Communal Listening in the Dumka Hills

They were all insiders to the sound of Arnold Bake’s recordings from the Dumka Hills, yet they were all different too. The listening sessions in Kairabani, Harinsingha, Jamuasol and at Johar and NELC in Dumka in Dumka town, revealed a range of reception and interpretation of the sounds held in Bake’s Santal cylinders. The insider-listeners responded from their individual social, economic, historical and cultural locations, since any community is not one homogenous group but it is complex, fragmented and layered; an assemblage of multiple communities within a community.

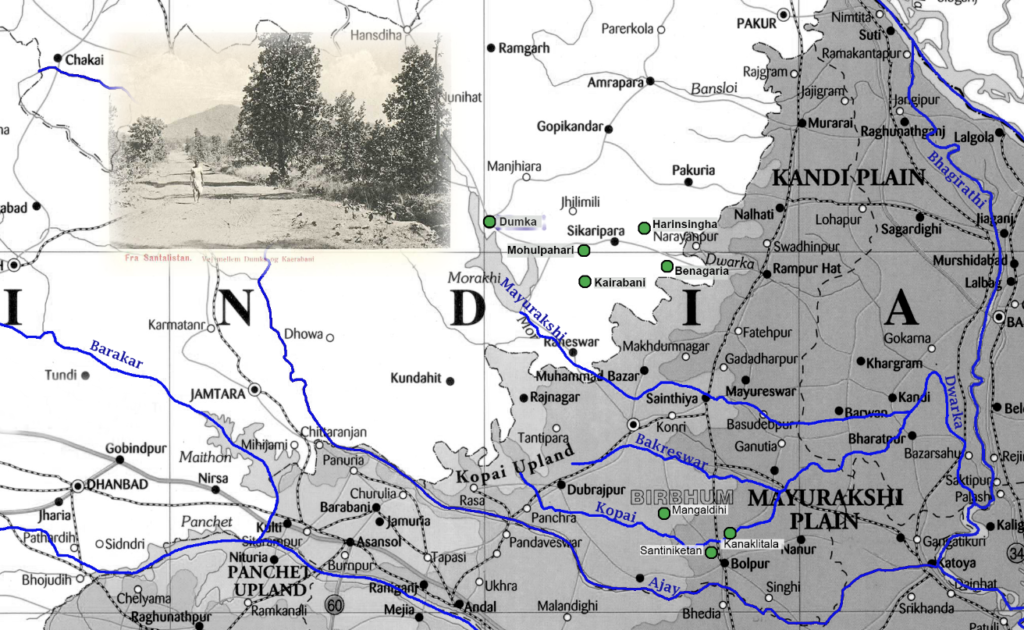

The Dumka Hills. Map designed by Purba Rudra, 2021.

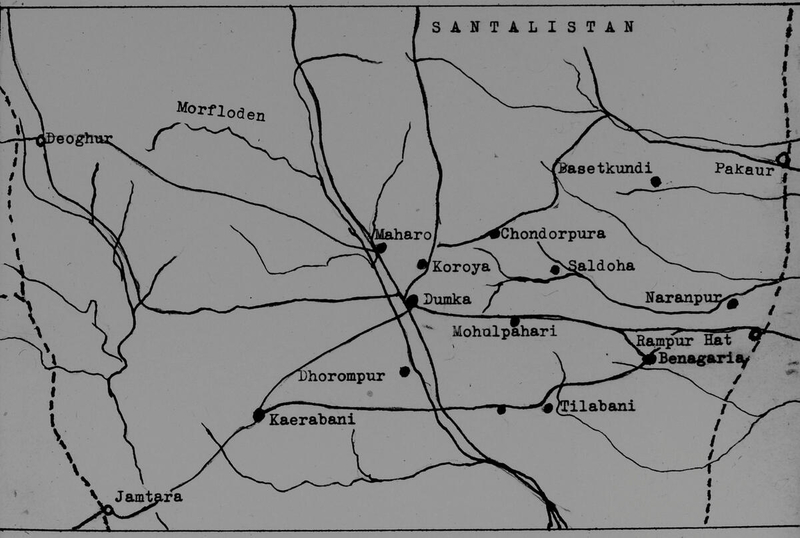

Old map of Santalistan, from the digital library of the University of South California. Source: Danmission Photo Archive. Rights: CC Attribution (CC BY). https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/ Permanent link: http://doi.org/10.25549/impa-c123-104208

In 1931, within a couple of months after returning to India and settling back in Santiniketan, Bake had started to make preparations for going to the Dumka Hills in the Santal Parganas (now the state of Jharkhand). He got in touch with the Norwegian missionary and pioneer scholar of Santal Studies, Dr Paul Olaf Bodding (1865-1938), who was secretary of the Santal Mission of the Northern Churches and was stationed in Mohulpahari. Dr Bodding was not only a great scholar and linguist, but he was a collector of local knowledge and an archivist. His work can be seen as a living archive of the Santali language, grammar, folktales and folk medicine.

