From Ranjan Shaha to Kobiyal Akhtar Shah in Kasba, Birbhum

The Berlin Phonogramm-Archiv catalogue describes Ranjan Shaha as Bettelnder Berufssänger from Kasba in Birbhum, which suggests an itinerant singer who lives by madhukori or collecting alms. Ranjan Shaha was a honey-gatherer. Arnold Bake recorded him in Santiniketan on two cylinders (Bake India II/81 and 82) in November 1931, the exact date is not known. He sang two songs, ‘Amar nai parer kori’ and ‘Michhe keno bhabona re mon’, playing the bowed sarinda. Both songs are about making the spiritual journey through life to reach the other shore—the first alluding to the Radha and Krishna story, where Krishna is the rower of the boat on the river of life and Radha is the one making the crossing. The second is a contemplation on the mind and mindless living.

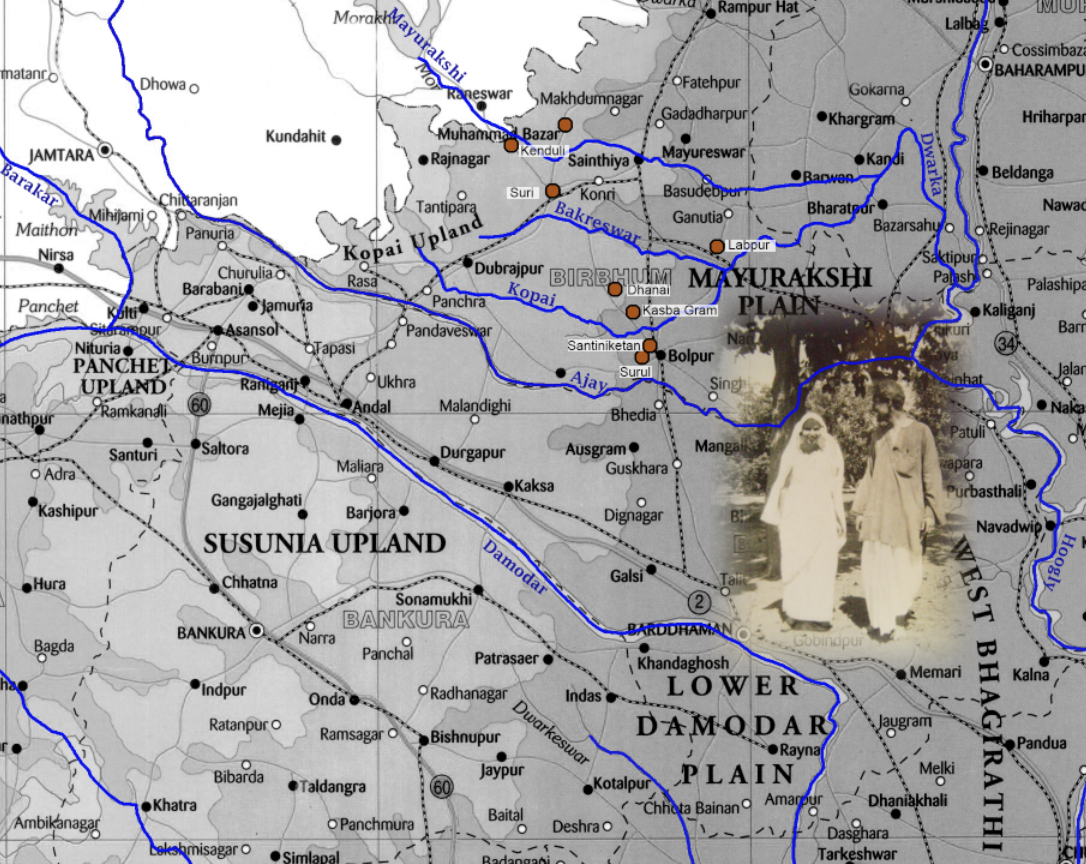

Map showing Kasba, Dhanai, Santiniketan, Suri and Kenduli. Designed by Purba Rudra.

On 15-16 June 2018, I went with my friend, field recordist Soumya Chakravarti, also a teacher in a sense, to Kasba village in Bibhum, about eight kilometres north of Santiniketan, in search of Ranjan Shaha. Soumyada had an acquaintance in the village, Anisur, who worked as a gardener. He became our guide on this journey.

Soumyada and I went by a ‘toto’, a battery-operated three-wheeler, to Kasba. Photos, mine.

There were no trails leading from Ranjan Shaha’s voice to any certain location—no family to be found, no lineage to link him with. However, there was room for plenty of speculation. I made recordings in Kasba, of various people, mostly in conversation. They suggested we go to all sorts of places; everyone had an opinion.

