From Gurudayal Malik to Mohan Singh Khangura and Madangopal Singh

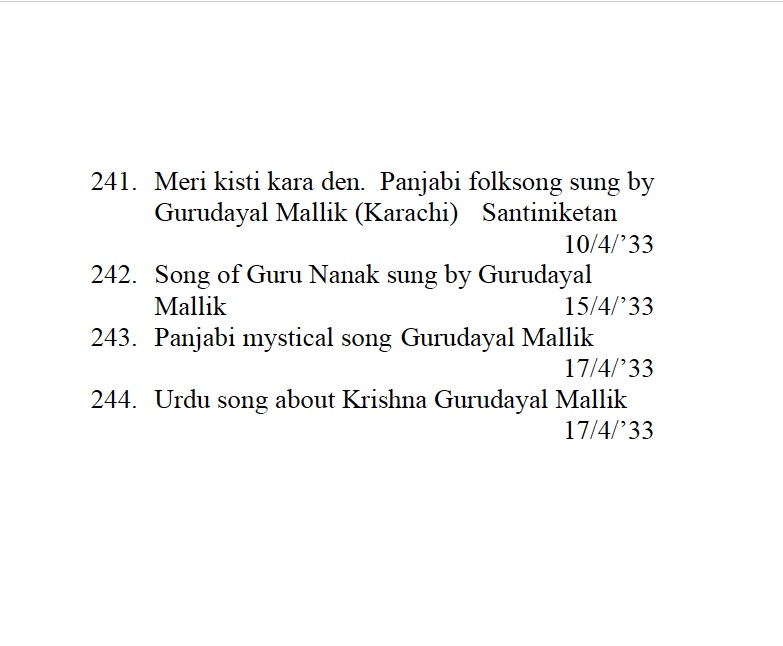

Gurudayal Malik (1896-1970), from Karachi, taught English to school students in Visva Bharati. Between 10-17 April 1933, Arnold Bake recorded him in the asram; he sang four mystical songs in Punjabi and Urdu on Bake India II cylinders 241-44.

During the first phase of his Santiniketan stay between 1925-29, the medieval saints of India were a major subject of discussion between Arnold Bake and Kshitimohan Sen.

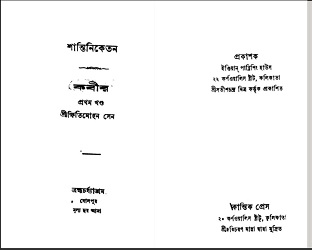

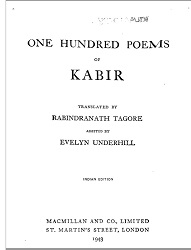

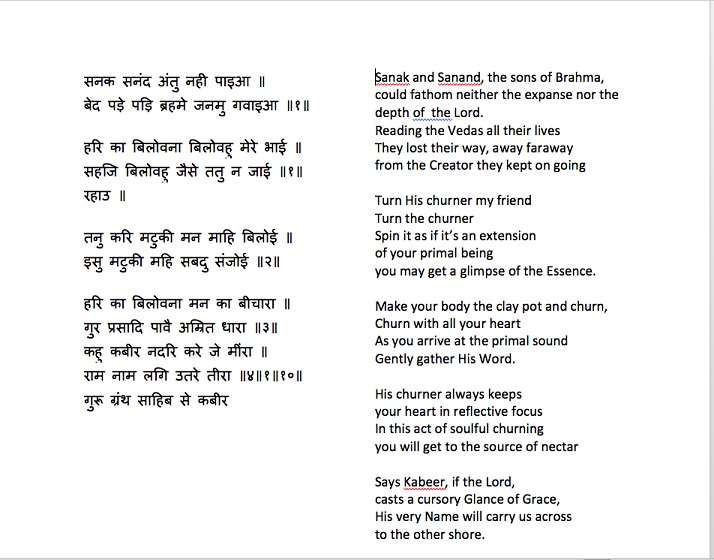

From left to right: Pages from Kshitimohan Sen’s anthology of Kabir’s songs, published in 1910; Kshitimohan’s book on the medieval poets, translated by Manmohan Ghosh; finally, Rabindranath’s translation of Kabir, with Everlyn Underhill, based on Kshitimohan’s anthology, first published in 1915.