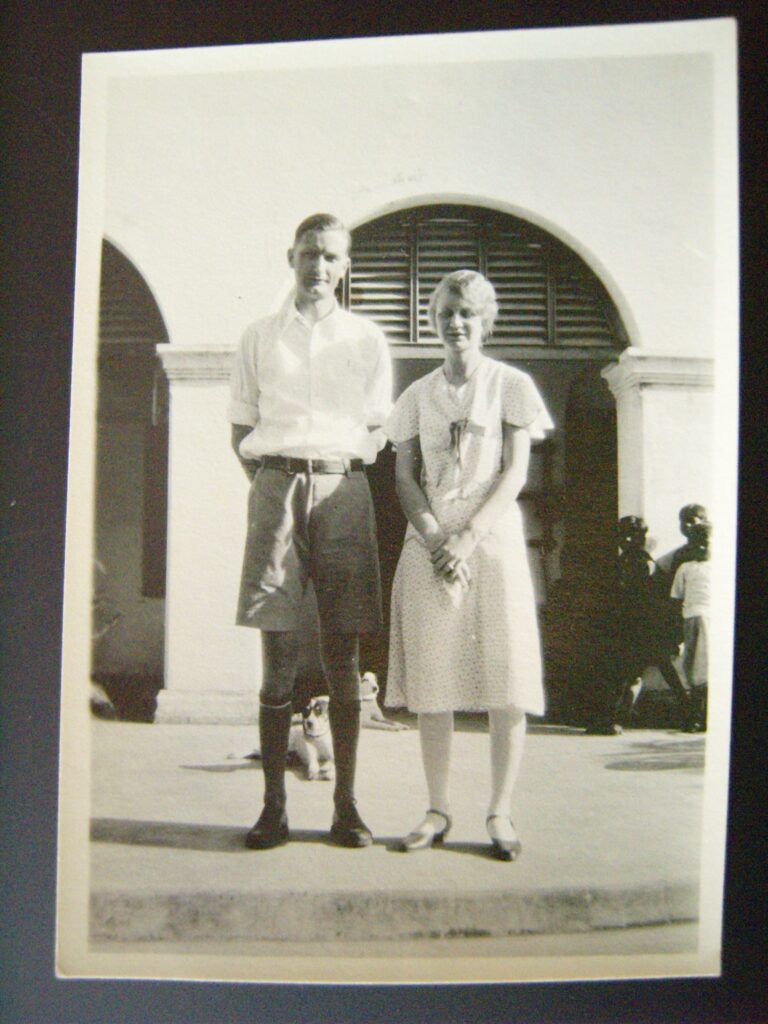

This photograph, of Dr Paul Olaf Bodding and his wife Christine, was taken in Darjeeling in 1930. Therefore, this is how Dr Bodding would have looked when Arnold Bake met him. It’s source is the digital library of the University of South California. The Danmission Photo Archive. Rights: CC Attribution (CC BY). https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/ Permanent link: http://doi.org/10.25549/impa-c123-98677

The Santal Mission ran a boys’ boarding school and church in Kairabani, which also had a choir and a brass band. It was Bake’s friend, the American missionary Boyd W. Tucker, close associate of Gandhi, who taught English in Santiniketan, who connected him with Rev. Bodding, and the latter then invited him to Kairabani, since he was interested in recording Santali music. After a few aborted plans owing to bad weather and the unavailability of Mr Gurusaday Dutt–the district magistrate of Suri, who would facilitate the trip–the Bakes finally set out for Kairabani, 30 kilometres southwest of Dumka, on 17 March 1931.

The Kairabani Mission school now, photographed by me in January 2017.

Kaerabani (Kairabani) missionary bungalow, built by the German Baptist Missionary, Albert R. Haegert, who died 1904 (then the house was bought by the Santal Mission in 1905). The photograph is from the digital library of the University of South California. Source: Danmission Photo Archive. Rights: CC Attribution (CC BY). https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/ Permanent link http://doi.org/10.25549/impa-c123-98602

After the trip, Bake wrote to Erich M. v. Hornbostel at the Berlin Phonogramm-Archiv that this was just the first trip, he would have to go back to record the Santals again. Mostly because he could not record Santal dance in the mission as those who rain the mission were not keen on dance. Bake could not go back to Dumka, however; instead, he the recorded and filmed the Santals at Kankalitola and Mongoldihi, nearer home, in Birbhum later that year.

Film copy received from Archives and Research Centre for Ethnomusicology (ARCE), Gurgaon.

Bake India I, Cylinders 1-8, were recorded between 17-20 March 1931 in Kairabani. It is with those recordings that I went with sound recordist Sukanta Majumdar to Dumka on 21 January 2017. Some recordings from that trip can be heard here. Achyut Chetan, who taught then in the local S. P. College and whom I knew through a friend in Santiniketan, put me in touch with Father David Madhava Solomon, SJ, Director of Johar Human Resource Development Centre, also in Dumka, Jharkhand and that became our starting point. Sushant Soren, a young activist who worked with Johar, was our main guide and interpreter on this trip. I have travelled to the field with companions but rarely with an interpreter or guide, but this trip was different. I was consciously aware of my distance from the field, the language and the subject I was seeking to explore, from the very onset of the journey.

