The Bauls of Kenduli in 1932

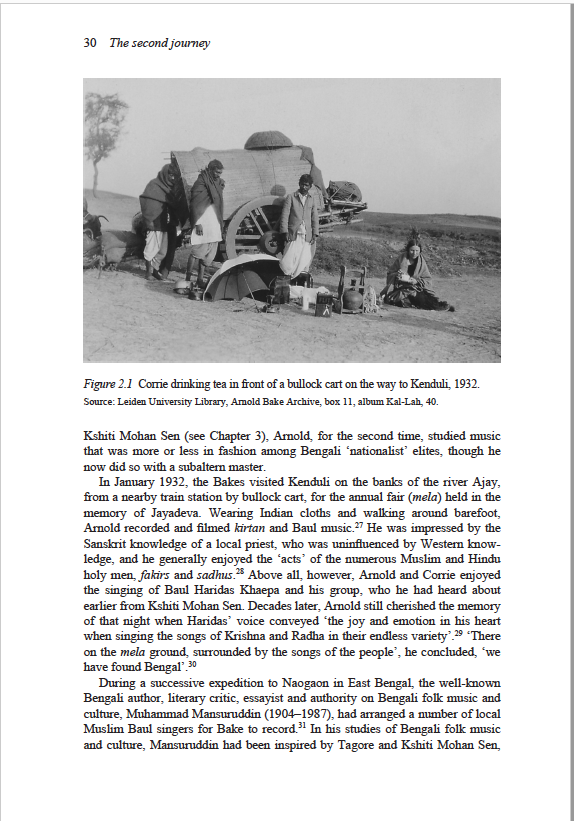

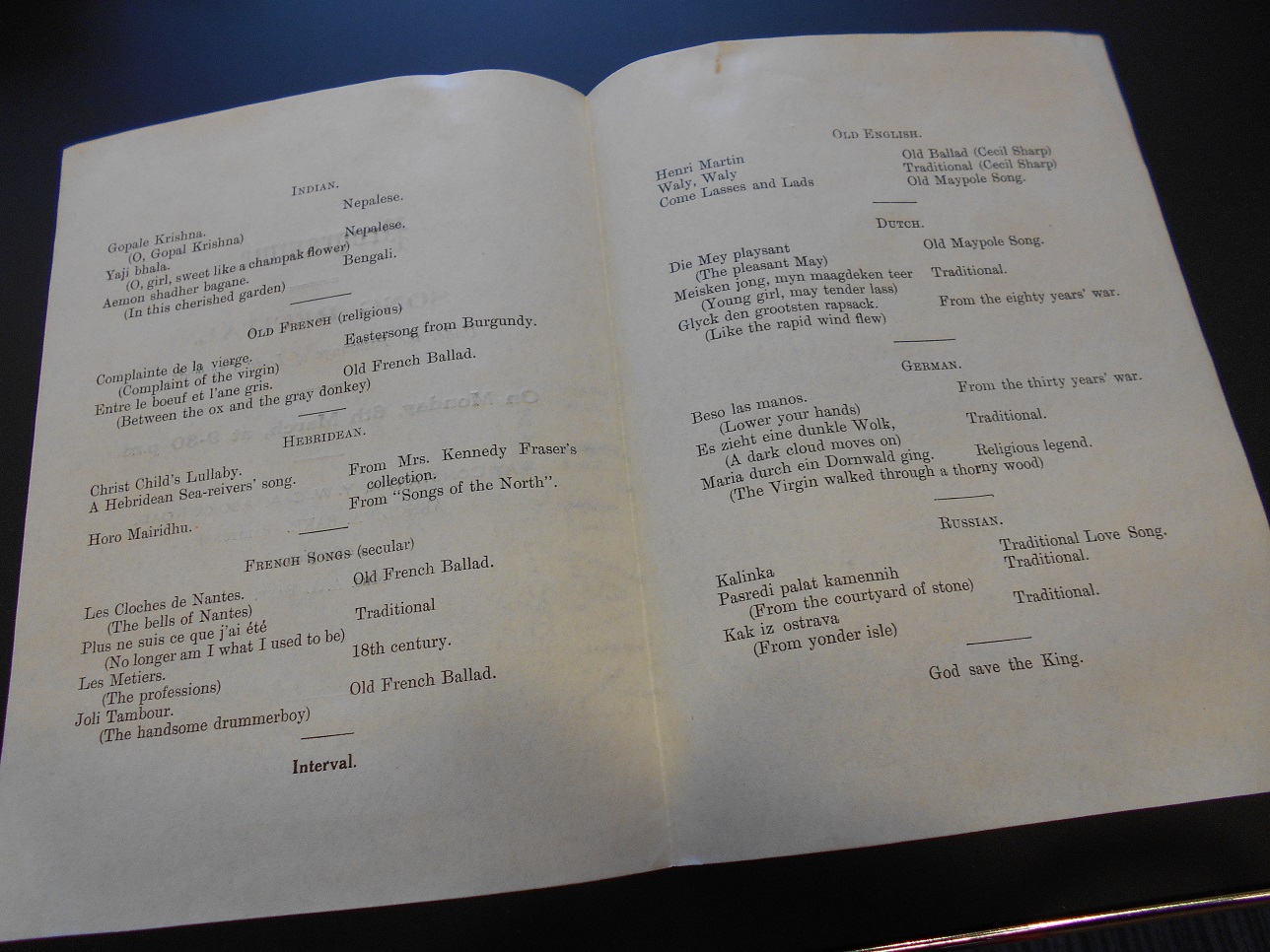

This was that trip to the festival of the bauls that Arnold Bake had been planning with Kshitimohan Sen ever since he came to Santiniketan for the first time in 1925 and since he began to learn about baulgaan. He did not go on this trip with Kshitimohan, however, but with Gurusaday Dutt, the district magistrate of Birbhum. He wrote long letters to his mother on 12 and 20 January 1932, the first one about preparing for the trip and the second about their experiences in Kenduli, recording kirtan and baul. The bauls he names in his recordings from 15 January 1932—Bake India II cylinders 103-06 and 109—are Haridas Khaepa, Murali Das, Krishnaballav and Acintadashi.

