Naogaon 1. September 2015

Arnold Bake had recorded the fakirs in Naogaon on 28 February 1932. Naogaon was a subdivision of Rajshahi district till 1984 and is now a separate district in northern Bangladesh. Bake India II Cylinders 83-94 are from Naogaon; 83-87 are names of male fakirs, 88-91 are of a woman named Jaura Khatan Khaepi, a fakirni . The rest, 92-94 are of ‘ganja workmen’ Azimuddin, Saura Ali and Komaluddin Sardar. Again, these are recordings I have heard at the British Library and ARCE, but now we also have copies of three cylinders, as we have just come back from an exhibition in London where we had some Arnold Bake recordings from the British Library as exhibits.

The word fakir is also written as fokir, even phokir in its Bengali to English transliteration, to bring it phonetically closer to both the ‘o’ sound and the closed-lip pronunciation of the Bengali letter ফ. However, Fakir is how Arnold Bake wrote, hence that is the spelling I have used to write about his work. I am also using Bake’s spelling for the name of the fakirni, Jaura Khatan Khaepi. But the name would possibly be written as Johura Khatun Khepi even at that time. My hunch is that Bake tried to write a spelling closest to what he heard and in those parts, they probably say Jaura for Johura.

Anyway, fact is that I was especially drawn to Jaura Khatan and had been musing on her for several years. Way back in 2013, the essay I wrote for the ‘La Presencia del Sonido’ (The Presence of Sound) exhibition had included some thoughts on her. She was for me the main point of this journey. Who was Jaura Khatan, mistaken as male in the BLSA catalogue notes (‘Āmi nāmāj parete jāi calo re Khaepi, Jaura Khatan (singer, male / ektara), a lone woman in a group of men whose photograph I had seen at the Leiden University library and copied with my camera?

The other intriguing point was the epithet ‘ganja workmen’. It took me a long time to work out what this meant, and that the ganja workmen were indeed people who worked in the ganja (cannabis) fields of Naogaon and that ganja was one of the main produces of the region, and what kept its economy and culture alive. By the time of this first trip to Naogaon, I had gathered some information about the cultivation of ganja in the region, but it was only after actually going there that I began to get a proper sense of the scale of its ganja operations at the time of Bake’s visit.

On this trip no one recognised the photos but the relation of the fakirs with ganja became evident. Ganja was banned in Bangladesh in the 1980s, the office of the Ganja Cooperative Society still stood in Naogaon, and its workmen managed old property and land now turned into markets and fisheries.

The fakirs used to come when ganja was grown, they said.

There was not that much sound to record, but more images and impressions to bring home. In fact, what I came back with was a feeling of incompleteness. I knew I would have to go back again.

That feeling had started to grow from the train to Rajshahi from Rajbari.

A man in our compartment who worked in the Railways got off at Ishwardi junction. Ishwardi—a name which comes with so much history! When we were going to Naogaon from Rajshahi, someone pointed to a highway and said, this is the road Ila Mitra had taken when she was fleeing the police; he was talking about communist Ila Mitra and the Tebhaga Movement of 1949. Subrata Majumdar, retired professor of mathematics with whom I was staying recounted how he had gone to see the terracotta temples of Puthia with the researcher and writer David McCutchion. Young folklorist Uday Shanker Biswas and Abdullah Al-Mamun, both lecturers at Rajshahi University, took us to a baul akhra in Bagolpara (Durgapur) in Rajshahi, to listen to Shamsul Fokir.

Uday Shanker Biswas is truly interested in local folklore and a collector at heart. I did not know this then but understand now after several years. These photos from 2010 were sent to me in 2020.

Recordings made at Bagolpara. Singer, Shamsul Fokir. Recorded by Sukanta Majumdar on 17 September 2015

What was the connection of all this with what Bake had recorded? I am not so sure, but this was only the beginning of a journey. In the beginning you have to indiscriminately collect your shells and pebbles from the shore.

We went to Mahasthangarh in Bogura, the Sufi shrine, to find something; who knows what? There we met Mahmuda, a woman who lives on the grounds of the shrine and sings of love and pain. The next year, I would write an idea for a soundtrack called ‘Who Was Jaura Khatan?’ which would be installed as part of our exhibition in Santiniketan ‘Time Upon Time: Arnold Bake in Bengal’. But we can come to all that later.

