Footsteps of Sound 2013

This is an audio-video installation artwork we created as The Travelling Archive, for an exhibition on early sound recording in India, ‘La Presencia del Sonido’ (The Presence of Sound) held at Foundacion Botin, Santander, Spain in August-September 2013. The exhibition was curated by Nida Ghouse and Nuria Querol.

The Travelling Archive wrote a long essay for the catalogue as well as an introduction to their artwork.

Here is the introduction to Footsteps of Sound.

A sound rises from the mirdanga drum.

I hear its footsteps,

It stirs my heart,

I feel in me that rumble and roll.

Why, O why did I hear its call?

–Mojiruddin, early twentieth century mystic poet and pir of Syedpur, Sylhet.

What did Arnold Bake hear in that January of 1932 when he was recording and filming in Kenduli, the ancient annual fair dedicated to the 13th century poet Jaydev, on the bank of the river Ajoy, in Birbhum, Bengal? Standing in the middle of the chaos of Kenduli today, squashed from all sides by crowds, with noises rising from every corner of this space, where to look for the sound and the silence that Bake could have heard? Listen to his cylinders from that recording session? What we hear is not what he heard. It cannot be.

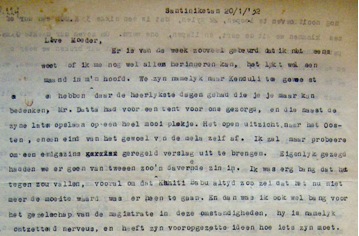

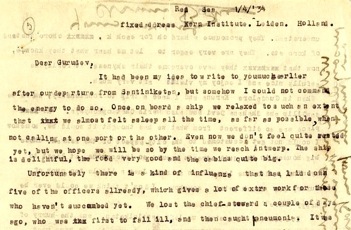

Letter Home. Bake to his mother from Santiniketan. 20 January 1932. Source: Kern Institute holdings at the Special Collection section of Leiden University Library.

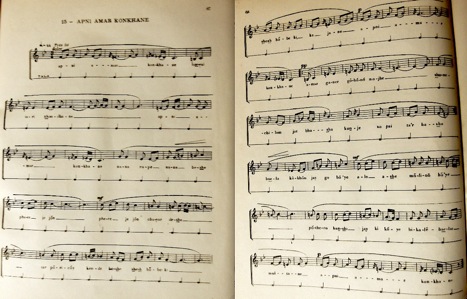

They were recording in Kenduli between 14 and 16 January 1932. Kenduli Mela, where the bauls come with their songs. ‘Song to them is a necessity, for it expresses the yearning of their soul,’ Bake wrote in his book with Phillip Sterne, Twenty-Six Songs of Rabindranath Tagore . On 31 January 1930 he had recorded an album with Pathe under the supervision of Hubert Pernot. ‘Chansons de Rabindranath Tagore’. One of the songs in it is Apni Amar Konkhane.

From Twenty-Six Songs of Rabindranath Tagore. Paris: Librarie Orientaliste Paul Guenther, 1935, pp. 67-68.

Bake’s note in this book about the song goes like this: A song entirely in the style of Baul songs of Bengal. The theme as well. . . it has direct appeal and not the metaphysical associations which a theme like that would have for a Western mind. The accent, often falling on the last note of a melodic figure, gives the song that urging and questioning character, wonderfully expressive of the essence of the bauls.

Do we hear in Bake’s recording something of what he had heard in this song? And, retracing these footsteps of sound, can we hear in it something of what Tagore might have heard in the songs of the bauls?

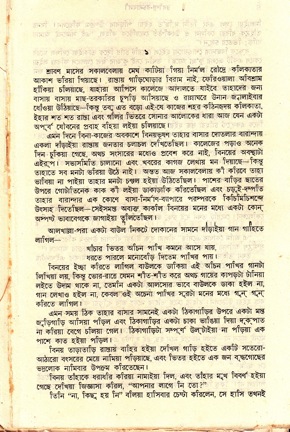

Image: Rabindra Rachanabali (Complete Works of Tagore), Vol. 9. Calcutta: West Bengal Government, 1961, p.3.

Tagore’s novel Gora (1910) begins with a scene where a baul is singing in a street of Calcutta. Binoy, a nineteenth century young Bengali intellectual, hears him from his balcony. It is a song about the mystery of the comings and goings of the ‘unknown bird’ into the cage of life. He wants to call the baul and write down the words of the song, but he is also feeling sluggish.

‘The first Baül song, which I chanced to hear with any attention, profoundly stirred my mind. Its words are so simple that it makes me hesitate to render them in a foreign tongue, and set them forward for critical observation. Besides, the best part of a song is missed when the tune is absent; for thereby its movement and its colour are lost, and it becomes like a butterfly whose wings have been plucked. The first line may be translated thus: “Where shall I meet him, the Man of my Heart?”’ From lecture ‘An Indian Folk Religion’, by Rabindranath Tagore, compiled in Creative Unity. London: Macmillan and Co. Limited. 1922.

After their second India trip, the Arnold and Cornelia Bake were returning home.

Sailing on the Red Sea. Bake’s letter to Tagore. 1 April 1934. Source: Rabindra Bhavan, Visva Bharati, Santiniketan.

‘All the sailors and stokers come from East Bengal and as the captain allows me to go wherever I like, I have heard quite a number of songs from their districts, mostly Sylhet and Noakhali. Some songs are really very attractive. Their dialect is not easy to understand. They pronounce a hard ch for each k, choro instead of koro. . .’

Watch Footsteps of Sound.

- Rehearsals for Revolution at Serendipity Art Festival, 2024

- Her Voices at ‘Like Air, I’ll Rise’, Experimenter, 2024

- Baba Betar at Chobi Mela Shunyo 2021

- A Slightly Curving Place 2020

- Chobi Mela Biennale, 2019

- Time upon Time: Arnold Bake in Bengal 2016

- Baul Fakir Utsav 2006-2015

- Travelling Archive in East London 2015

- Unbox 2013

- Life of Rivers, 2011