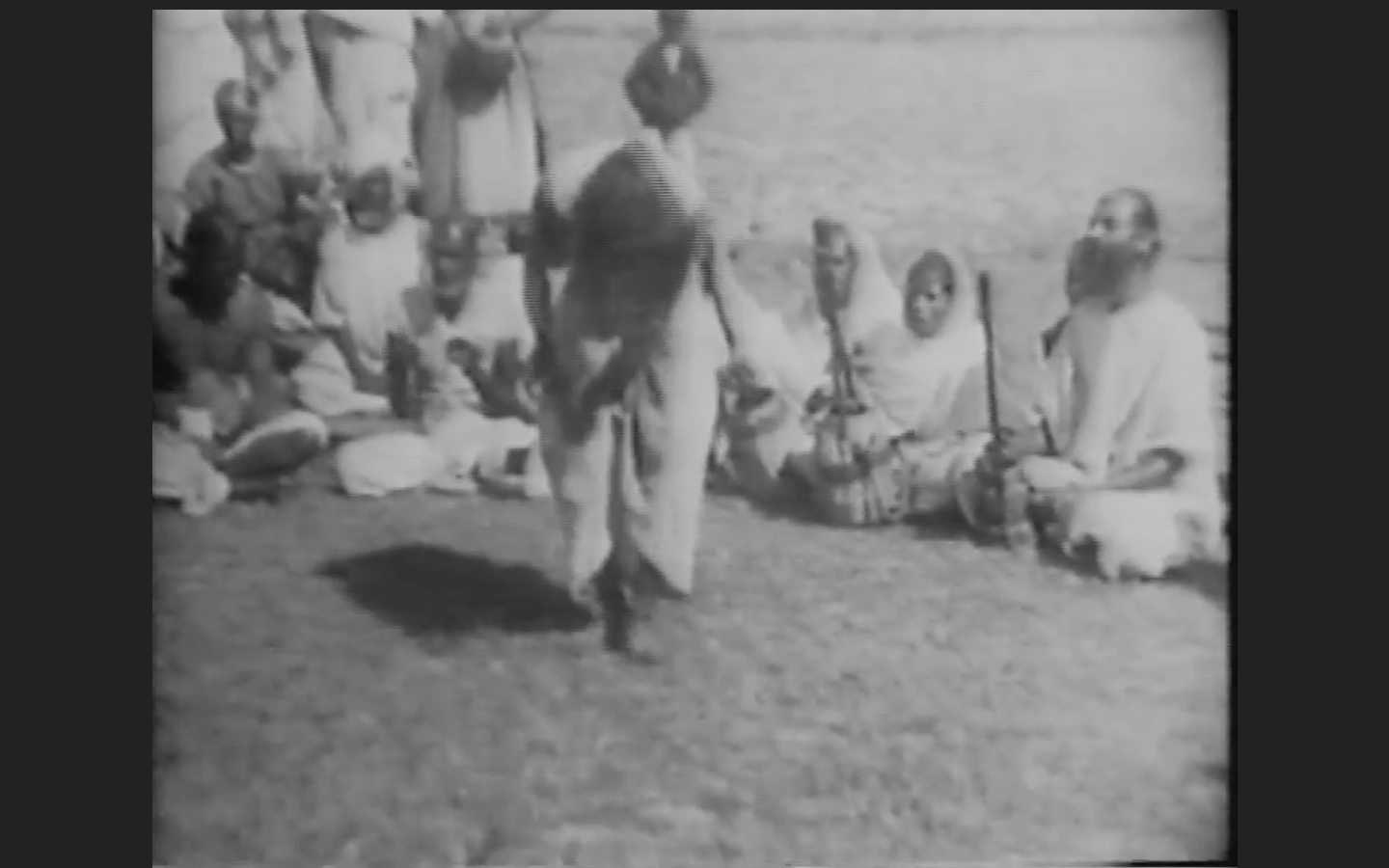

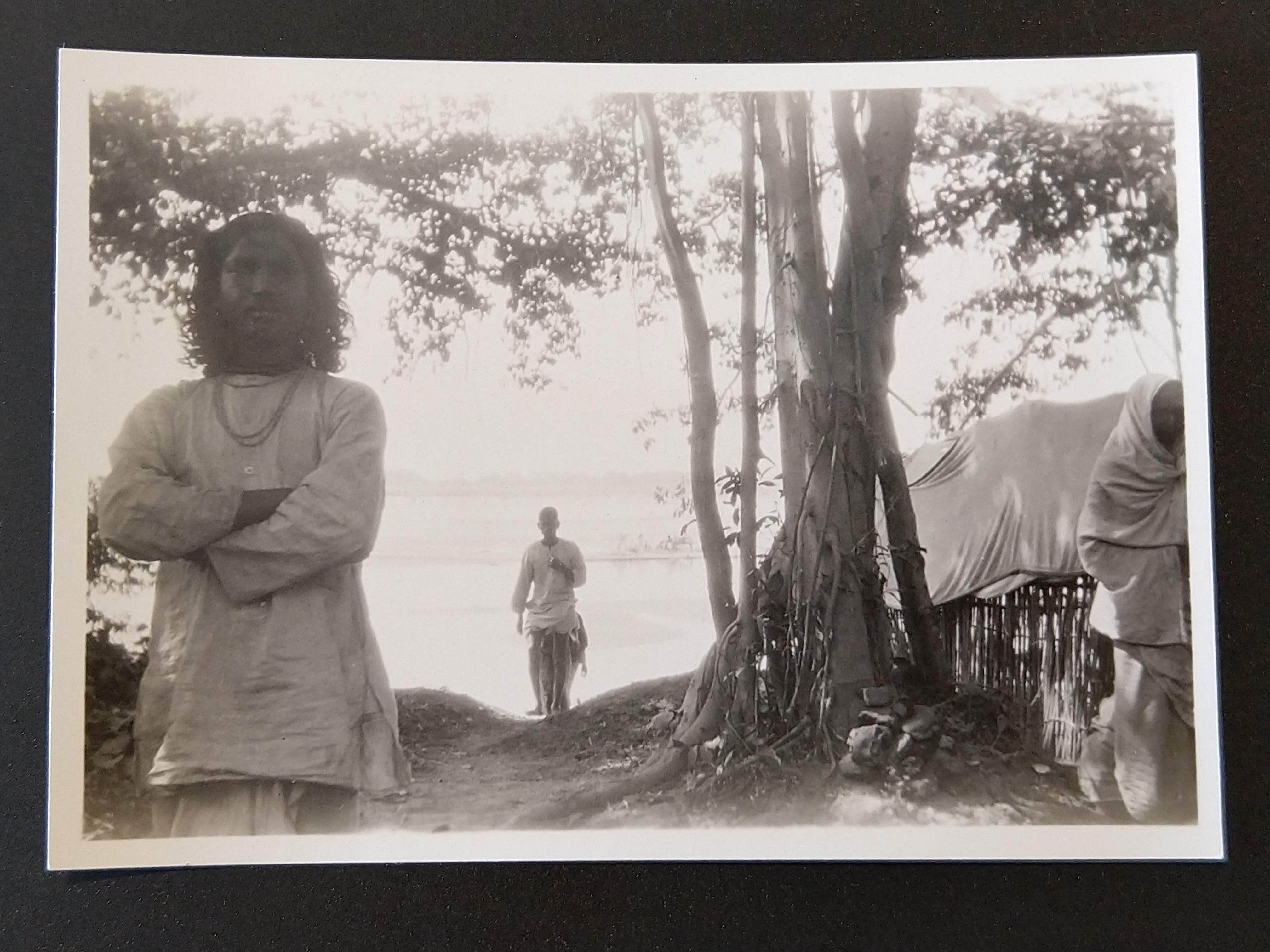

Stills from Arnold Bake’s Kenduli footage. Source: Archives and Research Centre for Ethnomusicology, American Institute of Indian Studies, Gurgaon.

I do not have any audio material or video recordings of my own to add to this archive, because when I shared the songs with experienced practitioners of this music such as Debdas Baul and Parvathy Baul and they shared the songs with others, none has so far (July 2021) been able to identify the songs with certainty. Hence my attempts at writing down the words have remained unfinished. I tried to notate the songs too. But I could not get too far. Here are some scribbles from my notebooks. Just to keep a record of the process of an unfinished work. The recordings per se are extremely important as they come out of a time when Kenduli was still very much an insider’s experience—by ‘insider’ I mean insider to the practice, faith and way of life. Not all bauls of course. The listener, the villager who came and bought things at the fair, those who came to bathe in the waters of the Ajay—they were the insiders then. Bake and people like him would be rare in Kenduli at the time. That does not mean of course that it was not crowded. The Films of Bake on this website, uploaded more than ten years ago when my knowledge on Bake and Bengal was even more tentative than now, show scenes from the Kenduli mela in 1932.

