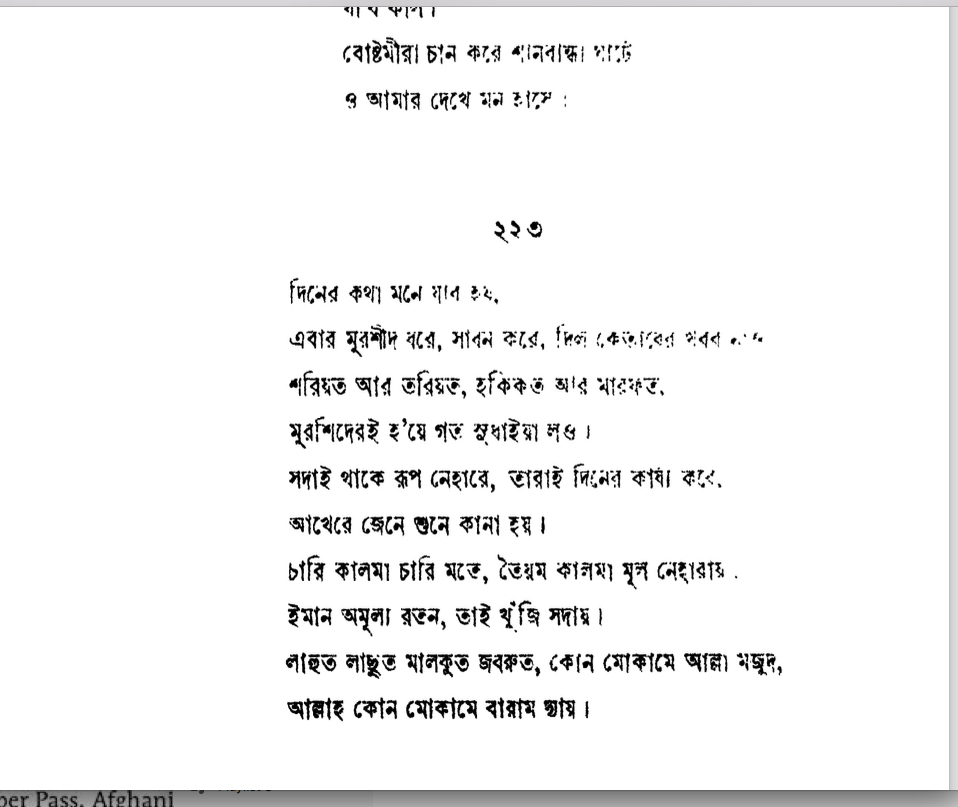

I took out my laptop; I had my portable speaker with me this time, so that I could amplify the sound . I played the recording on the first cylinder. This was the song, ‘Amar kotha moner jaoa hoi.’ The cylinder started to roll, the gyrating noise began. The first two words were gobbled up by that sound of the machine. The song started from the third word, ‘mone’. Shamser Fakir said: Diner katha mone jar hoy — that was the song. Mansooruddin’s text for Song no. 223 on page 142 of the second volume of Haramoni was exactly as Shamser Fakir had said. Others in the room also agreed. They heard in audible words in the recording because they already knew the song.

‘Diner katha mone jar hoy’. Page from Mansooruddin’s Haramoni Vol. 2, published in 1942.

I played more songs. Then they sang and I made a recording. Shamser Fakir’s dada or paternal grandfather Mukunda Fakir had sung ‘Tin baerar ek bagan achhe’ for Arnold Bake. Shamser Fakir and his friends sang it again for us. Then they sang more songs, ‘Diner katha’ too. And Aklima sang a song of Lalon Fakir. She was much travelled—hard worked in Lybia, Jordan, Qatar and then she also went to Saudia Arabia for Haj. ‘Now that you have gone on haj, you cannot sing anymore, I imagine,’ Uday asked. ‘Our system is different. Our faith is different. We can always sing,’ she said. We also talked about the time of ganja (cannabis) cultivation in this Naogaon region, when Bake had come, and when there used to be the gatherings of the fakirs at the plantations.

Shamser fakir sings ‘Tin berar ek bagan’ and ‘Diner katha’ playing his harmonium. There is a joyous participation of everyone gathered. They clap, play the mandira (small cymbals) and one plays on the plastic badna (pot for ablutions) as his hand drum. I remember Ahmed Moyez in London, who had used the popcorn tumbler for his dubki. That was way back in 2007.

They listen to the songs of Jaura Khatan Khaepi. I play them, one by one. They have no idea who she was. But I play the song ‘Namaz porite jai cholore’ and ask for a clarification. This is a question that had been on my mind for years. ‘How come she is singing about the importance of namaz? Does that not contradict the fakiri belief that namaz, roza, haj, jakat are mere rituals and what matters more is one’s intrinsic devotion and an inner piety?’ ‘She is not talking about the masjid outside,’ they explain to me, ‘but the masjid within. The “del masjid”, the shrine in the heart.’

‘I have some photos with me which I can show you, I said. Maybe you will recognise your grandfather?