On 22 January 2017, we went to Kairabani Dudhani, the village where the Kairabani Mission was situated. We sat on the veranda of a house from where the Mission could be seen, but the villagers who had gathered were not attached to the church. Rather, they were quite critical of the role of the church in their communal life. Slowly a crowd of some 20-25 people gathered as we sat on the floor and played the songs. I explained the context in Hindi, Sushant Soren translated what I was saying into Santali, and the songs were played from the laptop, through portable speakers. The villagers listened and responded and chatted amongst themselves and Sushant translated some of their responses back to us and some things he left out.

Listening in Kairabani, 22 January 2017. Photos, The Travelling Archive.

Interestingly, Sushant Soren, with his notebook and pen, was also an outsider in Kairabani. What he said was explained to the villagers by one member of their group who had a job with Calcutta Telephones, Shivsadhon Kisku, about 55 years old. Kisku spoke fluent Bangla and Hindi.

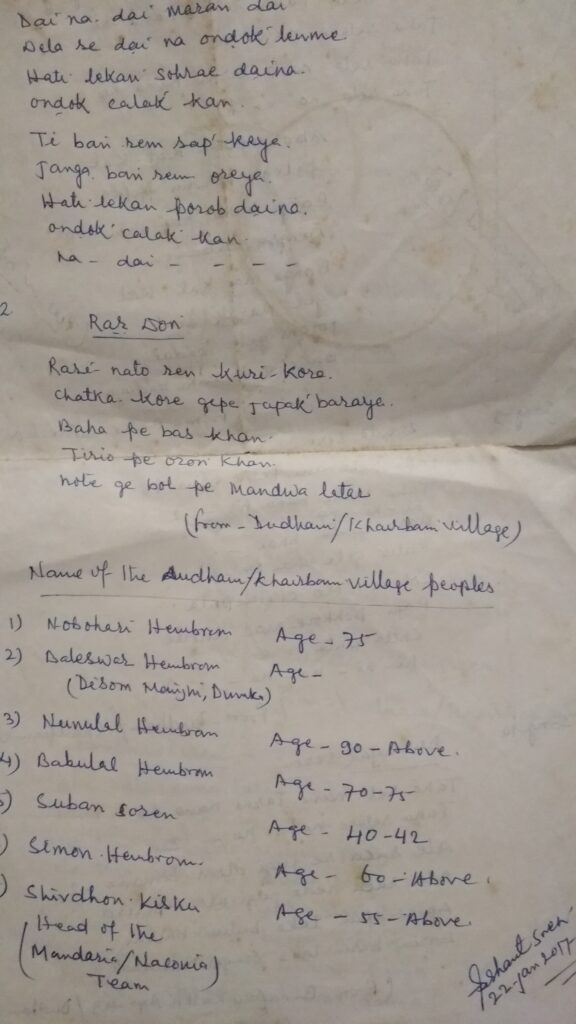

Sushant Soren and some of his field notes.

