Chitralekha Choudhury and the Story of a Disappeared Fresco

It was in 2015, while researching for The Travelling Archive in East London exhibition that I came across two recordings of Arnold Bake from 1956 which were from Bengal—there were two more recordings from that trip, which I did not notice till 2018. To those I have dedicated another sub-chapter.

The artist’s name for item number C52/NEP/70 C1 was Chitra Chaudhury. According to the accompanying archival note, she recorded a Tagore song for Arnold Bake in Santiniketan on 7 March 1956. C52/NEP/71 C1 was marked as a Tagore song sung by Indira Devi Chaudhurani, recorded on 10 March 1956. The place of recording for Indira Debi was given as Nepal, but that was obviously an error; I assumed this would also be Santiniketan, because I knew that Bake was visiting old friends in Calcutta and Santiniketan at the time.

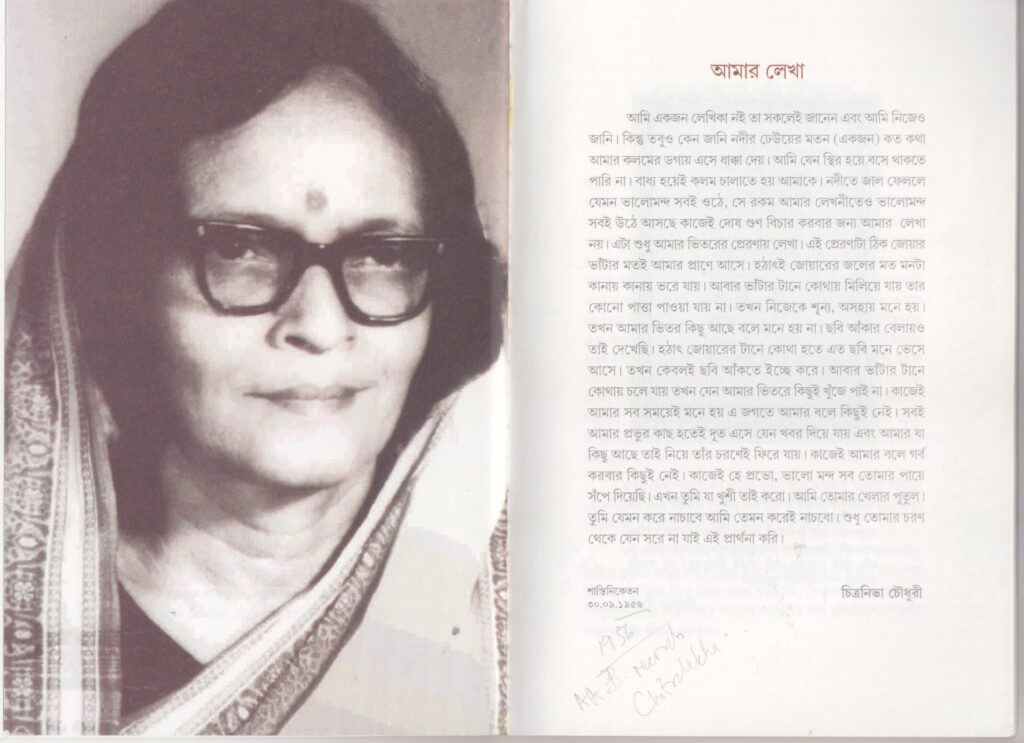

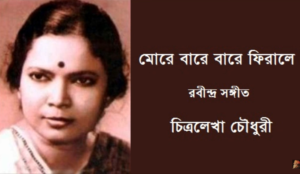

Chitralekha Chaudhury in her home in Sinthi, Kolkata on 16 November 2015.