They would go for walks together, besides having more formal lessons, and talk. Bake would attend Kshitimohan’s lectures. Bake was learning so much about the mystical poets and medieval saints of India from ‘Kshiti’, as he wrote in his letters home. For example, in his letter of 24 February 1926, he wrote page after page about Kabir, Dadu, Ramananda, Ravidas, Jnanadas and so on. Bengali author Pramathanath Bishi, one of the first students to join the Santiniketan asram as a boy, had written about how students used to be quite scared of Kshitimohan, mainly because of his sombre presence. ‘Yet it will be difficult to find someone who has not benefitted from his teaching,’ he wrote. ‘He would draw the student into the maze of difficult and dry topics and would light up the way of learning by striking the magic stone.’ Arnold Bake, we must remember, was not Kshitimohan’s student in the sense the asram boys were. He was a mature learner who had come from a distant land, who was also becoming a friend. There are some beautiful family photos of the Sens and the Bakes; Kshitimohan’s daughters would have been about the same age as the Bakes.

The Bakes with Kshitimohan Sen’s family, possibly taken in the late 1930s. Photo courtesy: Shibaditya Sen, my departed teacher and grandson of Kshitimohan. Shibda had dated the photo by seeing his older cousin, Amartya (later to become the famous Nobel laureate economist Amartya Sen), third from the left in the front row. Amartya Sen was born in 1933 and the boy in the photo will be about five or six–that was Shibda’s calculation.

On 28 December 1926, Tuesday, Arnold Bake had written to his mother that the previous Friday, at about two in the afternoon, they had heard beautiful songs coming from the school of music. ‘This doesn’t happen very often, so we raced to see who it was. It turned out to be Mallik [it is interesting that Arnold Bake wrote Mallik, the Bengali surname, for Malik; the catalogue too has Gurudayal’s name as Mallik], a singer with a strong mystic disposition (maybe we already wrote about him last year, his farewell party was held just a few days after we arrived. He left to help is father, who is a very wealthy merchant in Karachi). Mallikji knows volumes of mystical songs, and he sings them with a rare beauty. His voice is a hundred times better than what is ordinarily found; but even without it, it would still be more than worthwhile to hear him sing, because he pours his soul into it. It is exceptionally touching. He was here only for a few days, but his dream is to come back and work under Gurudev, when his father will grant him leave.’ (Translated from the Dutch by Jan-Sijmen Zwarts)

From Berlin Phonogramm-Archiv’s list of Bake cylinders.

Arnold Bake’s relationship with Gurudayal Malik’s song, which began in 1926, continued through 1933 right up to 1950. Bake kept a record of the impression Malikji’s songs made on him in his letters; he recorded him with his machine; even archived his songs in his own body. In a lecture Bake gave in The Netherlands in 1950, talking about Indian folk and classical music, he sang one of the songs that Gurudayal Malik had sung for him on 17 April 1933, ‘Meherban meherban, sahib meherban’.