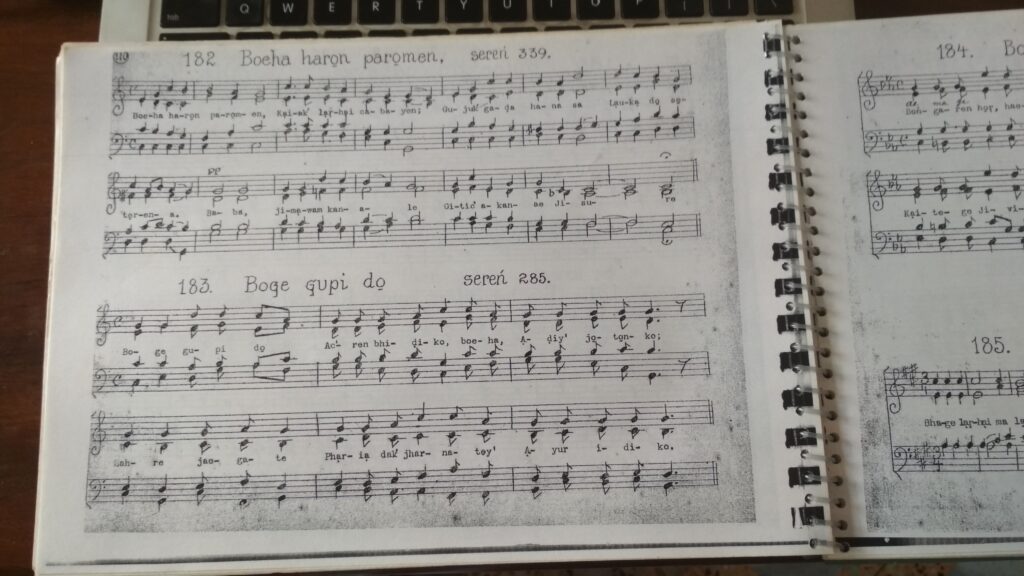

Arnold Bake’s Dumka recordings are of songs ranging from the Santali church song of the good shepherd, composed by the Norwegian missionary Lars Olsen Skrefsrud (Boge gupi do, song 2 of cylinder 1) to the same song sung as a four-part harmony (song 1 of cylinder 2), a do̠ń seren or wedding song about the ‘famine which happened five years ago’ (More serma akal keda, song 3 of cylinder 1). Then there was a flute tune (song 1 of cylinder 1) which the community of listeners in Kairabani Dudhani identified as a melody played during Sika̠r, which is the annual hunt festival—a communal gathering of only men, when disputes are resolved, while there is singing and dancing, food and alcohol through the night. There was also a song about the train (Nawa nawa railga̠di, song 2 of cylinder 7) and a song about Boṅga buru or the nature spirits (Abo manwa kal kal, song 1 of cylinder 6, identified as Sõhãṛe by BLSA, but described as rar danta by the Kairabani Dudhani people).

That morning, we recorded for more than two hours. I am keeping here some short video clips from that session. They were recorded by Sushant Soren (where I am seen) and by me too.

While traditional instruments such as the tirio flute and ḍhud̠ru banam are played in these recordings, sometimes to accompany the song and sometimes as solo pieces, the songs are marked by the absence of percussion. This absence somewhat denaturalises the songs, because Santali songs are essentially about drums, beats and rhythms; the songs are also inseparable from dance. When we were recording in Kairabani Dudhani in 2017, the crowd which had gathered were slowly warming up to the session and finding it fun to listen, talk and sing, and seemed to like the idea of being recorded. The madol player was also there. Before starting a song , they said, there is no madol here. They could distinctly hear, despite the noise of the cylinder. Can we play ours? they asked, much to our embarrassment. As if it was for us to decide.

They brought their drums to the listening session in Kairabani. January 2017. Photo, The Travelling Archive.

Who exactly were the singers Bake recorded in Kairabani? Did they stay in the boarding? This question has kept coming back to me. It troubles me that here are no name for the singers for these archival recordings. ‘There are young boys and older ones, and also adults, who come for training as a village teacher,’ Bake had written in a letter to his mother on 25 March 1931. There is no other detail.

The Kaerabani (Kairabani) School Brass Band visiting Narainpur on 9 March 1931. Standing on the left are David Jha, Bernhard Helland. Muriel Helland and Jakob O. Soren are on the right. The photograph is from the digital library of the University of South California. From the Danmission Photo Archive. CC Attribution (CC BY). https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/ Permanent link: http://doi.org/10.25549/impa-c123-98657

The Norwegian director of the school, Rev. Bernard Helland, and his wife Muriel hosted the Bakes in Kairabani. This is a photo of a photograph from the Arnold Bake Collection, Special Collections, Library of the University of Leiden, taken during my first visit to the library in 2010.