A song by Mahmuda, in which she sings: O lord, the kind one, your love is not so good as it brings pain. Tomar bhalobasha to bhalo na.’ Recordist: Sukanta Majumdar, 15 September 2015

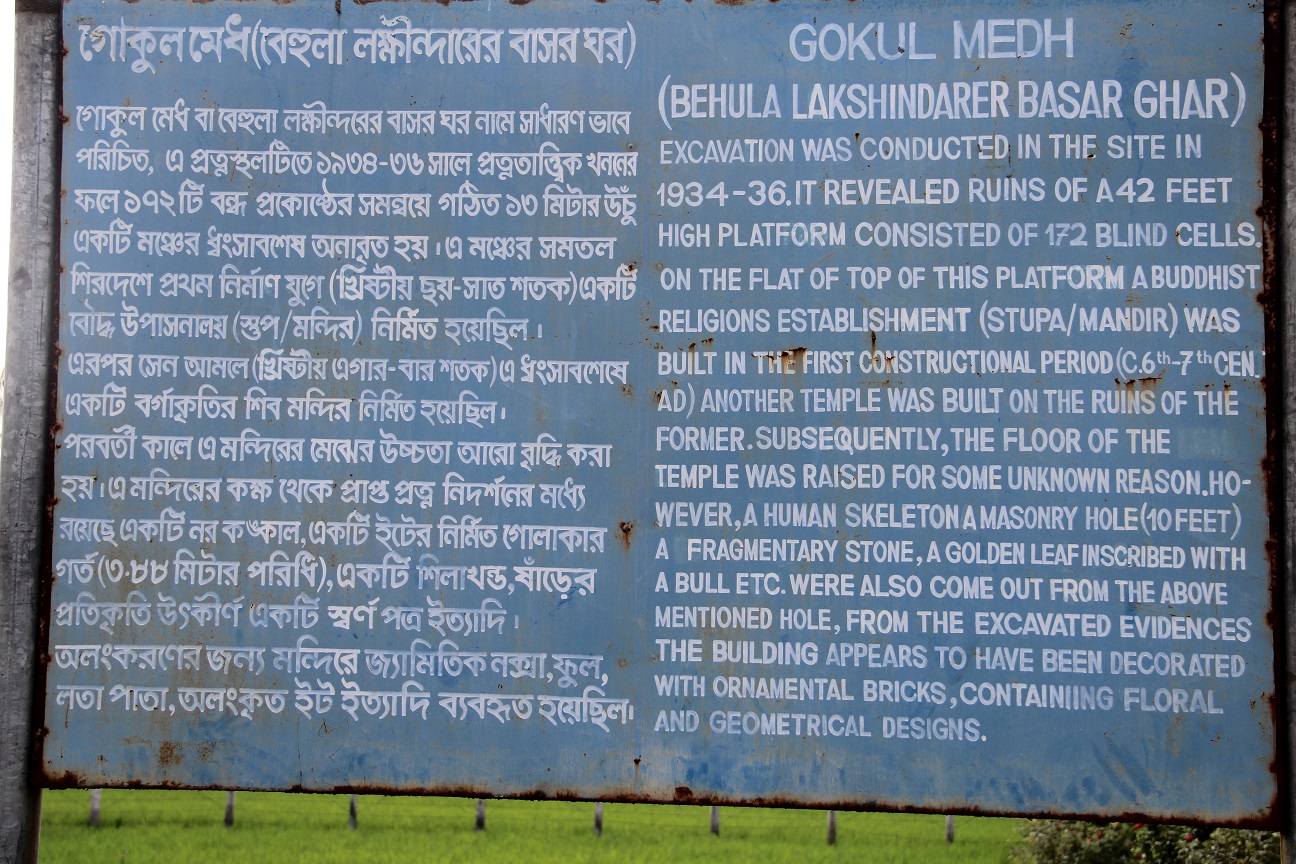

Mahmuda and her friends in Mahasthangarh share a joke. From here we went to Gokul Medh, below, a place of historical and mythological significance. There are songs and stories scattered along the way now, as they must have been in Bake’s time too.

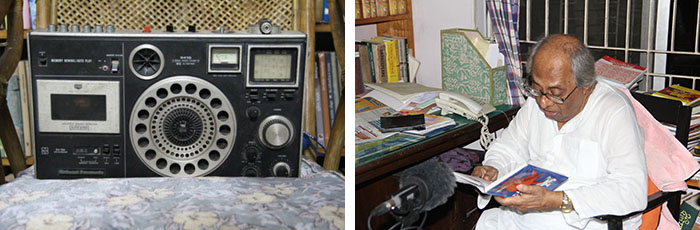

On this somewhat unfocussed trip, we were going from place to place, as if to find something–what, I did not quite know. Hasan Azizul Huq, the novelist, who had crossed the border from Barddhaman in the west to Khulna in the east first, just after Partition, and later moved through places and settled in Rajshahi, where he taught at the university, lived in the house next to Subrata Majumdar’s. We talked one evening about being torn between homes and he read from his writing for us. It was beautiful. There was an old radio cum tape recorder–a keeper and teller of tales–in the house of this fabulous storyteller. Such things always catch my eye.

Hasan bhai speaks. Recordist: Sukanta Majumdar, 17 September 2015