As with many of the other Bake recordings, it was the archival note which came to me before the sound; hence, speculation began from the text. Could Chitra Chaudhury be the renowned Tagore singer Chitralekha Chaudhury is the first thought which crossed my mind. When I listened to the recording, I felt I had probably guessed right. In the recording, the singer is young, so I had to make some more inquiries before I could be certain. After the exhibition in London in June-July 2015, I returned to Kolkata and sought out Chitralekha Chaudhury. She was my old friend, also a singer, Nabanita Chattopadhyay alias Tuku’s teacher, so I asked her to find out if her guru remembered ever being recorded by Arnold Bake. Tuku said Chitralekhadi was keen to meet me and so sound recordist Sukanta Majumdar and I went to her home on 16 November 2015. The recordings of that evening in Chitralekha Chaudhury’s home were all made by Sukanta, the photos were taken by either of us. Chitralekha’s daughter Patralekha Reena was also present and we all listened together to the 1956 recordings of Arnold Bake and other recordings too. The recordings were keys to long-unopened vaults of memory. Chitralekha was listening to herself and remembering the day of the recording, her painter mother, Chitranibha, life in Santiniketan, old teachers and so much more. Those days people mostly called her Chitra; in 1956 she was a student of the secondary school of Visva Bharati, Patha Bhavan. Her mother, the painter Chitranibha Chaudhury, was among the early women graduates of Kala Bhavan, who also taught there later. ‘She was the first lady professor of Kala Bhavan,’ her daughter said with great pride.

Chitralekha Chaudhury listens to her song, ‘Amala dhabala paale legechhe’, and she begins by talking about how this was the song she would often sing in those days. Born in 1940, Chitralekha was fifteen going on sixteen at the time of the recording. She talks about early music lessons in Santiniketan from master teachers and how her mother made every effort to arrange for the best music education for her daughter. She sings a few lines of the song she had sung as a child for Allauddin Khan, ‘Jago jago’, when the master came as a visiting professor to Visva Bharati. She recalls the transcendental quality of his music and the depth of his sadhana and his total humility as a person. She especially mentions a performance one autumn evening where the master sat and played for over two hours, his white robe turning green as seasonal flies landed on him and bit him to their fill. The artiste was totally impervious to such mundane matters; after his performance the lord stood up and shook the flies away. Chitralekha also remembers the singer of the Bishnupur gharana, Gopeshwar Bandopadhyay’s visit and how he gave her individual lessons because she was too small to learn in a group and how he slowly prepared her to sing with him during performances. She recalls her ‘guru bon’, fellow student of Gopeshwar Bandopadhyay, the famous Hindustani classical singer Malavika Roy (later Kanan), already on her path to fame.

Allauddin Khan in Santiniketan, with the painter Nandalal Bose on his right and Tagore singer Sushil Kumar Bhanja on his left. Scanned from Robibar, the Sunday magazine of Sanbad Protidin, 2 March 2015 (Kolkata: Protidin Prakashani Limited, 2015), p.24.

Chitralekha tells us the story of how her mother was married, how Chitranibha’s in-laws recognised her potential as an artist, and how they believed that in the struggle against British rule, women would play a vital role, so they had to be prepared for it. That is how she came to Tagore’s school in Santiniketan to study at Kala Bhavan with Nandalal Bose and others. She also learned to sing from Dinendranath and Rabindranath himself.