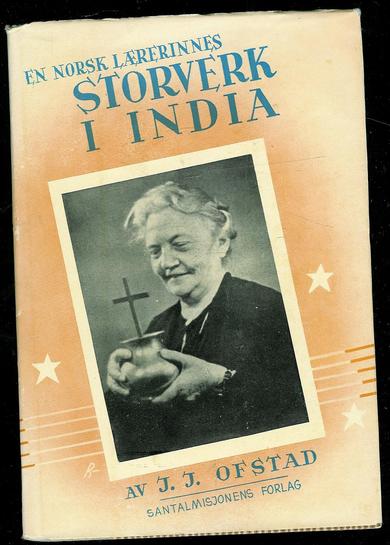

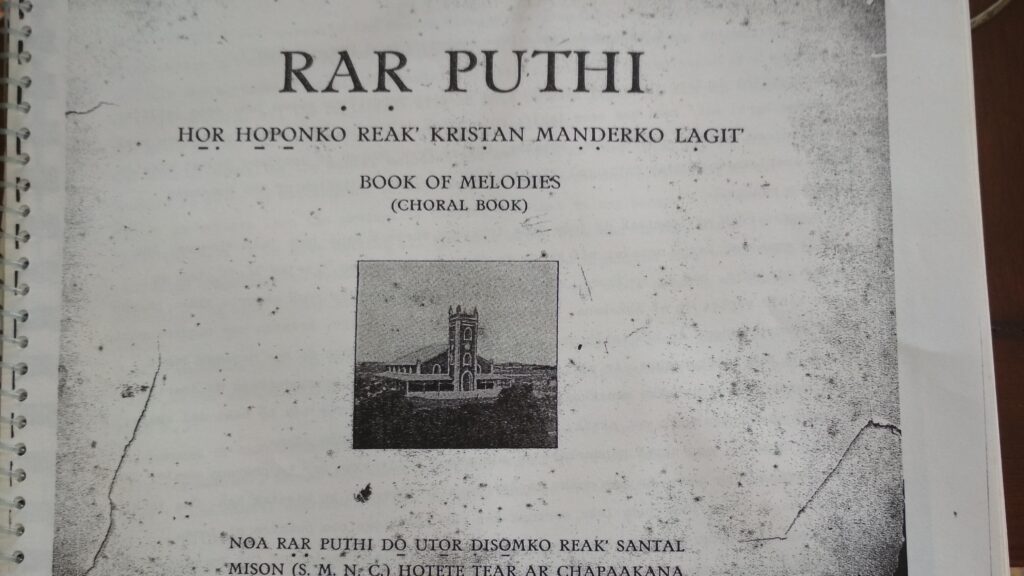

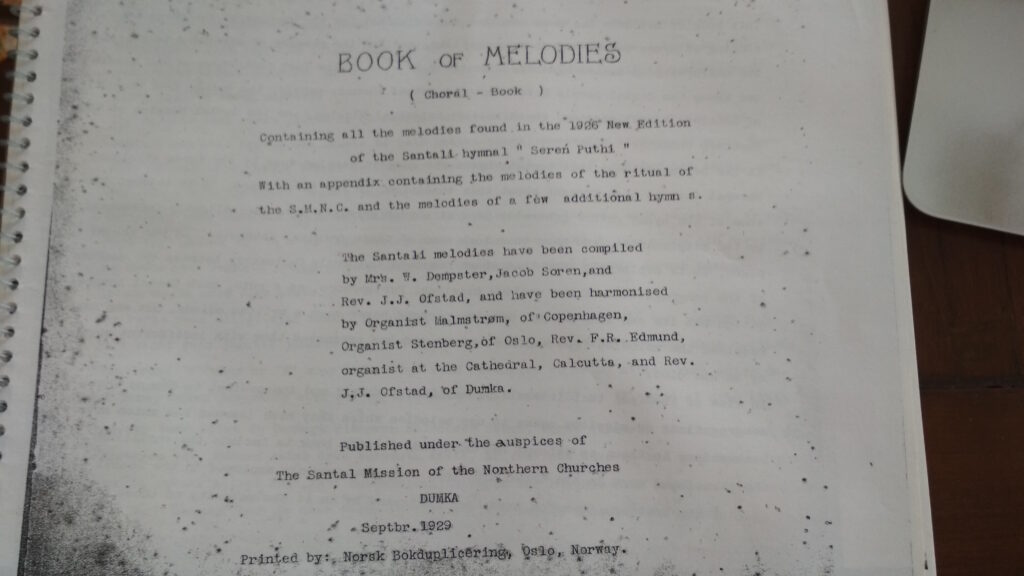

I made inquiries after the Dumka trip to see if there was any way I could have a register which gave the names of the Kairabani singers. After all, they were members of the mission choir. However, for now all I know is that J. J. Ofstad (Rev. Johan Johansen) was the music teacher of the school, Jacob Soren was his Santal assistant. I believe that Ofstad wrote a booklet about the Kairabani Mission, perhaps it has some names, but I have not had the opportunity to see it. All I have seen are the song books Seren Puthi and Rar Puthi. On 24 January 2017, we had gone to Jamuasol near Dumka to meet Mathias Hansda, who was a student of Kairabani High School for eleven years from 1951 and later became a teacher. He was also a member of the school’s brass band. He could fill in some details about the school and the practice of music; the school’s music teacher was Benjamin Murmu, who was a student of Jacob Soren, who in turn was a student of J. J. Ofstad. But he did not have any specific information about the singers, perhaps I could contact Benjamin Murmu’s daughter, Gloria, he suggested. That is as far as I have been able to get in my search for names, which is not saying much, I am afraid. But the important thing about research is also the questions, I think. Someone else can then try to answer them, if we can’t.

Mathias Hansda reminisced about his days in the Kairabani Mission school, as a student and teacher, about the school band, his teacher Benjamin Murmu, listened to the recordings, sang a little bit and talked about how things change over time, through rahan-sahan; that is, in the course of one’s life. This is a short clip from that conversation, in Hindi. 24 January 2017. Photo: The Travelling Archive.

En norsk lærerinnes storverk i India (A Norwegian Teacher’s Great Work in India), by J. J. Ofstad (1879-1963)

Before visiting Mathias Hansda, that morning on 24 January 2017, we had been to the NELC radio station in Bandorjori, Dumka, from where they broadcast church-related programmes in Santali. The Northern Evangelical Lutheran Church (NELC) in Dumka is the successor of the Santal Mission of the Northern Churches. Mathias Hansda also mentioned the NELC radio station, which used to be run by the American missionary, Naomi Torkelson. A radio station, even if it is set up for the purpose of spreading the faith, will have sonic records of history, just as Arnold Bake’s cylinder recordings from Dumka are also a record in sound of a time.

On the wall of the NELC recording studio in Bandorjori, Dumka hung a photograph of Lars Olsen Skrefsrud, the Norwegian missionary who had composed the song of the good shepherd, ‘Boge gupi do’, which Bake had recorded. Photographs: The Travelling Archive, 2017.