Pages from my notebook, 2021

Jan-Sijmen Zwarts, the young Dutch student of Utrecht University, who had come to stay with me in 2016 and 2017, and help me work with the Arnold Bake letters I had photographed at Leiden the previous year, summarised the content of the letters Bake wrote to his mother about Kenduli and it is something like reading pages of a diary (I have retained the spellings in the letters).

12 January 1932. Bake will leave for Kenduli after writing this letter. He wonders if it will be interesting. Mr. Datta himself will be there, too. Bake says that it will be nice to see him, but he thinks his enthusiasm might drive the bauls to madness.

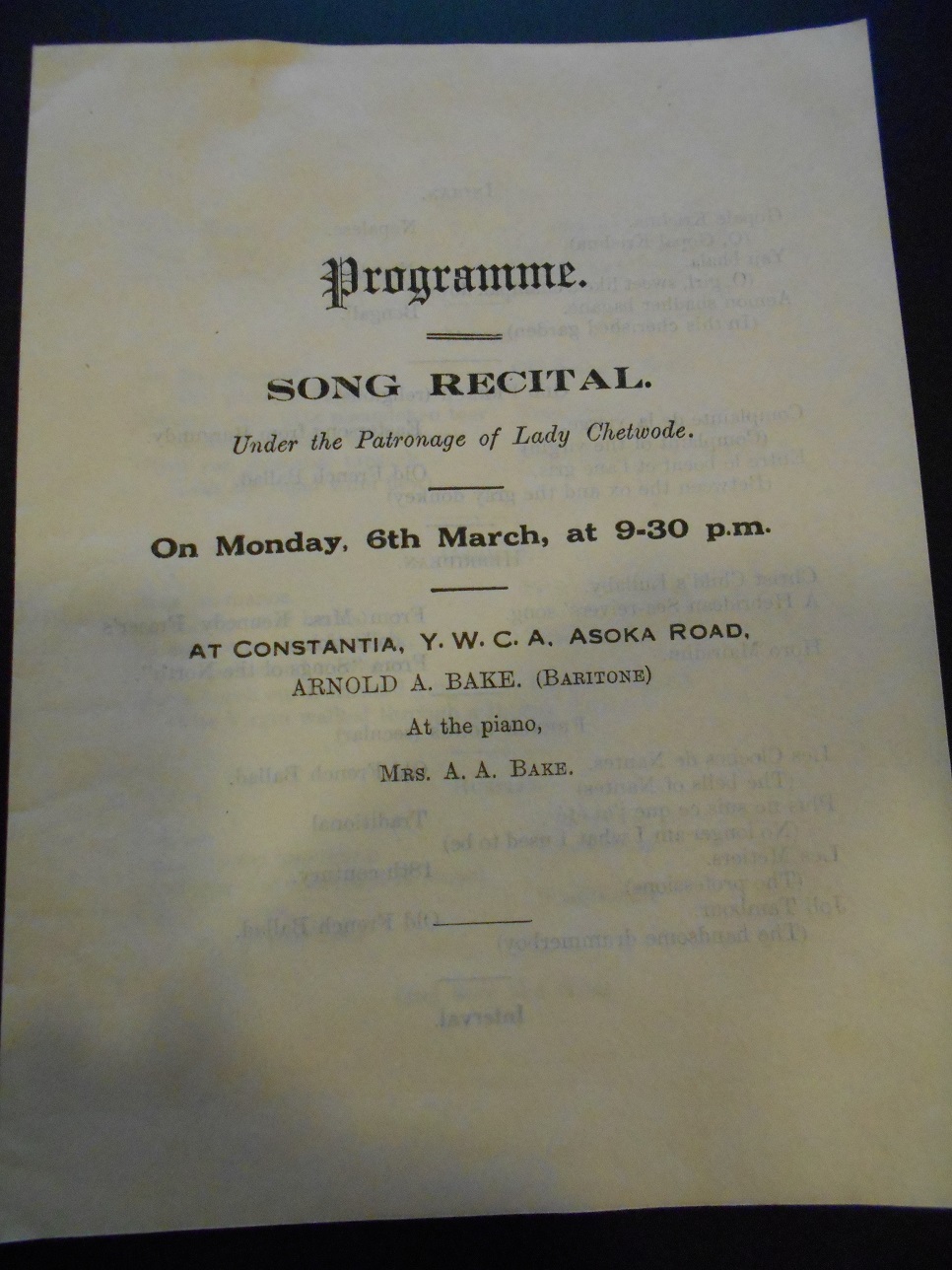

Bake mentions that before going on a concert tour in March he wants to do two things: see the warriors’ dance in the Dumka Hills and visit Naogaon for baul songs.