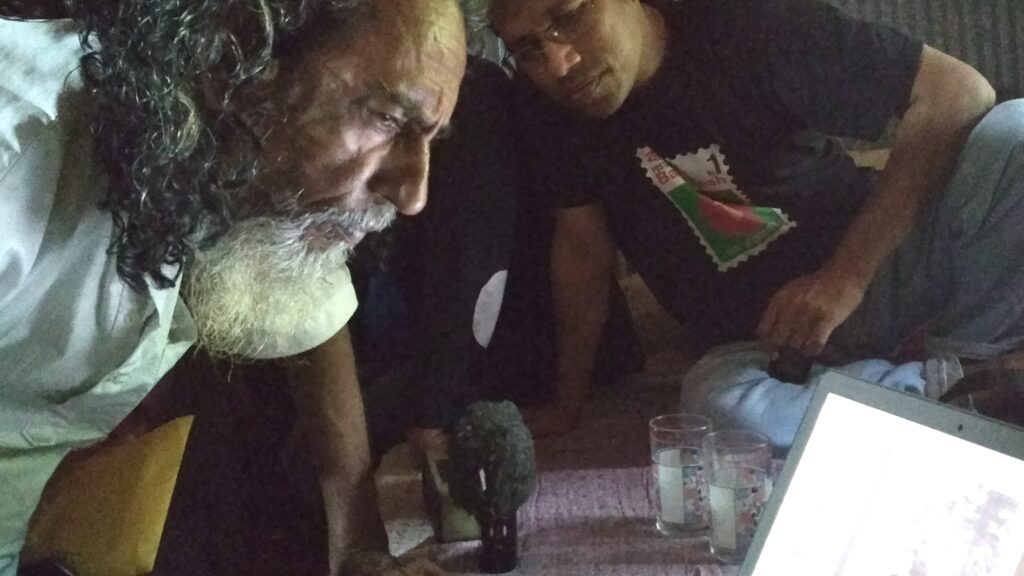

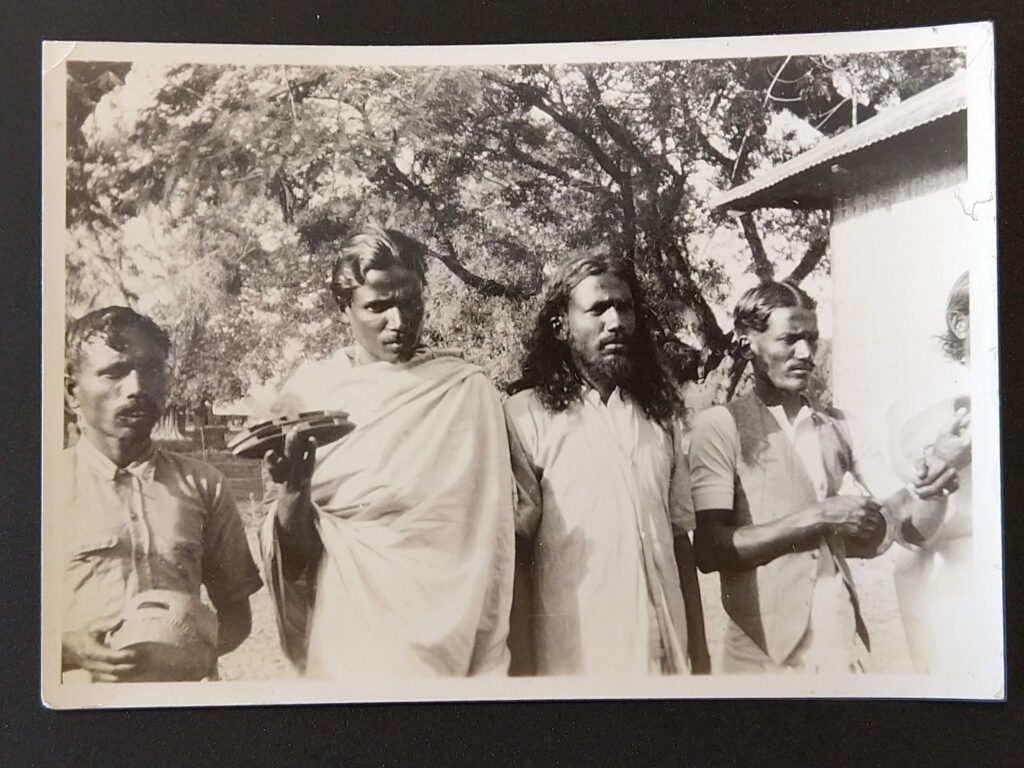

The ancestors in the black and white image in the centre is a photo of a photo from the Special Collections of Leiden University Library that I took in 2015. Above and below are two photos from this trip, The Dariapur fakirs are looking at/for their ancestors in the photographs.

I start showing the photos. They bend over my laptop. Shamser Fakir looks at Naogaon 9 and points to one of the four men standing with instruments. ‘This is Basir Fakir. I know him; spent so much time with him.’ I pause over Naogaon 7. Shamser Fakir moves even closer to the screen. ‘Ah, this must have been my grandfather!’ he said. I would think so too.

In 2019, I mostly concluded this series of trips in search of the fakirs whom Arnold Bake had recorded in Naogaon in 1932. Except that such journeys never really end. Abdur, Diljan Fakir’s son—did he get to sell his fish that day? What about the shrine of Basiruddin? Shall we go there at the time of their urs? What about our plans to meet again for an evening of music? Finally, who then was Jaura Khatan Khaepi? Kabari no longer lives in Shailagachi, where has she gone?

On our way back, we went to nearest point on the Chalan Beel from Dariapur, from where we got a boat to Bandaikhara and then walked over the bridge on the Atrai river and reached the bus stand to go back to Rajshahi.