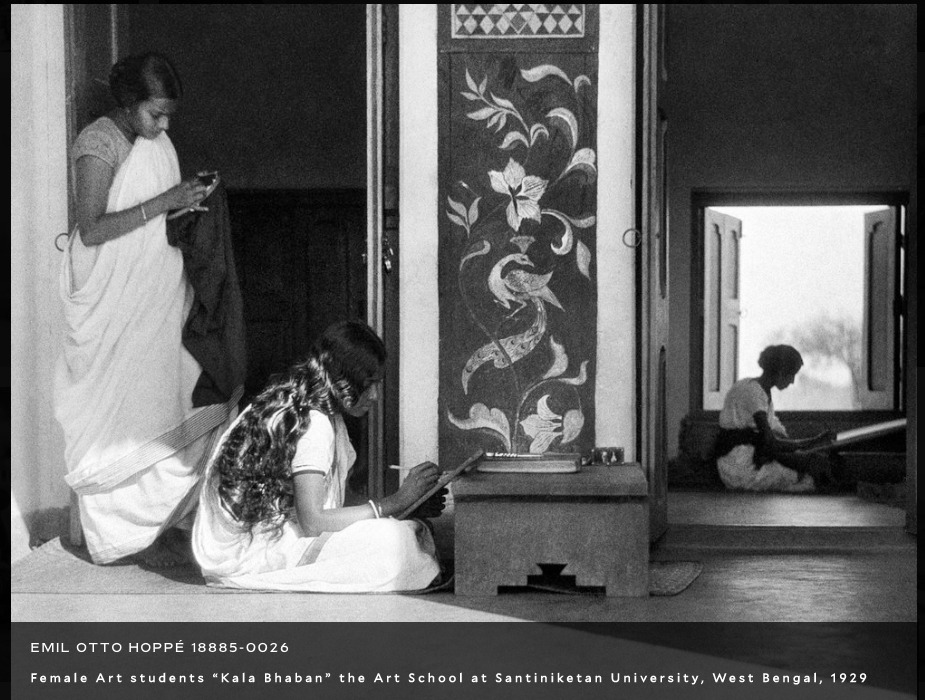

This photograph is from E. O. Hoppe’s book, Santiniketan; it was on the cover of the book. The photo was taken in 1929 and it struck me that one of the unidentified women could be Chitranibha Chaudhury. As we hear in this telephonic conversation on 12 February 2022, Chitralekha, has identified the woman with flowing hair and shankhaa (conch shell bangles), sitting on the floor, as her mother. Image source: Internet.

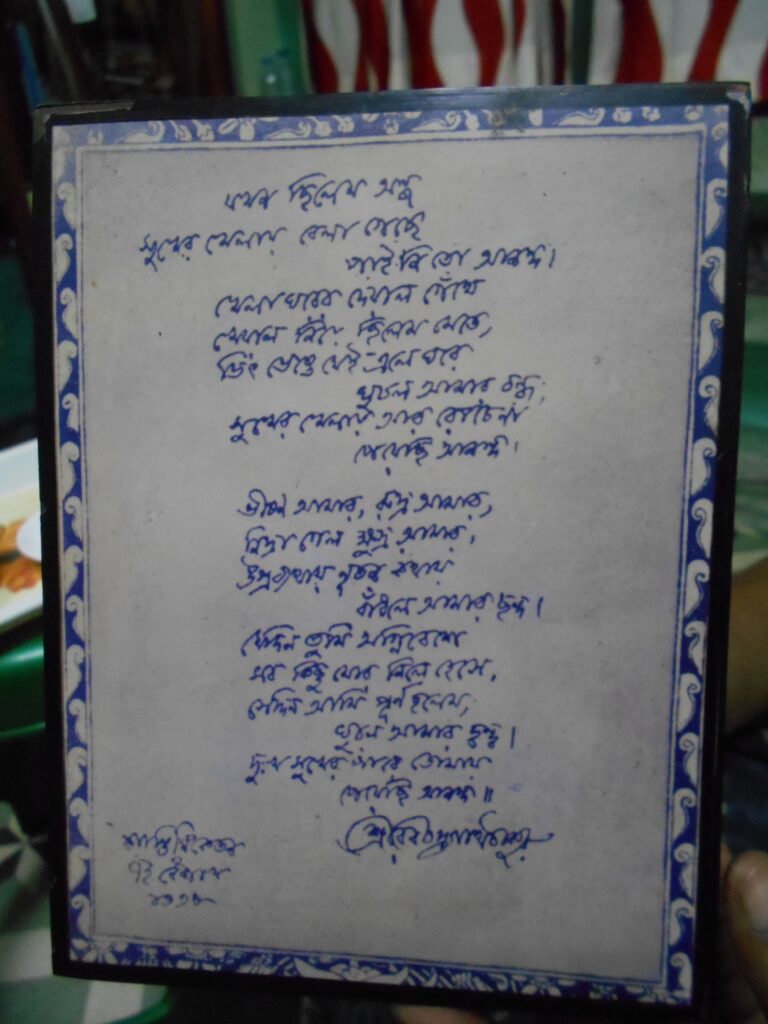

Chitralekha continues to tell her mother’s story. How her mother had to regularly report to Rabindranath about her progress. She would go and show him her work. One day she took a design of a rectangular frame, with nothing inside. Rabindranath said, why this empty space? Maybe you should write a poem. She said, but I can’t write poems. He said, then leave it on my desk. The next day she went and found that Rabindranath had written a beautiful song about blindness and the awakening of sight to fit her frame.