20 January 1932. Bake has been to Kenduli and they had the most amazing time – even though he was not expecting too much after Khiti Mohan Sen telling him that nowadays it’s not really worth going there anymore.

The mela was at least three times bigger than the largest he’d ever seen before.

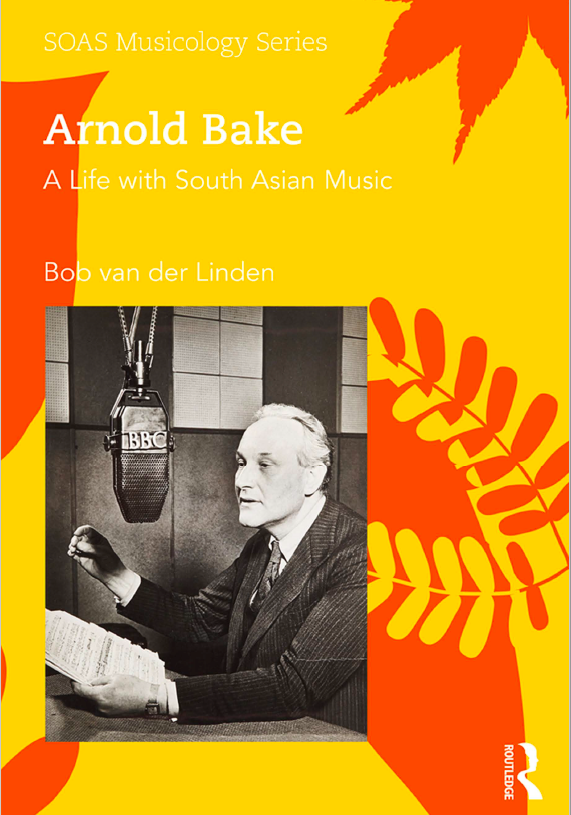

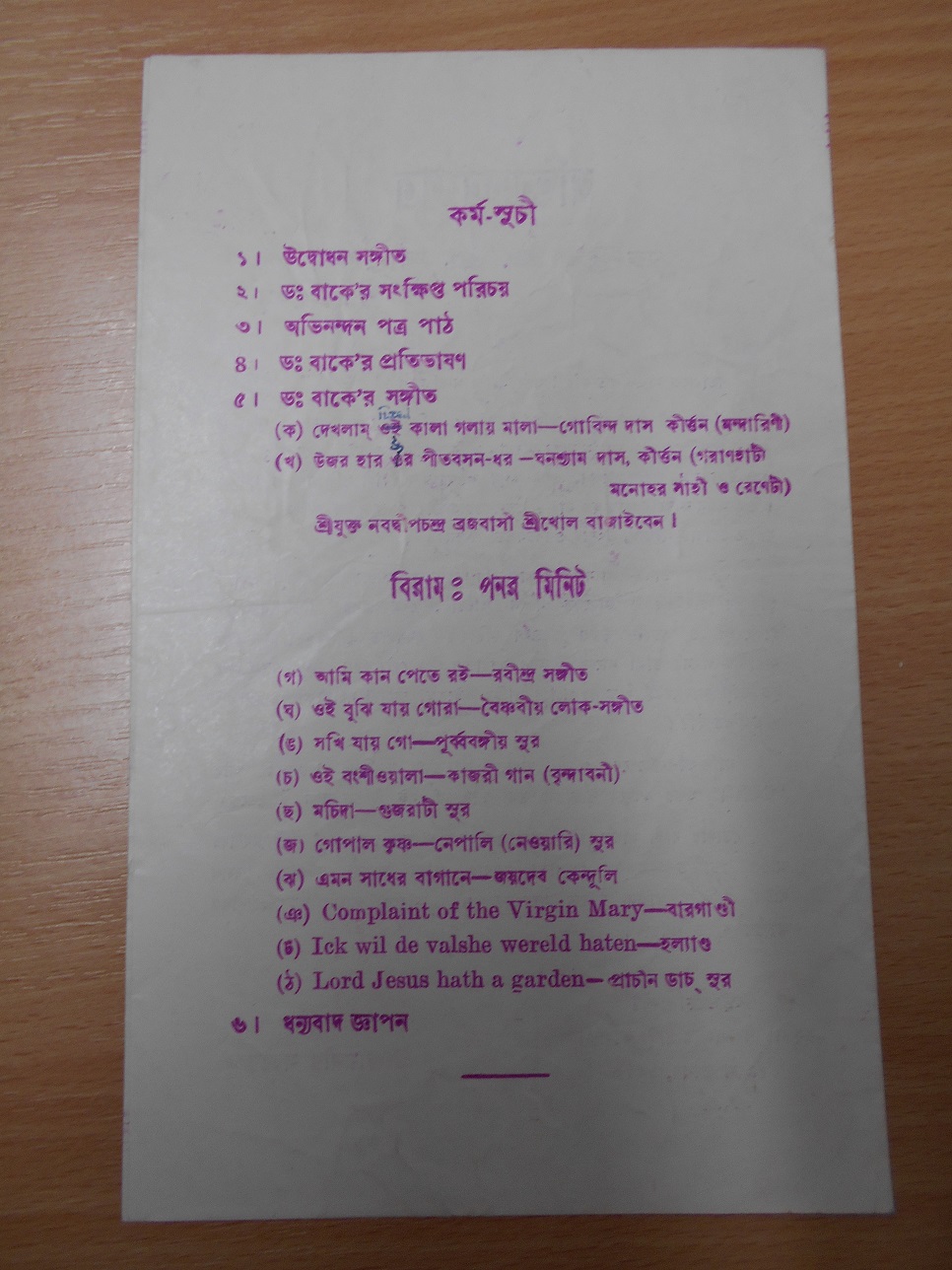

Cover and a page from Bob van der Linden’s Arnold Bake: A Life with South Asian Music (2018).

Bake meets a very friendly sadhu when making his way to the mela from his camping site. The man shows him the sunset from a nice place, and then takes him to the place where the bauls and their companions are staying. There is a huge banyan tree just outside of the village where all kinds of ‘freaks and outsiders’ have made their camp.

The villagers are very hospitable when showing Bake the temple. He is allowed to enter and get very close to the idols. Just then Datta shows up. A number of dances are performed in Datta’s honour, and three bauls play some music – other than that, the first evening is not very special.

The high priest promises to arrange a recital of Jayadeva’s Gitagovinda. Jayadeva was born in Kenduli.

Bake comments that there was a large number of women present at the mela, who were surprised to see Kees in a sari. He also notices that being dressed as an Indian causes the locals to speak freely, something Bake thinks would not have happened if he’d looked like a ‘sahib in English clothes’.

There is also a large number of fakirs. One of them sat on a bed of nails, another had held his arm straight up for twenty years. Bake comments however that this ‘entertainment’ is not what makes a mela interesting. What makes visiting a mela worthwhile, according to Bake, is the devotion, bathing in the river, visiting the temple and having the texts recited, and the gatherings of sadhus beneath the banyan tree.

As if from a film. Kenduli 1932. Source: Arnold Bake Collection, Special Collections, Leiden University Library. (Photo of photo, by me)