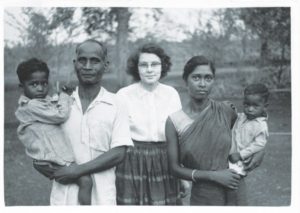

What drove a young woman all the way from Ohio to the Santal Parganas and what kept her stationed there for decades? I arrived at these images from the sounds of Arnold Bake’s cylinders. The photographs provoke such questions and the answer is never simple. The more I have delved into Arnold Bake’s Santal recordings, the more inadequate I have felt while also knowing that here lay a vast site worthy of long-term excavation. The photograph on the left is from the Danish Santal Mission or DSM’s annual meeting in Nyborg, 1986, where the American Missionary Naomi Torkelson (right), secretary of NELC, is seen speaking to the audience, with Rev. Inger Krogh Nielsen translating. The photograph is from the digital library of the University of South California. Source: Danmission Photo Archive. CC Attribution (CC BY). https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/ Permanent link: http://doi.org/10.25549/impa-c123-99919. The photograph on the right, which I sourced from the internet, can be shredded and each strand separately analysed. Who are the people in it? What is Naomi’s relation to them?

The photo on the right is as thought=provoking as as some of the songs Bake recorded; they led to so much debate and discussion. Take the song ‘Boge gupi do’. In Kairabani Dudhani, the listeners could not really engage with the song. That is a church song they said, listened once, listened again and got busy talking among themselves and then they said they did not know what song it was. So, we moved on to the next song. In Johar Human Resource Development Centre in Dumka, on the evening of 22 January 2017, a group of artists and intellectuals sat in a circle and listened to Bake’s recordings, and they were led into the discussion by Father Solomon. They were all connected with Johar and all of them were possibly church-going Christians. Their connection with the song was immediate.

Listening to Boge gupi do in Kairabani. Recording by Sukanta Majumdar.

In Johar, we sat in a meeting with a group of Santali intellectuals and artistes, including singer Babita Murmu, Sebastian Soren, musician, Emanuel Soren, social actvist, Bijoy Tudu, government officer, Suleman Marandi, teacher, Sanatan Murmu, bank manager and others; Father Solomon, a Tamil who spoke many languages with great ease, navigated the course of the listening session. There were more nuanced debates here on the significance of words, form of song, slight regional variations of style.

Boge gupi do at Johar. The listeners immediately connected with the song.

Pages from J. J. Ofstad’s Rar Puthi: Book of Melodies (Dumka: The Santal Mission of the Northern Churches, 1929), including the song Boge gupi do. We got a copy of the book from NELC.

While the church was taking root among the Santals, songs and rituals and local knowledge were also getting recorded for posterity.

There was a song the listeners of Kaiarabani Dudhani sang for us, ‘Ot́ma lo̠lo̠’ (song 3, cylinder 4), which is sung during Dasãe. Rev. P. O. Bodding, in his Studies in Santal Medicine and Connected Folklore (Kolkata: The Asiatic Society, first published in 1925), wrote in detail about the annual Dasãe festival in the month of the Dasãe or Ashwin, which is also the time of the Hindu festival of Durga puja. ‘This is naturally not a Santal festival; it is celebrated by the many Bengalis living in the country, the Santals participating as active spectators.’ Bodding wrote about young Santals going to see the idols and ‘sometimes [they are] even hired to carry it [the idol].’ This is the annual festival which marks the end of a three-month training the ojha or guru, the master medicine-man who knows all about plants, medicine and healing, has given to his all-male students. The festival marks this passing down of knowledge, as the young men and their teacher, dressed in kạcni (kind of skirt) instead of the ordinary ḍeṅganak’, or loincloth, and wearing turbans (there are aspects of cross-dressing here), carrying peacock feathers and the musical instruments buan and kabkubi, go wandering through villages, singing and dancing, gathering food from the people for the feast later in the evening.’

Page from Bodding’s book

The day after we went to Kairabani, on 23 January 2017, we went to Harinsingha, a village also in Dumka.

Sushant Soren, Habil Murmu and Aruna Hembrom, all Johar Human Resource Development Centre staff, took us to Harinsingha, where they run advocacy projects, making people aware of their deprivations and the rights they are entitled to, and help them fight for those. This village was very different from Kairabani Dudhani. Things were far more in order, organised, and the people seemed also economically better off. Many men and women had gathered in the house of village jo̠g ma̠ńjhi (community leader) Motilal Murmu; they had brought their children along. The women were beautifully dressed for a special day, in their traditional green two-piece saris. The courtyard was teeming with life. This was clearly a village where they were taking special care to reclaim their heritage, they had songbooks, practiced music and dance, and thus they were also especially interested in the songs we had brought with us. It felt like there was a kind of cultural revivalism going on here, as the women washed our feet first while we sat on chairs; they said that is how guests are treated in their culture, while I felt that in order to be the good guest and good researcher, I was having to throw all class, caste and gender consciousness to the winds. (I am glad I haven’t had many such experiences over my decades of fieldwork.)

If we listen to the Harinsingha listeners’ response to the railgadi (locomotive) song that Arnold Bake had recorded (Bake India I, Song 2 Cylinder 7), we will be able to hear the confidence in their voices and preparedness.

