Surma News Office, Quaker Street, East London. 27 February 2007. Ahmed Moyez

aparadhi hoilam ami e kon bichare

This was my second meeting with Ahmed Moyez, Sukanta’s frst. I had met him in August 2006 in the office of Betar Bangla–a Bengali/Bangadeshi, more specifically Sylheti, radio station in Bethnal Green. Ruhul Amin, Sylheti filmmaker in London, had taken me there and many other people had also come—mainly students and intellectuals from the Sylheti community. Some knew about my research, some my own music, some were just curious to find out what was going on. For the diaspora, such visits are very important; they help to establish links with the left-home and also to forge new identities in the new home. Music becomes the vehicle for this two-way homeward journey.

Ruhul knew I was looking for songs and stories related to the theme of migration, memory and music and he was taking me around to meet people. About Moyez he had said that this man comes from a family of pirs or the spiritual poet-healers of the Sufi tradition, adding that he is immersed in music.

Ahmed Moyez made a strong impression on me on the first day, but there were too many people around. I hoped to go back to him, with Sukanta. Our recordings from that session and later ones are kept at the British Library (http://sami.bl.uk) and now when I listen to them, I see the story of Ahmed Moyez slowly taking shape. Over the years every time we have met, Moyez has told the same stories and added some new ones; same with the songs. Layers of narrative are added, one over another.

Ahmed Moyez

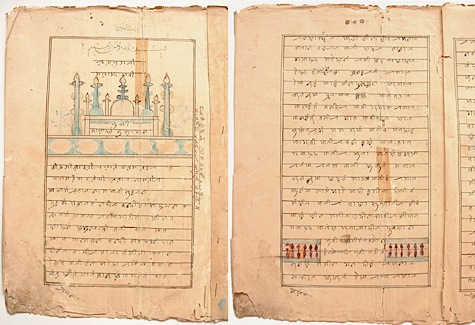

Moyez’s home was in Syedpur, Sylhet, where his poet-philosopher and spiritual healer grandfather, his dada, Pir Mojiruddin, once lived. He knows his grandfather’s songs, talks about his book Prem Ratan, shows some scanned pages from the manuscript. Here in this session, Moyez is singing one of Pir Mojir’s texts. He beats on the empty popcorn tub as if it were his small hand drum or dubki/dofki, and dances to the rhythm of the song, which is about submission to the Creator and about the mystery of creation. প্রাণবন্ধুয়া রে, অপরাধী হইলাম আমি এ কোন বিচারে?

There are fascinating stories about his village life. Moyez talks about how his father healed madmen and women; about how his grandmother would light the lamp every Thursday and offer shinni to the spirits; about how there were spiritual and artistic ways of taking shiddhi or ganja—‘Not quite like how our city intellectuals smoke up for fashion,’ he says. He talks about music being in the air all the time. He studied in a madrassa or Islamic religious school in Sylhet; he says it was there he became aware of the debate of the siddhiwala vs. the shariatwala—those who were free-flowing spiritual teachers, against those who lived by the Book. Which side he is on is hard to say. I suppose back in the days of Pir Mojir it was easier to be either or. Can one be both at the same time? In 2009 after a music session or sadhu-shongo with some Kushtia bauls on Dhaka Art College grounds, there was this young artist, one of the organisers of the evening’s music, narrating to us how terrible he felt to be in India, how Hindu we were and how oppressive. There surely were reasons for him to feel this way. But there was also reason for us to start feeling cornered. We were no longer partakers of the evening’s music, which tells us to go beyond caste, creed and nation, jaat and dharma.

Moyez came to the UK as a young adult, perhaps through marriage—I have never asked him why. His wife is a second, maybe third generation British Sylheti. They have five children. So life is quite complicated now. Moyez’s entire family, even his mother, have left Syedpur and live in London. This route from ‘Sylhet to Bilet’ is an old one (‘The Bengali word ‘bilet ‘ is a derivative of the Persian word ‘vilayet’ meaning foreign land. In this context it refers to England). There are many reasons for people to make these journeys. Bilet holds the promise of a better life, I suppose. Whether Moyez’s life now is ‘better’ than what it could have been in Syedpur. I cannot tell. Maybe he cannot tell either.

Pir Mojiruddin’s manuscript

Better and worse are such relative terms. But with time the place of arrival also becomes home, for better or for worse. Ahmed Moyez lives by the fish market in Shadwell. His family is scattered all over East London, there are friends and relatives in Birmingham; also whole neighbourhoods of Syedpurians in the North Sea coast town of Hartlepool. In 2006 Moyez had told me that in this little town there were immigrant areas where you could hear music as in a village congregation; sounds of drumming and singing typical of the ‘aashor’. In fact this is the story which I found most fascinating right from the start and some day, I want to go on its trail. Perhaps this merely comes out of Moyez’s imagination and I will go and find that it is not like that at all. Instead, Sayeedi’s Islamic waz or religious oration in Bangla will be playing in some corner shop.