It was difficult to find ‘good’ bauls. Many people who invited him to listen to their music were only mediocre, says Bake. He was starting to feel a little desperate but comforted himself with the thought that he would only start recording the next day, so there was still time.

After dinner, the group (now in company of several others from Santiniketan) make their way to the temple. The ceremony starts with a seemingly endless stream of namsankirtan performances. Bake, Kees, and Charley make their escape from the rest of the group and Mr. Datta to investigate a small group of men and women who made their camp a little further from the tree. They find a man by the fire playing the bamboo flute, and his music is otherworldly, so good. When the flute player was finished another man sang a song, which was really beautiful too. Bake is very pleased and overjoyed to hear that the men would be happy to come to his tent the next day to be recorded. The flute player’s name was Hari Das.

The next day, Bake meets a woman, Ms. Sen, who is looking for Hari Das, because according to Khiti he is the only one worth listening to at the mela. Hearing this makes Bake proud of the fact that he already discovered him as being such.

At the temple Bake tries to do some recording. It proves difficult because the leader of the singers has a weak voice. He mentions that he can afford to experiment a little, because he can just scrape clean the cylinders that turn out badly. It takes longer than he expected, and Bake is only able to head back to his tent by half past 5. He finds Hari Das and a number of others already waiting for him. Despite the slight delay he succeeds at recording everything he wants.

The next day Bake meets Hari Das another time in the evening. This time he also has a chance to meet his 120-year-old guru. Hari Das agrees to teach Bake some of his songs, much to Bake’s delight. This final meeting concludes Bake’s time in Kenduli.

Arnold Bake had learned the song ‘Sadher bagane’ which was sung by Krishnaballav and was recorded on Bake India II, cylinder 105. He would perform it as ‘In the cherished garden’, in concerts. Source: Arnold Bake Collection, Special Collections, Leiden University Library.