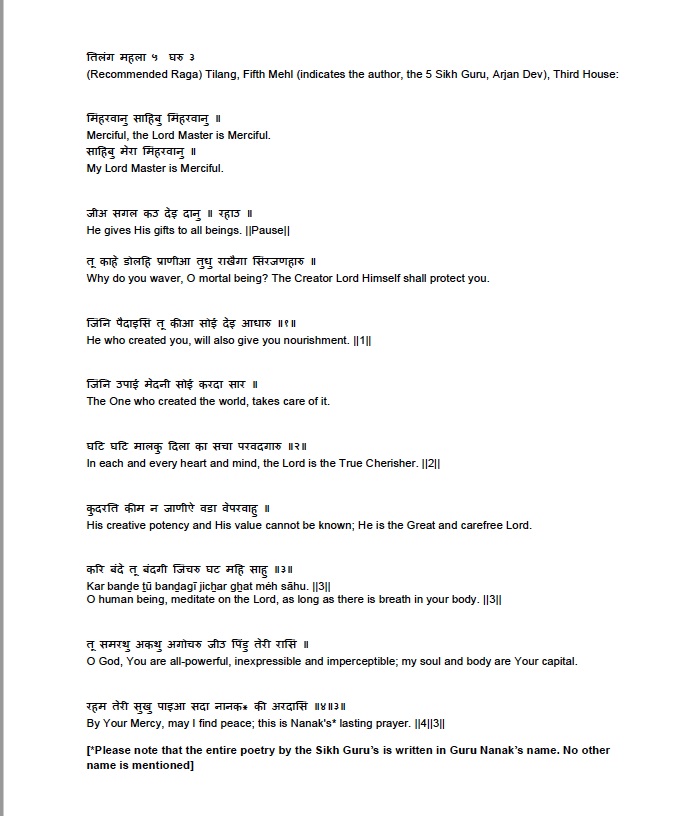

I shared the recordings of Gurudayal Mallik with Punjabi Sufi singer, Madangopal Singh to learn his thoughts and he sent me texts of the songs with some explanation (the above note is from one of his emails to me written on 3 November 2020). The song ‘Meherban meherban’, which Bake used to also sing, and which is mentioned as a composition of Guru Nanak in the catalogue notes, is in fact a composition of the fifth Sikh guru, Guru Arjan. Madanji wrote: ‘The entire text [as you can see above] is given here in Devnagri script with English translation as approved by the Sikh body, SGPC, whose knowledge of the English language is suspect in the best of circumstances. Two things could be special interest to you: a) The ‘shabda’ – hymn – is unambiguously attributed to the fifth Sikh Guru, Guru Arjan. Guru Nanak was the first Sikh Guru. He was followed in the line by Guru Angad, Guru Amardas and Guru Ramdas. Guru Arjan happened to be Guru Ramdas’s son and was martyred on the banks of the river Raavi in Lahore in the 16th century by a repressive state. b) Since the last stanza mentions the name Nanak, it may give rise to the suspicion that the author of the ‘shabda’ is Guru Nanak himself. That, in fact, is settled right in the beginning where the Mehla 5 is mentioned, that clearly identifies the fifth Guru as the author. It may be further mentioned that after Guru Nanak, no other Guru used his own name in any of the ‘shabdas’ he wrote. The name of Guru Nanak is used throughout from the second to the ninth Guru. That has been the practice.

‘A minor point finally: the recommended Raga is Tilang but it is by no means mandatory to sing in that Raga.

‘Of course, there are some textual deviations in the audio files sent by you and I can tell you that had the Sikh clergy got wind of that in the thirties, there would have been a minor storm in the poetic teacup of Mr Malik.’

Madanji also wrote about another song from that list. ‘The other song as I mentioned is a Prabhat Pheri (literally, the Early Morning Musical Walk of the mendicants) bhajan with a cleverly concealed message for the people to rise against the British regime.’ I kept pleading to Madanji to send me a song in response to what I had sent him. He said, ‘Much as I wouldn’t want to say “no” to any of your requests, yet despite trying over and over again, I have not been able motivate myself to either respond to the voice or the melody you had sent from your archive. I will most reluctantly have to say ‘no’. With warm regards from a diehard fan of your singing, scholarship and research, Madan’. I kept at it, though, and then Madanji sent me this absolutely beautiful song of Kabir, with his own translation.

