Thanks for giving opportunity to get these valuable information.

Kolkata. 4 September 2019. Purnadas on Nabani Das Baul

Conversation with Purnadas Baul

On 29 October 2018, I was at the British Library sitting at the desk of Lead Curator of World and Traditional Music, Dr Janet Topp-Fargion, looking at some papers relating to Arnold Bake, the Dutch scholar of Sanskrit and Indian music, pioneer field recordist in the Indian Subcontinent in the 1930s and 40s, for my ongoing research on his wax cylinders from Bengal. They gave me a few files with miscellaneous papers and after I finished going through what I had gone to study, namely the typed up sheets of the first catalogue notes for the cylinders, I continued to browse through the other papers, for they looked interesting enough to me. I was allowed to take photos of the papers with my phone and occasionally I found something to bring back with me. Then, I found a few typed sheets stuck together with a pin, with the heading: ‘Overseas Research Leave, Report by Dr A. A. Bake, Reader in Sanskrit. India and Nepal– May 1955 to August 1956.’ This was Arnold Bake’s last trip to India (and Nepal). I was curious, as I knew of two recordings of Tagore songs that he had made in this time, one of Indira Devi Chaudhurani in Santiniketan and another of the Tagore singer Chitralekha Chowdhury, then a young schoolgirl who studied at Patha Bhavan, and whose mother was the painter Chitranibha Chowdhury. We had in fact interviewed Supriyo Tagore, Indira Devi’s nephew and Chitralekha herself for our exhibition Time Upon Time, playing them the songs and recording their listening. Bake’s notes about his recordings are always scant, so throughout my work I have had to look at other sources for more information, such as his letters. I wondered if there was something in this report about his Bengal recordings from that trip.

Purnadas and his son Dibyendu Das, Kolkata, Sep, 2019

‘The outward journey by Clan Macintosh, from Liverpool to Calcutta was extremely comfortable and pleasant. A dock-strike in Liverpool threatened to cause considerable delay, but…’

I went skimming through the pages. He arrives in Calcutta via Colombo, goes on to Nepal, then goes to Delhi, then Benaras, comes properly to Calcutta. Eight months have passed since he had embarked on this journey. ‘Arriving in Calcutta on the 24th February we just escaped being stranded in the general–and complete–strike on that day. Zero hour was 6 a.m. and our train arrived at 5.30 a.m., which made it just possible to catch one of the last taxis running, to reach the boarding house before everything came to a standstill. My wife and myself, the driver and an assistant and 26 pieces of luggage (including my recording equipment) in one single not too large taxicab. The hartal had been organised as a protest to the proposed merger of Bihar and Bengal to one administrative unit (as it had been up to 1912 or thereabouts), and was only one of the manifestations of popular –or political–dissatisfaction with the decrees from Delhi. On the whole, things went without loss of life, except for a couple of poor shopkeepers, who thought that, as on previous occasions, the hartal would be over at 4 p.m. instead of at 6 p.m. as decreed and who were promptly stabbed to death.

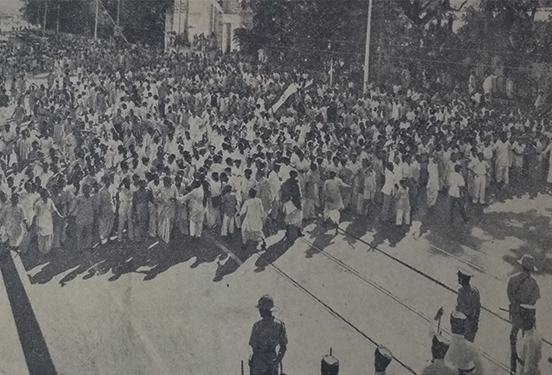

From local newspapers, photos of satyagrahis protesting the merger of Bihar and Bengal

‘As luck would have it, there was a festival of Bengali folk music shortly after we arrived and I was able to take several records of Vaishnava religious songs as sung by groups of wandering mendicants from West Bengal. Kindness and helpfulness from old and new friends were most enjoyable and made the days unforgettable. The same was the case during our visit to the Santiniketan after an interval of nearly 20 years. Also there I had the opportunity to make some interesting records of Oriya songs and folk music and Bengali songs, including the rendering of one of Tagore’s songs by his niece, aged 82–the acting Vice-Cancellor of Visvabharati University–a remarkable achievement on the part of the old lady.