Kolgadi calak acte’ge sung by the villagers of Harinsingha, Dumka

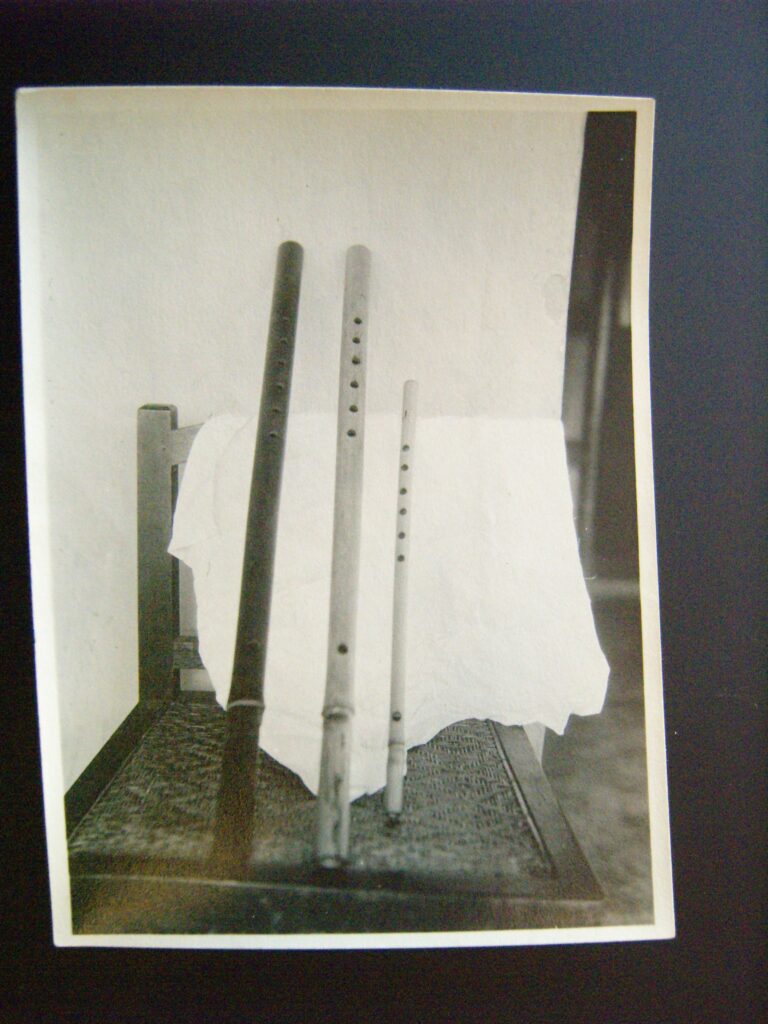

In his 1937 essay, ‘Indian Folk-Music’, published in Proceedings of the Musical Association 63 (1936-1937), Arnold Bake had written of the Santals, ‘an aboriginal tribe of Munda stock which inhabits the hilly country on the borders of Behar and Bengal in the middle South-east’, that these people, ‘agriculturists where they have not flocked away to rice-mills or railway stations in which they work as labourers, are great hunters with bow and arrow. Even when living amongst the Bengalis where there is no hunting to be done, the men are very often seen carrying bows and arrows, Next to the drum, their beloved instrument, is the bamboo flute of unequal length with six holes. They often use their flutes as walking sticks and once I saw a combination of flute and stringed instrument where a Santal had fixed one string along the length of his flute and used that after the fashion of religious beggars to give the drone to his songs. This however was definitely an innovation not belonging to Santal music proper. They have preserved their independence of language, religion and music through decades of close contact with Bengalis and it is only under mission influence that they are now changing all of these, It was a sad experience to hear them sing their changed folk-melodies, in four parts, to religious words after the fashion of our hymns. The fact that their music has not reached the melodic perfection of Hindu India apparently makes them take to part-singing with greater ease than I have noticed anywhere else in India.’ Much prejudice in this remark, ideas of cultural evolution at work, but here in this video, the listener-performers of Harinsingha were demonstrating how a certain flute is made and how it works, to the great amusement of others.

Arnold Bake spent time measuring the distance between the holes in the Santal flute and sent his measurements to the archive in Berlin. On 15 April 1931, he wrote to the director, Austrian ethnomusicologist Erich M. von Hornbostel, ‘I include here two pictures of the Santal instruments, flute (which I have here) and banam. I will take pictures of the drums later. The drum is the most important. The flutes are always made in pairs. The two big ones are a pair. I will send you the measurements:

Length (of the great flutes, which are exactly the same) 72 cm

Thick (measured in a circle) 10 cm

Average (Outside Dimension)

Average (internal dimension) 22 millimetres

Length (up to the knot of the bamboo) 12 Ω cm

Length (up to the middle of the blow hole) 18 // 4 cm

Removal of the first finger hole from the blow hole 25 cm…’ (Translation from the German original by Debjani Das. Letters kept at the Berlin Phonogramm-Archiv, copies of which were kindly given by Professor Lars von Koch)

Photos of photos which I took while studying the Arnold Bake Collection at Special Collections, Library of the University of Leiden in 2015.

