In Mongoldihi, November 2015

There was Arnold Bake’s footage of kirtan that we had taken to show to the kirtaniyas of Mainadal in 2014 and the then oldest singer of the Mitra Thakur family, Sri Manikchand Mitra Thakur (died 2018), had said that perhaps the singers in Bake’s film were from Muluk village (not far from Bolpur-Sriniketan). Musicians are seen playing multiple instruments including the shinga (the S-shaped horn) and shanai (shehnai), and a violin and khol (clay drum played with the hands) and dhak (played with sticks), and it looks like a veritable orchestra. There are singers too.

The Arnold Bake archive catalogue of the Berlin Phonogramm-Archiv gives the following details for Cylinders 76-79:

76. Mongoldihi, Nov., 1931.

Kirtan (tal Lopa.) Rag jhingit

77. idem. One Shannai, tal lopa, rag jhinjit

78. Kirtan idem.

79. idem. Instrumantel. 3 shannai, one khol, one cymbal

Could this film be from Mongoldihi? Could these songs be from the same place, recorded on the same day?

When we launched this website in 2011, we had this film from ARCE , we did not have enough knowledge to judge the opening lines: ‘Kirtan music in honour of God Krishna by low caste villagers’. Yet, these instruments did not seem to corroborate with our own limited the idea of the sound of kirtan. Hence, we superimposed our own judgment on the footage: ‘…this does not look like kirtan. Even Bake’s own recording of kirtan does not match the instruments shown here.’ I am not erasing that subtitle now, in 2021, as it shows something of my way of working–going to the same place and same song and same archival recording over and over, because that is the only way for me to learn and correct past errors. I have uploaded the film here again, this time the version I had from Amy Catlin-Jairazbhoy, with Bake’s opening statement inverted.

The reason I could not see this footage as Mongoldihi’s is because I had not heard the Mongoldihi recordings, even till the time of my visit to Mongoldihi. What I had from ARCE for cylinders 76-79, and what I also have from the Berlin Phonogramm-Archiv are recordings from Nepal (I think) instead of the kirtan and so some mix-up has happened somewhere along the line. The British Library opened their listening platform after 2016, perhaps in 2017, and now the actual Mongoldihi recordings can be heard here. Click on 11/31 and you will find a range of sounds—the shinga and the Santal flute and kirtan—and you can feel the presence of the many people who were part of Arnold Bake’s field that day on 26 November 1931. Not just the people we see in the film, but others too. About this day he later wrote to his mother: ‘We were too tired to go out in the evening. The next morning started with a performance before the magistrate; first by school children, then all kinds of musicians, singers and instrumentalists, with whom I was occupied until about one o’clock. I got six cylinders worth of material, if I’m not mistaken, and a bit of film too.’ So this indeed is that film that we are seeing.

In his letter of 26 November, he also wrote: ‘Wednesday evening was the great procession. The statues of Balarama and Krishna were carried out of the temple with music and song and taken to a little place …[which had been prepared for their landing]. There they were put down, and the conch was blown, while fireworks were lit to celebrate and honour the deities. Mr Datta [Gurusaday Datta, the then District Magistrate] could get very close, and we were allowed to get close all over, much closer than we have ever dared ourselves. There was a hell of a crowd on the way, but not as much as the other years, because this year the country has just been decimated by malaria. Mongoldihi was only at half strength, and just yesterday we heard that in Surul fifty people had died. [Here the poor] People have very little resistance.’ (Translated from the Dutch by Jan-Sijmen Zwarts). Bake was describing the Raash Utshob.

We heard stories about the tradition of Raash Utshob in Mongoldihi, the tradition of the music, the shinga players and where they came from, the Santal flute, and dance and what has become of the place now. I went to Mongoldihi on another 25 November, 84 years after Arnold Bake. I went with the painter Milan Mitra Thakur, whom we first met in Mainadal the previous year and who had by now become someone I could call anytime and ask for clarification and advice—a mentor of sorts. Also someone who was emerging as their own archivist (See how Milanda is taking a leading role in gathering recordings and other material related to the Mainadal Mitra Thakur family’s heritage). Many of the photographs of my Mongoldihi trip were taken by Milanda.

Sukumar Banerjee, Diptendranath Narayan Thakur, Samitendra Narayan Thakur and others talked about their Raash Utshob in Mongoldihi. They also talked about the spontaneous participation of the Santals in the festivities in the past, their flute sounds, and how some of that spontaneity is now lost, giving way to caution.

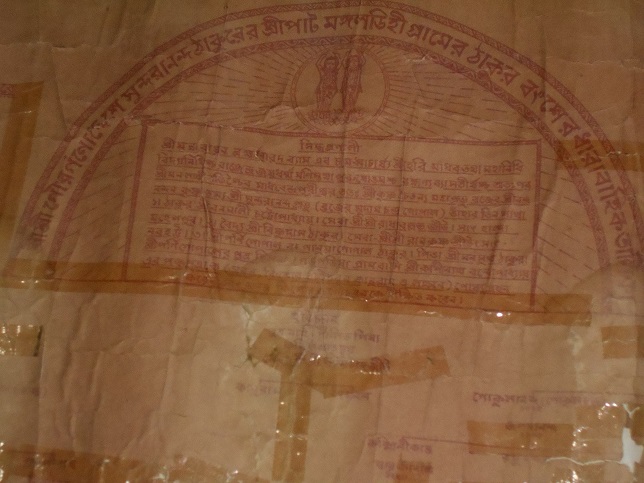

They talked about their house deity and showed the family tree. Milanda poured over this genealogy chart with Sukumar-babu. It reminded me of Mainadal and how they sing their ancestors’ names at the end of their Nandotsav festival.

Then we watched Bake’s film together.

Watching Bake’s film with the Mongoldihi family. Photo: Milan Mitra Thakur

The Mongoldihi people were excited to see the musicians and the musical instruments, but they were disappointed that none of their ancestors had been filmed.

Music and conversation with musicians Dhiren Das, Dhorai Das, Manik Das. Dhiren Das said his family had been playing at Mongoldihi’s Raash Utshob for generations.

Some faces bear shadows of the faces in Bake’s film

The conversations in Mongoldihi happened before the main festivities began. Then Milanda and I went roaming to see the mela.

Then the gods were taken out and crowds of people walked in a procession, much like Bake’s description in his letters.

- Manoharsai from Sumati Devi of Manipur

- Manipur Univisited

- In Search of Nabadwip Brojobashi

- Nirmalendu Mitra Thakur Explains Bake’s Kirtan Recordings, 2021

- Found Film: Janmashtami and Nandotsav in Mainadal, 1994

- Kirtaniya Seema Acharya Listens to Olly

- Olly Weeks Reads Bake’s Kirtan Notation

- The Niyomsheba Songs, October 2014

- First Time in Mainadal, August 2014