At the time of this recording in 2007 Moyez was a part-time journalist of Surma News, an East London newspaper. He lived an almost invisible life then, lost in the crowd. His English was limited, his map of London had only a few familiar streets, beyond which he seemed frightened to travel. But on the streets he knew, he moved about in the relative comfort of his own language, culture and identity.

This East London Bengali/Bangladeshi world is a world within worlds. In many ways it is informed and formed by the country the immigrants come from. It also influences that world, even shapes it, through the power of the GBP and owing also to the fact that it is a part of Bangladesh placed in the centre of the world. Many scholars have researched and written about this two-way impact. Now in 2014, when I am writing this note, Moyez has become editor of Surma News and he also runs a web-design company, Harappa. Has this so-called advancement given Moyez more power in his community? Does this give him a more secure place? Or does this success come for a price? Moyez had organised a presentation for me in Brick Lane in November 2013, where I was to talk about The Travelling Archive. While he was passing the buck to someone to introduce me, I insisted that he does it, as he is familiar with my work. He was hesitant. I don’t know why. I sang a few lines of a song I had learned from one of his recordings; a composition of his grandfather, and then the ice broke. Moyez joined in, like someone who can momentarily forget every other obligation and inhibition, for the sake of the song.

মৃদঙ্গে উঠিছে ধ্বনি, শুনি তার পদধ্বনি রে

We have quoted this song many times in our work. In many ways the song has become independent of Moyez for us. For it is a song about dhwoni or Sound and Listening.

A sound rises from the mirdanga drum.

I hear its footsteps,

It stirs my heart,

I feel in me that rumble and roll.

Why, O why did I hear its call?

Written in May 2014.

Related links:

Bilet–http://books.google.co.in/books/about/Travels_to_Europe.html?id=1jkaZEUm3nEC&redir_esc=y

Scholars:

Katy Gardner http://www.lse.ac.uk/anthropology/people/gardner.aspx

Delwar Hussain

http://www.opendemocracy.net/author/delwar-hussain

- Saptiguri, North Bengal. 27 November 2003. Nirmala Roy

- Bolpur, Birbhum. 25 November 2003. Nimai Chand Baul

- Kolkata. 4 September 2019. Purnadas on Nabani Das Baul

- Ambikapur, Faridpur, Bangladesh. 29 April 2006. Hajera Bibi

- Sylhet, Bangladesh. 22 April 2006. Chandrabati Roy Barman and Sushoma Das

- Sylhet, Bangladesh. 21 April 2006. Arkum Shah Mazar

- Sylhet, Bangladesh. 20-21 April 2006. Ruhi Thakur and others

- Jahajpur, Purulia. 27 February 2006. Naren Hansda and others

- Faridpur, Bangladesh. 24 January 2006. Binoy Nath

- Uttar Shobharampur, Faridpur, Bangladesh. 22 January 2006. Ibrahim Boyati

- Baotipara, Faridpur, Bangladesh. 21 January 2006. Kusumbala Mondal and others

- Kumar Nodi, Faridpur, Bangladesh. 21 January 2006. Idris Majhi and Sadek Ali

- Debicharan, Rangpur, Bangladesh 18 January 2006 Anurupa Roy & Mini Roy, Shopon Das

- Mahiganj, Rangpur, Bangladesh. 17 January 2006. Biswanath Mahanta & Digen Roy

- Chitarpur, Kotshila, Purulia. 28 November 2005. Musurabala

- Krishnai, Goalpara, Assam. 30 August 2005. Rahima Kolita

- Chandrapur,Cachar. 28 August 2005. Janmashtami

- Silchar, 25 August 2005, Barindra Das

- Kenduli,Birbhum. 14 January 2005. Fulmala Dasi

- Kenduli, Birbhum. 13 January 2005. Ashalata Mandal

- Shaspur, Birbhum. 8 January 2005. Golam Shah and sons Salam and Jamir

- Bhaddi, Purulia. 6 January 2005. Amulya Kumar, Hari Kumar

- Srimangal, Sylhet. 27 December 2004. Tea garden singers

- Sylhet, Bangladesh. 26 December 2004. Abdul Hamid

- Dhaka, Bangladesh. 24 December 2004. Ali Akbar

- Dhaka, Bangladesh. 23 December 2004. Monjila

- Changrabandha, Coochbehar. 16 December 2004. Abhay Roy

- Santiniketan, Birbhum 27 Nov 2004 Debdas Baul, Nandarani

- Tarapith, Birbhum. 14 October 2004. Kanai Das Baul