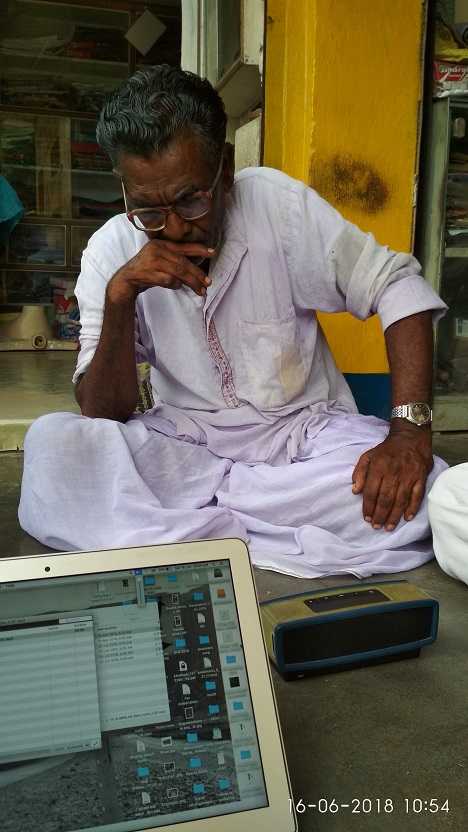

Hairdresser, Kasba. Photo, mine.

Man at hairdresser’s talks about the history of Kasba. The old zamindars who were Sahas, but they lost their fortune and dispersed. They settled near Mama-Bhagne Pahar. Take a bus, get off at such and such place, ask for so an so. Apparently Rabindranath had once come on foot to Kasba. Hard to know how far real and how much imagined these stories were. But the man was a great storyteller. Recorded on my Zoom H2N. 16 June 2018.

On the first day of our Kasba trip, what seemed most doable was to visit Dhanai, which everyone was suggesting. Dhanai was another eight kilometres north, and apparently it was a village of musicians. So, we followed that lead into Dhanai, where we were surrounded by curious listeners as we played Ranjan Shaha’s songs from my laptop. There was more speculation, but nothing concrete. This village could be Ranjan Shaha’s home too. They talked about musicians in their families, fakirs who roamed around, played the sarinda and sang. There was one prominent singer in their village, they said, Akhtar Shah, who could have told us more, but unfortunately he was away on work. Perhaps we could come back another day? Then Anisur, the gardener who grows little things in a plot which Soumyada shares with a friend, proposed a plan. No point waiting for too long. We could come back to Kasba the very next day and Akhtar Shah too could come from Dhanai to meet us. That way we could also have lunch with Anisur’s family, since the next day was the joyous Eid after the fast of Ramzan or Ramadan.

I give the recorder to Soumyada and he conducts the conversation in Dhanai, while I play Ranjan Shaha’s songs on my laptop, simultaneously making a video recording of Soumyada’s recording, with my phone. 15 June 2018.

As planned, the next day we went back to Kasba and kobiyal (singer of kobigaan or ‘a verse-duelling/song theatre genre’) Akhtar Shah of Dhanai came to meet us. He talked about generations of kobigaan singers in his family and also the use of the sarinda as an accompanying instrument. We realised that Anisur was in fact a murid or disciple of Akhtar Shah.

Akhtar Shah listens to Ranjan Shaha. Photo by me.

Akhtar Shah of Dhanai listens, then he starts to talk. 16 June 2018.

We do not know the exact circumstances of Bake’s recording of Ranjan Shaha’s songs; perhaps the singer was passing by his house, perhaps he was a regular in Santiniketan, came to sing like the bee and gathered honey from the asramiks; then flew back to his hive. While such songs certainly coloured the soundscape of Santiniketan, they were more like the breeze that blows over a place but does not stay. The occasional song collector keeps a record of this passing, that is all. Years later, we find traces of that voice in an archive thousands of miles away from the village.

I have tried listening to Ranjan Shaha not only in the field, but I engaged in a kind of ‘collaborative listening’ with the British composer Oliver Weeks and I also sent the recordings to Nirmalendu Mitra Thakur of Mainadal to know what he thought of the song ‘Amar nai parer kori’, especially since Ranjan Shaha sings a story about Radha and Krishna’s leela just as the kirtaniyas of Mainadal did. Within the space of an archive, multiple times and unconnected objects rest side by side without the parts knowing that they actually make one whole story. In my work, I have tried to get a dialogue going between those parts.