‘On our return to Calcutta, I had hoped to acquaint myself with the stock of recordings anthropologists of the Indian Museum had made in the field, but an unexpected setback in health…’

I knew the song of Tagore’s niece of course, many know it; it seems that Indira Devi used to like to sing this song, ‘Katobaro bhebechhilo’, during this time (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=K9bb9dumEM4). But what is his Bengali folk music festival he is talking about? Where are the recordings he says he made there? I asked Janet and she in turn asked their Bake-in-Bengal researcher, Christian Poske. He brought out two audio files marked C52/NEP/67 and C52/NEP/68. C52 is the Bake Collection at the British Library’s Sound and Audiovidual Archives. NEP would mean his Nepal recordings. By now Bake is no longer making recordings with the phonograph, on wax cylinders (1931-34), nor on the Teficord sound recorder, which he had used in the second phase of his field recording trips, from 1938. He was using a reel-to-reel recorder now. Bengali folk music recorded in Calcutta marked Nepal, with no other detail except to say Vaishnava songs. It is not surprising that after years of browsing the catalogue, and listening to Bake’s recordings, I had never found these.

Janet offered to open the files for me on her computer, so that I could listen. These were far longer sessions than anything we have had from Bengal so far; a wax cylinder could record for only about three minutes. These two tracks were of about 16 minutes each. I sat down to listen. The moment the first track, C52/NEP/67 started to play, I knew I had struck gold. I also knew I had no way to take these recordings back with me, no way to take them to people who would know and identify the singers, so I would have to listen as closely as I could and then use those those sonic impressions to find my way.

Here is the note I typed on my computer:

29.2.1956 and 1.3.1956—banga sanskriti sammelan?

Calcutta

C52/NEP/67 16:34 track

Religious Vaisnava songs, sung by the mendicants

Jiban he nutan, nyay na jeno chore, dekho dekho mon—Sanatan?/Nabanidas? (Nilakantha) khamak ghungur kartal

Gurupade prembhakti holo na mon hobar kale—fakiri style—prasanna kumar

Gurupade prembhakti again

C52/NEP/68 15:11 track

Sonar manush eshechhe bhai dekhbi jodi aay/ogo tribhuban korechhe alo jhalok daey bidyuter gaay—same singer– dugi, ektara aar kortal (performing, can hear reverb) বয়স্ক

Kal shokale hori bole amay nitai probhu tene naey (female singer) –khanjani prochondo echo , khola space e gaan mone hoy. Dotara accompaniment—manju? / purno sister? Sounds like a young voice.

Purnodas surely—ore amar abodh mon /sarbada chetane thak re mon

Banka nodir gotik bojha bhar—adbhut ektana fakiri style

Ektara dugi, ghungur

I had to tell Janet after I finished listening, that this was no ordinary recording, but I refrained from saying anything more. I asked if they would upload the recordings along with their other Bake-in-Bengal tracks (https://sounds.bl.uk/World-and-traditional-music/Arnold-Adriaan-Bake-South-Asian-Music-Collection), they said they could not do that just now. I was excited and worried too. I felt like I was holding something very precious in my hands and I knew I would have too take extra care of it. Such knowledge is, in fact, very fragile; a momentary lapse and it can break.