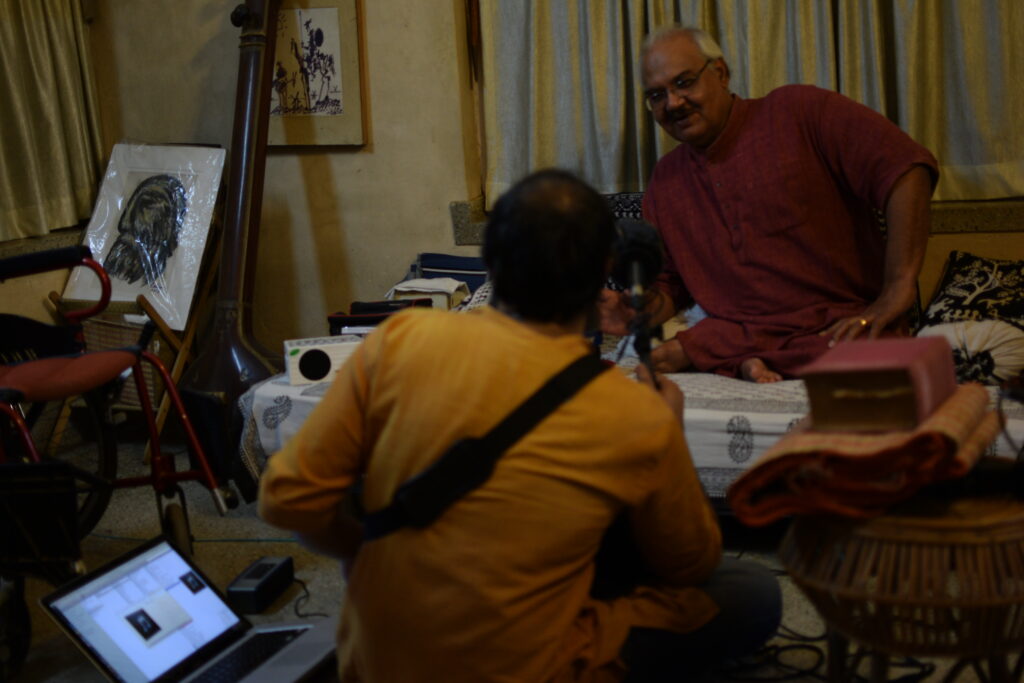

In 2016, while preparing for The Travelling Archive’s exhibition in Santiniketan, Time upon Time: Arnold Bake in Bengal, we had gone to meet the famous Tagore singer and retired professor of Sangit Bhavan, Visva-Bharati, Mohan Singh Khangura in his home.

Mohan Singh Khangura being recorded in his home in Santiniketan by Sukanta Majumdar. 11 March 2016. Photo by Jan-Sijmen Zwarts.

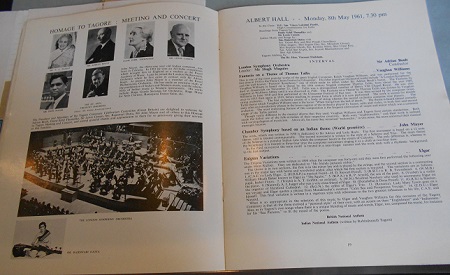

The choice of Mohan Singh was obvious; as there was a sonic continuity from Gurudayal’s voice to his, also a geographical contiguity, as both had journeyed from Punjab to Santiniketan, even if many years apart. In 1938, singer Rajeswari Datta (then Vasudev, later married the poet Sudhindranath Datta) had also come from Lahore to Santiniketan and studied in Sangit Bhavan for four years. Again, a journey from Punjab to Bengal, pulled by the songs of Tagore. I wonder why Bake never mentioned Rajeswari, or maybe he did and I am not aware of it, since she was one of the finest singers of Rabindrasangit we have ever had and they were contemporaries too. Both of them were part of the Tagore centenary celebration in London in 1961. Incidentally, Rajeswari also taught Indian music at SOAS, but that would be after Bake.

We can listen to a Rabindrasangit of Rajeswari Datta ‘Kichhui to holo na’ here

Anyway, coming back to Mohan Singh, or Mohanda, he sang some examples of Punjabi kirtan or ‘Asa di var’, and then he sang a ‘shabda’, and a song of Bulleh Shah and one of Kabir. These are absolutely precious recordings; they were made by Sukanta Majumdar in the presence of Mohanda’s older son Abir and the Director of the Archives and Research Centre for Ethnomusicology, Gurgaon, Dr Shubha Chaudhuri. The date of the recording was 11 March 2016. I cannot remember the name of the tabla player.

A test recording, as Mohanda wanted to make sure the sound was alright

Mohan Singh sings a Punjabi ‘shabda’ or devotional song as is sung in gurdwaras

Mohanda sings a song of the 17th century Sufi poet of Punjab, Bulleh Shah. Then he says, no one to learn such things here, none to listen even. But I sing for myself.

Mohan Singh sings ‘Awal Allah noor upaya’, a song of Kabir

The celebration of the plurality of faiths and engagement with the Bhakti and Sufi saints and poets has been part of the culture of Santiniketan from its inception. It found its fullest expression in Binode Behari Mukherjee’s ‘Medieval Saints’ mural, which adorns the walls of the university’s Hindi Bhavan. The work was completed in 1947.

Source: Chakrabarti, Jayanta, R. Siva Kumar and Arun K. Nag eds., The Santiniketan Murals (Kolkata: Seagull Books, in association with Visva-Bharati, 1995). I thank artist Syed Taufik Riaz for lending me his copy of this book.

- Laksmisvar Sinha, a Doorway to Many Worlds

- Imam Bux Boyati of Mymensingh at Gurusaday Dutt’s Suri Mela

- Motru Sen and Jaya Tagore: From Image to Sound

- Mapara’s Cradle Song and Shruthi Vishwanath’s Response

- The Bauls of Kenduli in 1932

- Pinakin Trivedi and the Autograph Book

- Roof-Making Songs of Baori Women

- Listening to Savitiri Govind with Sumana Chandrasekhar

- From Ranjan Shaha to Kobiyal Akhtar Shah in Kasba, Birbhum

- Kusum, the Nachni and her Jhumur