Nirmalendu Mitra Thakur and I had a conversation over the telephone on 19 January 2021. The starting point of the discussion was Ranjan Shaha’s song ‘Amar nai paarer kori, dayamoy Hori, paar koro nijo gune’. I asked Nirmalda to tell me the story of Hori or Krishna taking Radha across the river, to see whether what I had written down of Ranjan Shaha’s song—what I thought I heard in that recording, under its layers of noise—made any sense or not. Nirmalda says, ‘Sri Krishna, the boatman, is taking Radharani and her sakhis across the river. The cowherd maidens led by Sri Radhika come to the shore and ask Krishna to take them across. Radha says she has no money. There is some haggling—he asks for sholo ana [sixteen anas make a whole taka], he asks for all. She says I don’t have sholo ana to give, I can at best give half, I can give aat ana.’ Nirmalda shies to tell me details of this story with its erotic symbolism. There are implied meanings, they are talking about both deho (body) and mon (mind), after all. Radha and Krishna are playing with words, he is propositioning to her and she and the girls and the old woman escorting them are dodging his advances with clever retorts. Nirmalda says some, hides some, sings some, and laughs some. I cannot ask very directly either. There is a curtain between us in this exchange, and the listener will hear it fluttering in the breeze in this conversation. ‘Well, I mean, is there anything about bastra or clothes in this story? I thought I heard the word in that other song,’ I ask. ‘Indeed there is,’ Nirmalda says. ‘Sri Krishna says your blue sari is inviting the rain clouds, if the rain comes our boat will sink. You need to take it off. Radharani says, what about your blue body? Can you shed that too?’ Nirmalda says, ‘This is all about leela or divine play, you know.’

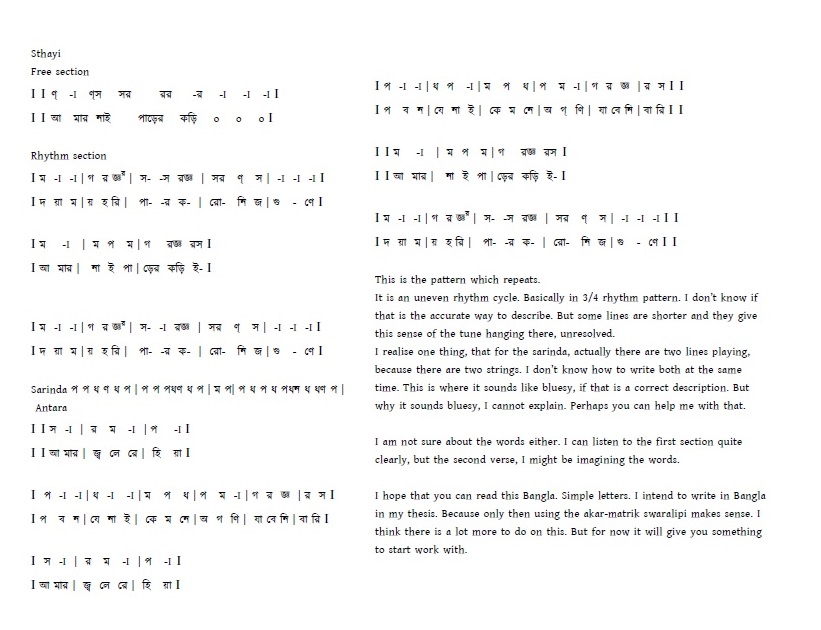

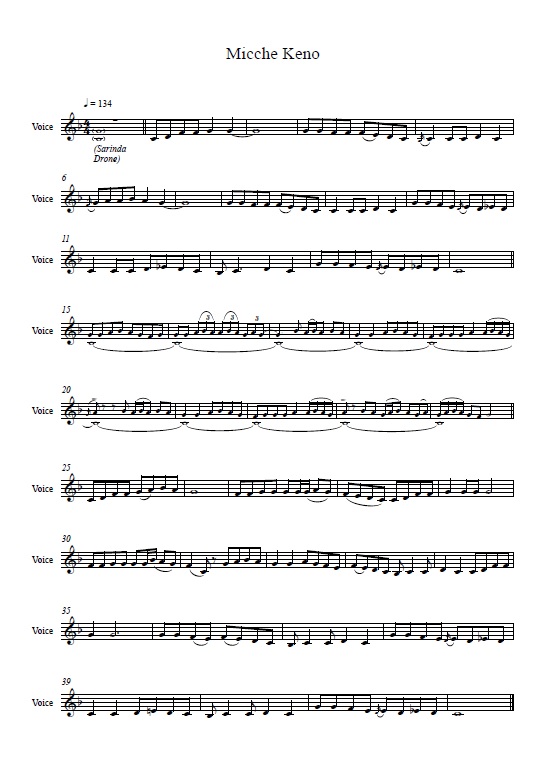

My notation, attempt at writing the words and a brief note to Olly

Sound engineer Abhimanyu Deb had done some noise reduction on the recordings for me, for enhanced listening. I zoomed into the sound of Ranjan Shaha’s songs, trying to write the words. Then I sent a note to Olly. The idea was that we would compare our listenings and our ‘translations’ across media—from sound to text and text back to sound. Moreover, the main thing for me has been to find a face and a place for a song. Where do we go in its absence?