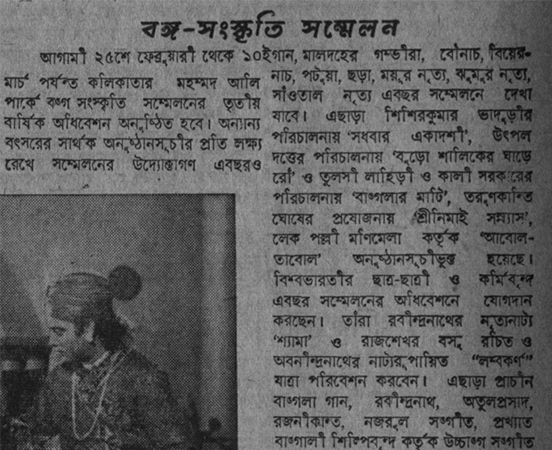

The following months, back in Kolkata, I had to think of ways by which I could establish the provenance of those two tracks. Where could I start working with a sound, which I did not have with me and which lay silent in the vaults of an archive many seas away? Dates, I thought. 29 February and 1 March 1956. What was the festival that Bake was talking about? Could it be the Banga Sanskriti Sammelan. A young friend, something of a bibliophile, Apurba Roy, and I tarted to search through old newspapers. 1956 was a leap year and indeed, the Banga Sankriti Sammelan had opened on 25 February that year. We found photos in the papers, the pandal at Muhammad Ali Park had caught fire the afternoon before the festival was to begin, but organisers promised to start at the same venue on the fixed date. The doyen of Bangla stage Sisir Kumar Bhaduri would open the festival. Historian Nihar Ranjan Roy would speak. The whose-who of Bengali literary and cultural world would descend on the pavilion, from classical to art song, theatre and folk performances too. Kalipada Pathak, Indubala, Angurbala, a troupe from Santiniketan, Nirmalendu Chowdhury, Sheikh Gomani Dewan… We searched programme announcements for names of the baul singers, and went through reviews to find something about who had performed. There was nothing. No name of any of the singers who I thought I had heard in the recordings at the British Library.

News of festival fire and review

So I decided to meet Purno Das Baul and ask him if he remembered performing at the festival in 1956; if his father was there and who else might have been with them. If Arnold Aadrian Bake had recorded Nabani Das Khepa Baul in 1956, then it was history. Nabani Das Khepa Baul (1890-1964), who shines in a galaxy made up of such stars as Rabindranath, Kshiti Mohan Sen, Shambhu Saha, Shantideb Ghosh, Mukul Dey, Deben Bhattacharya, Richard Lannoy…