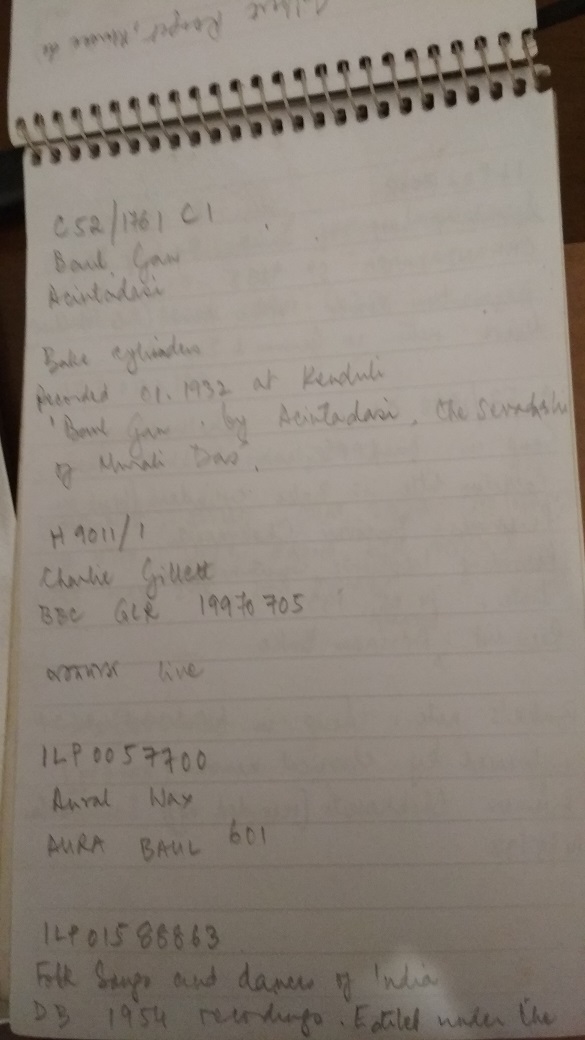

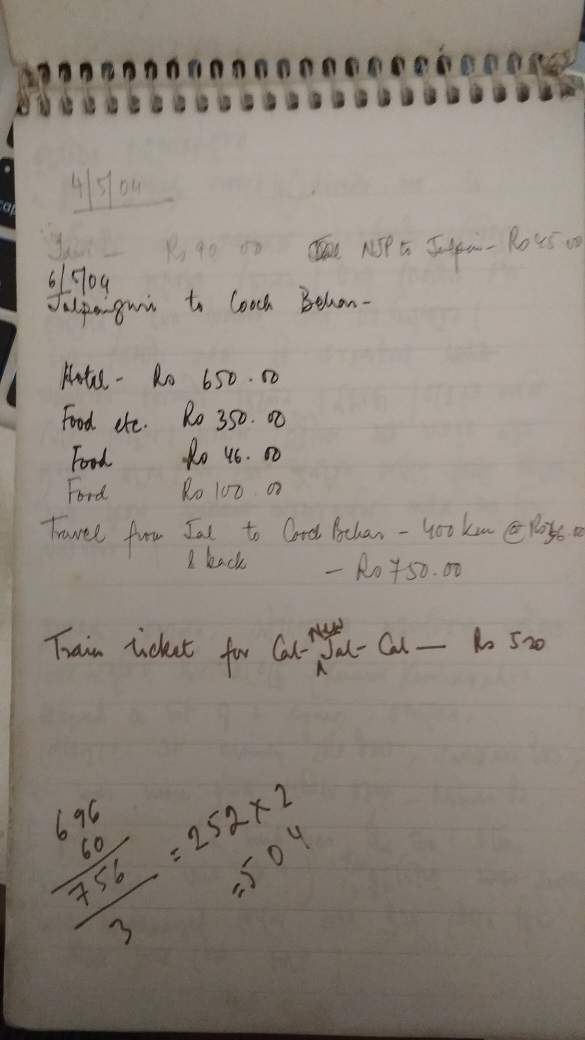

Pages from my notebook of 2004.

Personally, I have a very special connection with these baul recordings of Arnold Bake. Way back in 2004, when I was working in the British Library, looking through the catalogue, listening to this and that, taking random notes, I had come across three things which struck me. Kenduli, Acintadashi, sevadashi of Murali Das and baul. The catalogue gave the recording date as 1932. At that time I had no idea what a cylinder recording was or who Arnold Adriaan Bake might be. But a recording from Kenduli in 1932 was reason enough for me to stop and think. In a sense, my Bake research grows out of that seed.

Here is that recording. Bake India II, cylinder 109. I had it from the Berlin Phonogramm-Archiv, of course, but also from ARCE, as far as I remember (I requisitioned the ARCE recordings too long ago, in 2009).