Chitralekha talks about their family estate in Lamchor village in Noakhali, now in Bangladesh. This was a prominent zamindar or landowning family. On her father’s side of the family they were all scientists and educators, they had set up schools in the village, their house was like a boarding for students who were also trained in rifle shooting, because they would have to fight the British. Her father, Niranjan Chaudhury, was a member of the Anushilan Samiti. She said, later that training came to use during the communal riots of 1946. All around them there was killing, arson and looting, but their lives and property were saved. Chitralekha tells us how her mother went home to her in-laws after five years in Santiniketan and the house seemed like a hostel to her. Chitralekha also tells us how her mother’s original name was Nibhanoni but Rabindranath changed it to Chitranibha, because she was such a good painter. That is the name she came to be known by later.

Page from Chitranibha Chaudhury: Smritikatha (Kolkata: Rajya Charukala Parshad, 2015)

Chitralekha briefly mentions the fresco that her mother had painted in her uncle’s house in Dhaka. Chitranibha’s husband had studied mathematics and his elder brother, Chitralekha’s jethamoshai or uncle, Professor J. C. Chaudhury, was head of department of chemistry of Dhaka University. The fresco in question was painted in his house. This fresco and its disappearance have slowly come to hold metaphorical meanings for me in my research, symbolising history buried under history, but we will come to that later. For now, Chitralekha goes on to talk about the riots in Noakhali, about how Gandhi had stayed in their house after the communal riots of 1946. Her father, Niranjan Chaudhury’s room was where Gandhi had stayed, she says, her uncle’s room (I believe she meant her uncle Manoranjan Chaudhury, who was a friend of Gandhi’s) became his private secretary’s office (Chitralekha could not recall the name, but of course she meant Nirmal Kumar Bose). She says, the memory of the riots was too bloody, which is why she has never been able to go to Bangladesh.

As I was listening back to these recordings in 2021, I realised that there were some gaps in my understanding of the Lamchor Chaudhury household, of Chitralekha’s father Niranjan Chaudhury’s circumstances and so on. So I called Chitralekhadi and we spoke on the phone about things. It is interesting to think how memory works. She repeated some of the things she had said in 2016, such as her mother proposing to her father that maybe they could think about exchanging their Noakhali house with her friend Firoza Bari’s in Park Circus, Calcutta. Her father had apparently said, are you crazy? This is all temporary, Hindus and Muslims will come back together again. And then she told me again on the phone how her father really did not want to come and how Gandhi had said to them that you must not leave and how he finally said. ‘I can part with one of my limbs but I cannot part with my party.’ Whether or not this is historically accurate is not for me to say, but this is how Chitralekha knows and tells and retells her own history, the history of her family as well as the history of a nation.

Conversation with Chitralekha Chaudhury on the phone, 31 May and 1 June 2021.

This is again from 16 November 2015. Chitralekha Chaudhury tells us the story of how this elaborate fresco that her mother had painted in the house of her brother-in-law, Professor J. C. Chaudhury, in the late 1930s after she had graduated from Santiniketan, was finally ‘lost’.

When Partition was imminent, Professor Chaudhury exchanged his property in Dhaka with a family in Calcutta. Apparently, when leaving the house and the country, he had told the new occupants to look after Chitranibha’s fresco. ‘Murals are not just paintings or relief on the wall; they generate in the building or its surroundings a new kind of vitality. Their role, therefore, is organic, not ornamental,’ K. G. Subramanyan had said. There are many styles of mural painting; fresco is one of the toughest, as artist and scholar Professor Nisar Hossain, who has written on Chitranibha’s lost fresco, was explaining to me. The fresco of Chitranibha in Dhaka became shrouded in mystery after Partition—people talked about it; Chitralekha and her mother heard stories about it from visitors from Dhaka. Meanwhile, the house changed hands again. Parallel to these happenings, Nisar, who teaches at Charukala, the art school of Dhaka University, had set out on his own journey to find this bhittichtro or fresco, of which he had heard so much. The house was located on 12 Topkhana Road, Segunbagicha, Dhaka. He reached it through a circuitous route and the journey was not easy. The room with the fresco was found—it used to be a large hall, according to earlier descriptions, but now it had been partitioned and it was the office of a company which sold water pumps. The room with the painted wall was now a storage piled with boxes to the ceiling. The wall with the painting was found, but problem was that it had been whitewashed.