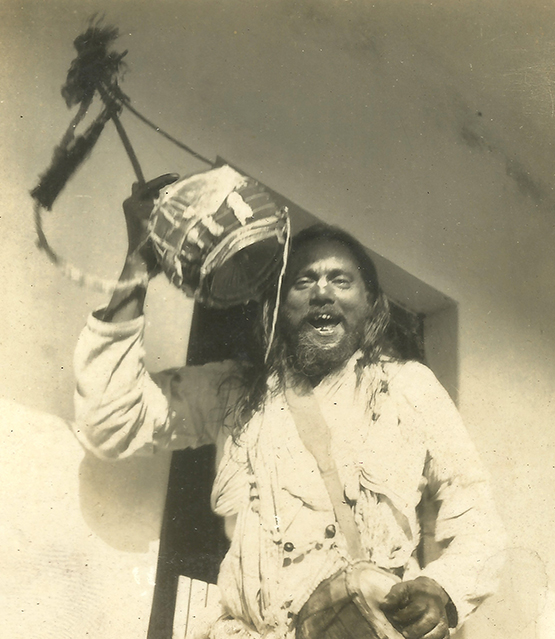

Richard Lannoy photo of Nabani

We know about the first and only recording of Nabani Das Baul and the first of Purno Das and Lakshman Das, made by Deben Bhattacharya, at the Banga Sankriti Sammelan of 1954. Debenbabu has talked and written about it. There are enough publications from that trip to stamp it with lac. After all, Debenbabu was the kind of recordist who made sure he carried his recordings out into the world. In one his last and final conversations with the actor and theatre director Aly Zaker in Dhaka in 2001, he had talked about that trip and about the festival, about how he had come with his photographer friend Richard Lannoy, how he had recorded Abbasuddin and Nabani Das Baul, how he had gone back with cans and cans of songs and tunes, enough to compile many albums. We have heard from Deben Bhattacharya’s wife, Jharna Bose Bhattacharya, stories about Deben and Richard’s trip to Nabani Das Baul’s home in Suri. All of this is known history now and the two songs of Nabani Das Baul, the only recordings of his voice so far heard, are available, even on the internet.

Listen to a Nabani Das song recorded by Deben Bhattacharya in 1954, Gour chander haspatale

The Purno Das and Lakshman Das recordings of Deben are another story. How they played a role in opening the doors to a whole wide world for the bauls. How they carried a sound to the West which also led to the making of a sound. That should be the subject of another session note.

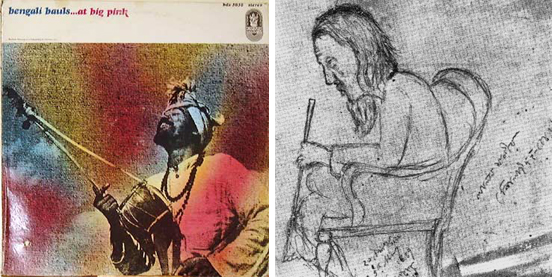

Cover of Bengali Bauls at Big Pink, released by Budda in 1968 (left). The image they used was Sambhu Saha’s portrait of Nabani Das Baul taken some time after 1937. This image is as iconic to baul matters as Jyotirindranath’s sketch of Lalon Fokir from 1889 (right).

I met Purno Das Baul and his son Dibyendu (Chhoton) in their home in Dhakuria, south Kolkata, on 7 May 2019 . The 86-year-old Purno Das remembered the Banga Sanskriti Sammelan, although he got some details of the fire mixed up. He insisted the venue had been shifted after the fire, which was not the case. Never mind that. As I read out from my notes, and told him what I had found out from the papers, he began to talk about his father’s songs, their musical family, his own musical journey, the fire in the tent during that year’s festival, and much more. This is how we have organised the recording from that day.

00:00 Chapter 1: Talking about the 1956 recording

15:40 Chapter 2: On Nabanidas Khepa

21:30 Chapter 3: More songs. First trip abroad, to Russia. Did not know anything about the value of archiving. Hence, so much has been lost.

25:56 Chapter 4: American trip in 1967, following Allen Ginsberg’s visit to their home and later of Sally [and Albert Grossman, of Woodstock fame]. Other singers in their group were Purna’s brother Luxman Das Baul, Ashok Fakir and Sudhananda Das.

27:46 Chapter 5: Family, lineage

32:51 Chapter 6: More on Nabanidas

33:34 Chapter 7: About Edward C. Dimock and Charles Capwell

34:15 Chapter 8: Voice of Purno Das’ mother Brajabala (Nabanidas’ wife)

40:16 Chapter 9: About photos, Sambhu Saha, Sai Baba

43:50 Chapter 10: The historical importance Purno Das Baul and his early recordings

We then decided that Purno Das would write a letter to the British Library and tell them about what he had heard from me and about how he was convinced the recordings were of his father and their own songs. And how they would like to have a copy of the recordings.

The rest does not need elaboration. The letter was taken, the plea heard, the recording repatriated by the British Library. A happy ending for all.

What we have here are a set of recordings from a session when we listened together to the recordings the British Library had sent to Purno Das Baul. We cannot play here the archival recordings as we do not have the permission to do so. Here is a recording of our listening to the recording. Such as the photos of photos we take, and bring back with us, this is a recording of a recording of a recording–many times removed from the source, but a source in itself.