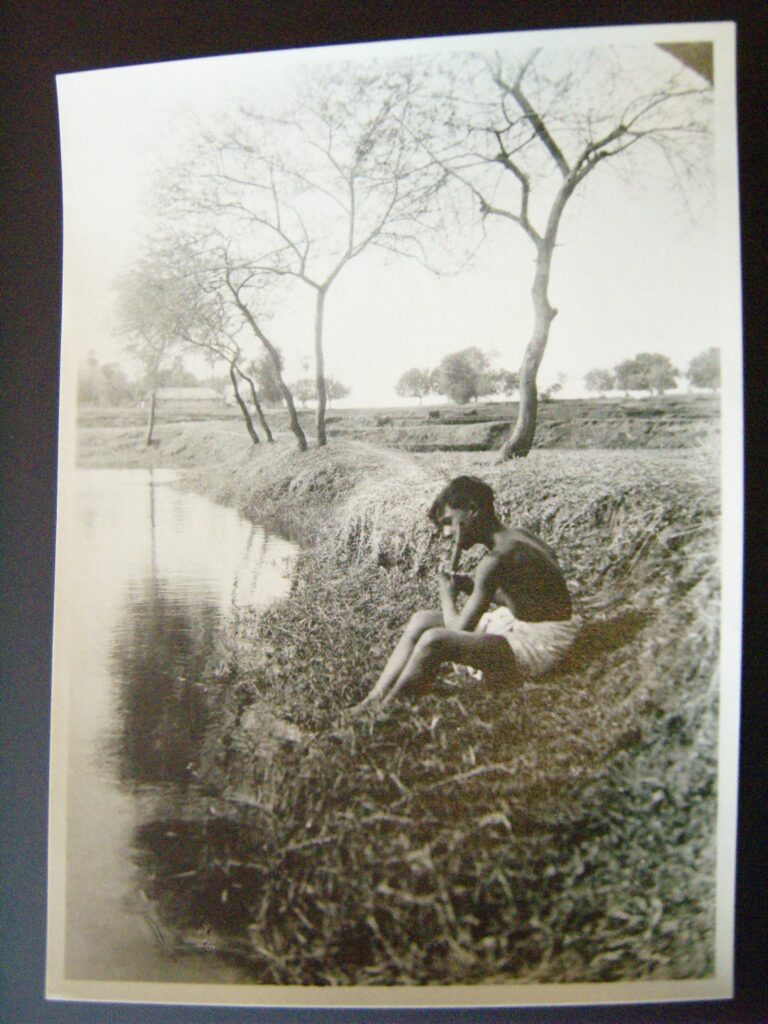

On the first day, when we met artistes and intellectuals at Johar in the evening, as we were playing Bake’s Santal recordings, they listened to the first flute of the fourth cylinder and responded with a beautiful song about the jugi, who goes from house to house gathering alms in exchange for telling people about their forefathers, even showing them their ancestors’ face. That song is in our recording session note for that trip in 2017, Babita sang it a second time for us to record better, coming closer to Sukanta’s microphone. ‘The jugi or traveller has come visiting, and the poet requests him to show the face of his dead parents. Show me my parents’ face, because after death, they have become faceless. How will I see their “roop”, how will I get their love?’ They explained the song to us and told us about ‘jong baha’, the ritual of floating the ashes of the dead. In a sense, Bake’s cylinder recordings are like the ‘jugi’; they have the power to show us the ancestor’s face.

Nunulal Hembrom, more than 90 years old in 2017, walks back after our listening/recording session in Kairabani. I do not know where he is now. Photo: The Travelling Archive.

Postscript

My friend and longtime collaborator, musician Satyaki Banerjee, shared a video with me, some time in May 2022. A friend of his, Sukrit, had recorded it when he went to a workshop on Adibasi (indigenous people) dance in Tepantar Theatre Village in the border of Birbhum and Barddhaman. I was quite startled to see it. There was someone playing a flute of the kind the listeners of Kairabani were describing to us (see video above). This seemed to me to be that flute with two parts. Sukrit wrote to Satyaki that the man with a hibiscus in his ear is Subal Hembram, he makes his own flute, which is supposedly called the ‘chyng murli’. He plays for himself, just like that.

Sukrit’s message to Satyaki: ‘Ami 11mile er tepaantar e ekta adibasi nacher kormoshalay chilam bigoto der mas, eta sune khub valo legechilo, tai tomake pathalam. Olpo olpo bujhi, je mul harmony ta lead korche tar nam mungli di, onake jigges korle valo bolte parbe. Eta bodhoy biyer gaan […] tumi chaile tomar satheo kakhono alaap koriye debo, manush gulo koto sundor, churaanto aesthetic. Hyaa go, nijer monei bajiye Jay, etar nam naki chyng murli, r ek kaane jobar dnati kaner fnuto diye dhokano, odbhut ei lok ta satyaki da. Ei jontro ta enari nijer haater banano, subal hembram.‘