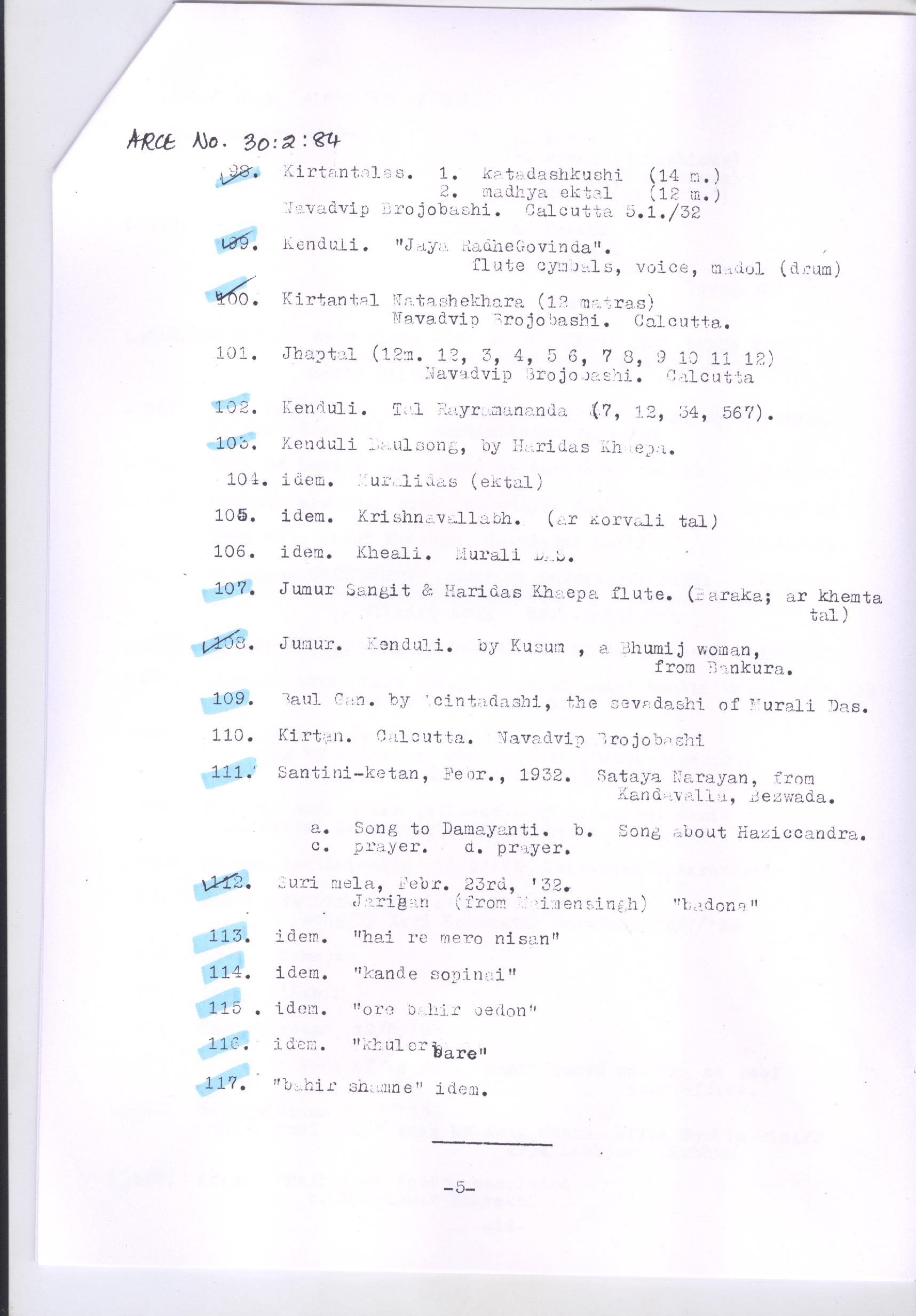

Page from the Bake cylinders catalogue of the Archives and Research Center for Ethnomusicology (ARCE), Gurgaon, India.

Now after almost 20 years, when I have acquired some experience of listening to wax cylinder recordings and can sense the voice flowing under the ground of noise, I can hear two things in this song. I implore the listener to listen with headphones and to listen again and again. Firstly, you will listen to a dubki and you will hear a voice joining the main voice after the first line. I assume this voice to be Murali Das’s, because they were partners and so they would have sung together. And I assume he was playing the dubki, standing next to her, she was mainly facing the funnel of the phonograph, he was to her side. I can picture this. And I see the women in Bake’s baul film, and think Acintadashi would be one of them, or one like them. And one of the men standing around would be Murali Das. And I think, this Acintadashi, sevadashi of Murali Das—they were names on a catalogue to me and when I finally heard the two voices coming together in the recording, it became a moment of jugal milan for me, a moment of ultimate union.

Secondly, the other thing is the text of the song Acintadashi is singing. ‘Sundaro hridiranjana guru’ it begins. I cannot get all the words, but the song is in the voice of Radha, there is mention of the river Jamuna and she complains about her sufferings for love. She’s lost both shores—e kul and o kul, both. She wants Krishna, her beautiful lover, to take her across the river. The tune is very typically of Bangla kirtan. I wonder about Rabindranath’s composition of 1901 ‘Sundaro hridiranjana tumi’. Although different in tone and temperament, the connection seems quite obvious. I wonder if an existing kirtan might have been at the back of Rabindranath’s creation.

- Laksmisvar Sinha, a Doorway to Many Worlds

- Imam Bux Boyati of Mymensingh at Gurusaday Dutt’s Suri Mela

- Motru Sen and Jaya Tagore: From Image to Sound

- Mapara’s Cradle Song and Shruthi Vishwanath’s Response

- Pinakin Trivedi and the Autograph Book

- Roof-Making Songs of Baori Women

- Listening to Savitiri Govind with Sumana Chandrasekhar

- From Ranjan Shaha to Kobiyal Akhtar Shah in Kasba, Birbhum

- Kusum, the Nachni and her Jhumur

- From Gurudayal Malik to Mohan Singh Khangura and Madangopal Singh