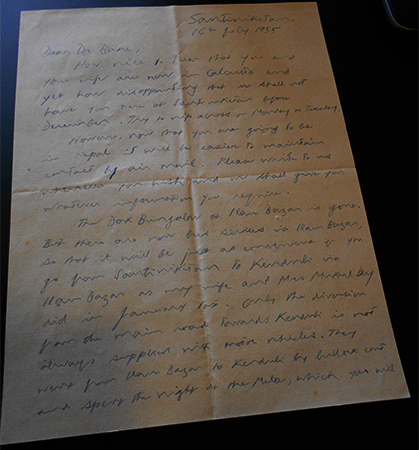

Strange streams meet in this story. The Santiniketan world of which Nabani Das Baul was a part was also a world which formed Arnold Bake. He went there as a 26-year-old young researcher in 1925, and his love of Indian music, songs of Rabindranath, folk music, the bauls, kirtan–so much came out of his years of association with the place and deep friendships he forged there. Not only because of Santiniketan, but surely that time in his life played a huge role in the choices he made. Which is why, before coming on this 1955-56 trip, he was writing to his old friend Annada Sankar Ray and making plans about what they might do, how they can listen to baul songs, how they might go to Kenduli. And Roy suggests that he consult Mrs Mukul Dey about this, as they have recently gone to the Kenduli mela. Interestingly, there are among the private papers of Mukul and Bina Dey (http://www.chitralekha.org/) evidence of the fact that Bina [Mrs Mukul] Dey would visit Nabani Das’ akhra. She wrote down directions to the place as well as words of songs in her notebook. This same Bina was also a friend of Mrs Bake’s, for they had met in their youth on the grounds of Santiniketan. Here s a photo of a photo of a photo–something from the library of the University of Leiden, where Bake was a student and where many of his papers are housed.

Photo from the library of Leiden University

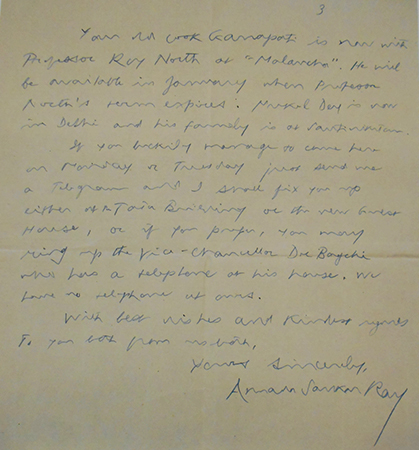

Annada Sankar Ray letter

The fact of Arnold Bake’s non-recognition of Nabani Das Baul, or at least the fact that Nabani remained unmentioned in Bake’s notes, troubles the mind. We speculate on answers. What is an archive? What do we keep in an archive? What do we fail to keep? What happens to the unrecorded part of the story? Is it lost forever, or does it remain in some other form, as another kind of trace?

At The Travelling Archive, we are often faced with this question. We fail to keep records too. We fill in for the gaps left by people before us, someone else will fill is our own gaps. That is how life flows and knowledge grows. What is wonderful is that we have two new songs of Nabani Das Baul, a song of Sudhananda Das Baul (who came from a tradition of kobigan singing in East Bengal and hence had such a distinctive style), a song of the gentle Radharani Dasi, Purno’s sister who loved him so much that she refused to record for HMV when her brother was not offered a contract, the brilliant Purno Das Baul in his late teens, and his brother-in-law, Gopal Das, who was a yogi and travelled about, singing songs. ‘Perhaps Radharani would accompany him if she did not have to care for her infant nephew,’ wrote Charles Capwell in his book Sailing on the Sea of Love. ‘She and Gopal have no children of their own because, as Laksman explains, they are yogis; that is, they are adept at baul sadhona… Radharani likes to sing and does so well; nevertheless she does not get as much opportunity to sing as she would like because most of the attention is given to men.’ Perhaps Radharani longed for her own child too, like she longed to sing? How to know? Where do we find the record of such things?