Caption: While the walls of the house with the mural have now been whitewashed, these faded photographs of the mural which lie behind the white wall have been shared with me by Nisar Hossain. Nisar had these from Abdul Hamid of Bitopi advertising agency, who were working once on a calendar project on Dhaka’s murals (I do not know if the calendar was printed. One panel bears the signature of Chitranibha and the date is 7 Chaitra 1349 (BS), which would be March 1943. However, Chitralekha insists the fresco was painted before she was born. Hence the assumption is that Chitranibha had signed the mural during a later visit to Dhaka.

There were traces of Chitranibha’s village scenes behind the coating of lime and blue; there were pencil-marks still visible on the wall. On 20 February 2016, I went with Nisar to the house where the largest fresco panel of Bengal had been painted around 1939, prior to Visva Bharati’s Hindi Bhavan mural, painted by Benodebehari Mukhopadhyay in 1946-47. Nisar showed me signs of the fresco, which his expert eyes could see. Everything hinted at a history now impossible to see, but a history that lies under the surface of the obvious and the visible.

What used to be Professor J. C. Chaudhury’s house. 2016. Photos: Jan-Sijmen Zwarts

Visiting 12 Topkhana Road, Segunbagicha, Dhaka with Nisar Hossain and others on 20 February 2016. Jan-Sijmen Zwarts, a young Dutch scholar, who was staying with me at the time and helping me read Arnold Bake’s letters, had also come to Bangladesh. I made this recording on my Zoom H4N recorder.

On 16 November 2015, Chitralekha Chaudhury had talked about her first album, a 78 rpm record. The Tagore songs on the two sides of the two sides of the album were ‘More bare bare phirale’ and ‘Ei je kalo matir basha’. She narrated her father’s initial objection, her mother’s encouragement, and finally how she was recording record after record and her songs were playing all the time on the radio, while she was studying for her Masters and then she started to teach in a college and went on to do her PhD and so on.

Chitralekha Chaudhury tells a funny story about how she ended up going for military training and how she carried her harmonium to the camp and so on.

Finally, we come to Arnold Bake’s recordings, we listen again, I explain to Reena that I cannot give her a copy of her mother’s songs but she records while we play. Interestingly, after I sent Chitralekha Chaudhury’s postal address to the British Library after our meeting in November 2015, they sent her a copy of her 1956 recording with a standard letter explaining what was being given to her and how she must keep it and how she must not make further copies. Rules are rules, but we have to also find our own ways of dealing with these systems. Reena, also a singer, wanted to keep a copy of Indira Devi’s song too, and how else could she do it other than by recording on her tablet while I played the song? Chitralekha talks about Bibidi (Indira Devi) and about learning songs from her. I ask her about some of the other people Bake had recorded in Santiniketan. She tells me what she remember. Laksmisvar Sinha used to talk about the land of endless sunrise and endless sunset. Gurudayal Malik was very sweet and kind and when my little brother touched his feet and did pranam to him, he touched my brother’s feet in return and said, god lives in the heart of the children. I also play them Arnold Bake’s own recordings of Tagore’s songs and ask her, if he is singing in Dinendranath’s style? He is and he is not, she says. He is also a Western trained singer, she clarifies..

Chitralekha is married, she has gone for post-doctoral research to Laval University in Quebec and thinks she should learn some Western classical music. She goes for voice training but realises that is not for her. So, she takes to learning the piano. Then her teacher, Marie, asks her one day about Tagore and asks her to sing one of his songs. Chitralekha plays the piano and closes her eyes and sings ‘Chokher jole laglo joar’. There is total silence. When she opens her eyes, Chitralekha sees tears streaming down her teacher’s cheeks. Here was someone who had never been anywhere outside her own world of sound and listening, yet here she was so deeply moved by a song.

‘Time Upon time: Arnold Bake in Bengal’ is an exhibition we had in 2016 in Nandan gallery, Kala Bhavan, Santiniketan. Our main guests that evening were Chitralekha Chaudhury, who had been recorded by Bake in 1956 and Nirmalendu Mitra Thakur, whose father and grandfather and uncles and cousins had been recorded in Mainadal, Birbhum in 1933.