Ethnomusicologists commonly write down their listening as notes and notation. I have very rarely tried out this exercise; I am also not equipped for it. However, Olly Weeks is such an evolved musician and composer, that with him it was easier for me to venture into the world of signs, trying to create other meanings with these old recordings, mixing languages and sonic textures. It is interesting to note how the song shifts from the source and changes meaning as it moves through different places, different perceptions and finds a place in different voices.

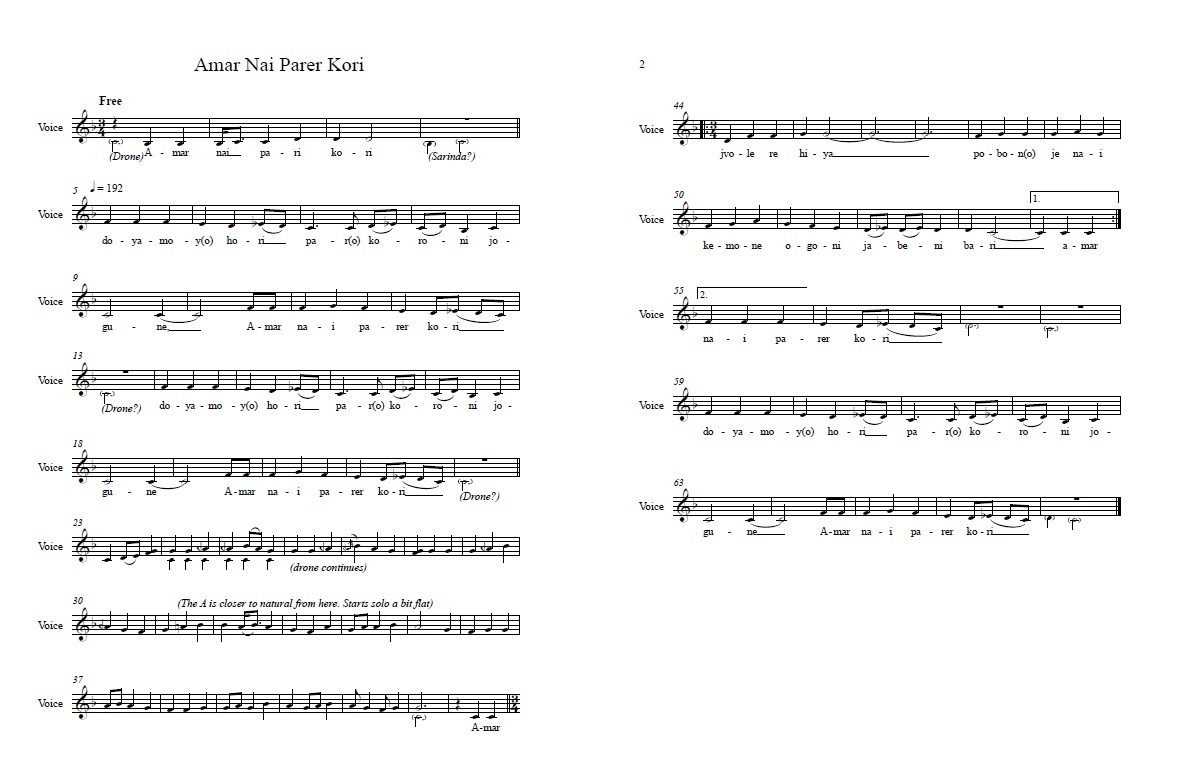

Oliver Weeks notates Ranjan Shaha’s songs and sings them too.

Meanwhile, on 16 June 2018, Anisur showed us around Kasba village: the old abandoned house of the zamindars, with trees growing in its cracks. This space inspired Anisur to sing a song for us. Soumyada said, ‘Aare, Anisur! Never knew you could sing!’ Back in his house, the family, dressed in their Eid fineries, posed for a group photo with Soumyada, while Anisur’s son showed off his bluetooth speakers.

- Laksmisvar Sinha, a Doorway to Many Worlds

- Imam Bux Boyati of Mymensingh at Gurusaday Dutt’s Suri Mela

- Motru Sen and Jaya Tagore: From Image to Sound

- Mapara’s Cradle Song and Shruthi Vishwanath’s Response

- The Bauls of Kenduli in 1932

- Pinakin Trivedi and the Autograph Book

- Roof-Making Songs of Baori Women

- Listening to Savitiri Govind with Sumana Chandrasekhar

- Kusum, the Nachni and her Jhumur

- From Gurudayal Malik to Mohan Singh Khangura and Madangopal Singh