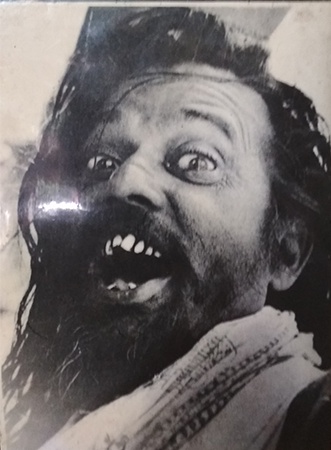

We will end this session note with two beautiful photos by a woman artist from Santiniketan, Kiron Barua, who was born in 1924 and studied at Kala Bhavan, Santiniketan. She captured the madness of Nabani Das Baul, the khepa baul, with her Rolleicord camera, some time in the 1950s. This is how we can assume Nabani Das Baul to have looked on stage when Bake was watching her perform.

Written by Moushumi Bhowmik and page designed by Sukanta Majumdar, Aug, 2020

Related link:

https://www.anandabazar.com/supplementary/rabibashoriyo/story-of-nabani-das-baul-father-of-purna-das-baul-article-by-moushumi-bhowmik-1.1193096 (accessed in Aug, 2020)

- Saptiguri, North Bengal. 27 November 2003. Nirmala Roy

- Bolpur, Birbhum. 25 November 2003. Nimai Chand Baul

- Surma News Office, Quaker Street, East London. 27 February 2007. Ahmed Moyez

- Ambikapur, Faridpur, Bangladesh. 29 April 2006. Hajera Bibi

- Sylhet, Bangladesh. 22 April 2006. Chandrabati Roy Barman and Sushoma Das

- Sylhet, Bangladesh. 21 April 2006. Arkum Shah Mazar

- Sylhet, Bangladesh. 20-21 April 2006. Ruhi Thakur and others

- Jahajpur, Purulia. 27 February 2006. Naren Hansda and others

- Faridpur, Bangladesh. 24 January 2006. Binoy Nath

- Uttar Shobharampur, Faridpur, Bangladesh. 22 January 2006. Ibrahim Boyati

- Baotipara, Faridpur, Bangladesh. 21 January 2006. Kusumbala Mondal and others

- Kumar Nodi, Faridpur, Bangladesh. 21 January 2006. Idris Majhi and Sadek Ali

- Debicharan, Rangpur, Bangladesh 18 January 2006 Anurupa Roy & Mini Roy, Shopon Das

- Mahiganj, Rangpur, Bangladesh. 17 January 2006. Biswanath Mahanta & Digen Roy

- Chitarpur, Kotshila, Purulia. 28 November 2005. Musurabala

- Krishnai, Goalpara, Assam. 30 August 2005. Rahima Kolita

- Chandrapur,Cachar. 28 August 2005. Janmashtami

- Silchar, 25 August 2005, Barindra Das

- Kenduli,Birbhum. 14 January 2005. Fulmala Dasi

- Kenduli, Birbhum. 13 January 2005. Ashalata Mandal

- Shaspur, Birbhum. 8 January 2005. Golam Shah and sons Salam and Jamir

- Bhaddi, Purulia. 6 January 2005. Amulya Kumar, Hari Kumar

- Srimangal, Sylhet. 27 December 2004. Tea garden singers

- Sylhet, Bangladesh. 26 December 2004. Abdul Hamid

- Dhaka, Bangladesh. 24 December 2004. Ali Akbar

- Dhaka, Bangladesh. 23 December 2004. Monjila

- Changrabandha, Coochbehar. 16 December 2004. Abhay Roy

- Santiniketan, Birbhum 27 Nov 2004 Debdas Baul, Nandarani

- Tarapith, Birbhum. 14 October 2004. Kanai Das Baul

Mam ,thanks for sharing this with us not only for archival value also add values to morder society ..thanks again